|

|

||

|

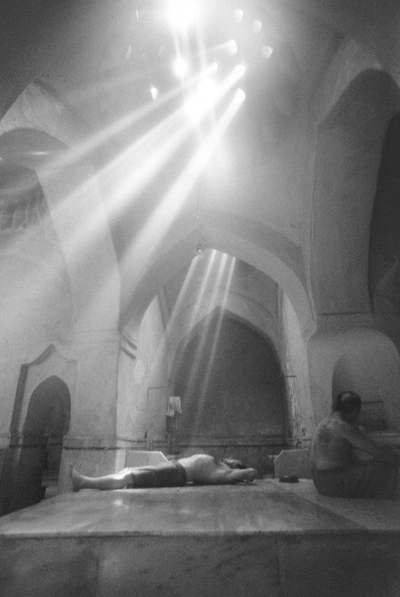

Roca London Gallery’s new show plunges into the long, steamy history of public bathing. Curator Jane Withers tells us more Ever since I can remember I’ve been obsessed with bathing and bathhouses. The Roman empire came alive through intricate 19th-century prints of the baths of Caracalla and Diocletian – impossibly grand marble halls teeming with athletes and slaves, senators and thieves. Federico Fellini’s 8½ made me long for the twilight of the spa town where the fatally languid Marcello Mastroianni seeks rejuvenation through spring waters and finds Claudia Cardinale. Since then I’ve become what the Japanese describe as an ofuroholic (one addicted to the ‘furo’ or hot bath), whenever possible bathing in the remnants of great water cultures, from a former Roman bath off-grid in rural Tunisia to Moscow’s great Sandunovsky baths, where the

Soak Steam Dream: Reinventing Bathing Culture at Roca London Gallery explores how a renewed interest in this historical panorama is leading to a rediscovery of bathhouses as community spaces. Unlike spas today – almost invariably places of privilege and luxury – the bathhouse has inclusive roots. It is a place of synthesis and reconciliation, and even of vulnerability, where our urban defences are discarded along with our clothes, and antagonism melts in the steam. Finnish architect and sauna enthusiast Tuomas Toivonen even describes its architecture as ‘a space of anti-conflict, anti-competition and anti-hierarchy’. If you take the long view of bathing culture, the later 20th-century looks like the dark, dry ages, the nadir for most ancient and sociable water rituals – the rise of the private bathroom has eclipsed communal bathing in the West, with fear of depravity hastening its decline. Already, in Mechanization Takes Command (1948), Sigfried Giedion bemoaned the arrival of the modern bathroom, lamenting that the great Roman bathhouse had been replaced by a prison cell. In his influential study The Bathroom (1966), Alexander Kira reduced bathroom design to a study of hygiene and ergonomic efficiency – modern sanitation massively improved public health at the cost of both a great architectural tradition and our natural connection to water. In H2O and the Waters of Forgetfulness (1985), Ivan Illich described how industrialisation distanced us from water: ‘In the imagination of the 20th century, water lost both its power to communicate by touch, its deep-seated purity and its mystical power to wash off spiritual blemish. It has become an industrial and technical detergent.’

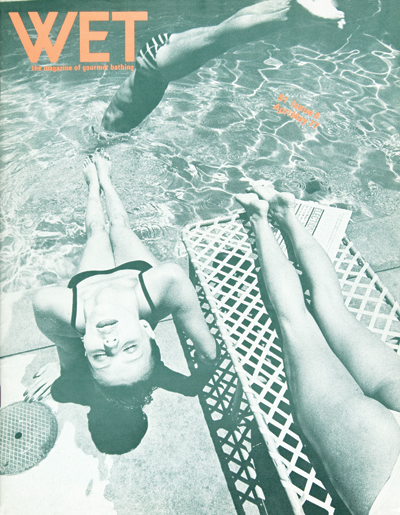

But, in the 1970s, resistance gathered momentum – artist and bathing aficionado Leonard Koren founded Wet: The Magazine of Gourmet Bathing (1976–81), a publication as original and absurdist as its title, with articles on mud baths alongside works by Matt Groening and April Greiman. Later, Koren published Undesigning the Bath (1996), where he promoted the idea that bathing is as much a state of being as an act of cleansing: ‘How do I define a great bathing environment? … [A] place that awakens me to my intrinsic earthy, sensual and paganly reverential nature.’ Built over natural hot springs using local quartzite rock, Peter Zumthor’s majestic Therme Vals (1996) provides a framework for an elaborate choreography of bathing rituals and water experiences that reconnect us to the ancient meaning of spa (‘salus per aqua’, or ‘healing through water’).

Today, new bathhouse models are emerging in response to changing social and urban conditions and shifting boundaries between public and private space. Raumlabor’s Gothenburg sauna – a community project in a disused container port – is in part a catalyst for regeneration. The gawky corrugated-iron structure towering over shipping containers and naked bathers creates a powerful image of change. Barking Bathhouse, a temporary project by Something & Son for the 2012 London Olympics, referenced the work of 19th-century social activists in establishing over 100 public baths for the poor, some of which remain today, most dolled up as spas. A few have survived intact, however, including west London’s Porchester Baths, with its great tiled steam rooms and whip-wielding ‘Schmeissers’. Perhaps, in our increasingly water-stressed and overcrowded cities, such sociable institutions are finally beginning to make sense again. |

Words Jane Withers |

|

|

||

|

|

||