Designed by Bjarke Ingels Group and Kilo Design for Virgin Hyperloop, the pod hosted the world-first passenger ride on the innovative transport mode

Words by Francesca Perry

Along with most of Elon Musk’s ventures, Hyperloop may have become a punchline; shorthand for overly ambitious, essentially fantastical transport projects. It promises a lot – the fastest-ever ground transportation, a sustainable alternative to air travel – but carries its share of problematic baggage: costs, feasibility and safety, to name a few.

But what once seemed pie-in-the-sky when Musk first raised the idea eight years ago is slowly coming to some kind of fruition. This November, the world’s first passenger ride took place on an innovative high-speed levitating pod system designed by Danish firms Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG) and Kilo Design for Virgin Hyperloop.

The Hyperloop concept centres on a sealed tube or system of tubes with low air pressure through which pods engineered with magnetic levitation can travel substantially free of friction, thus enabling extremely high speeds.

Though the system was initially proposed for the US stretch between the Californian cities of San Francisco and Los Angeles, the high-speed transportation – the design of which has been open-sourced – has since been suggested for routes all over the world, including Helsinki to Stockholm in Scandinavia, Edinburgh to London in the UK, and Mumbai to Pune in India.

Virgin Hyperloop (formerly Hyperloop One) was established in 2014 to develop the Hyperloop concept. By 2017, it had completed a 500m-long Development Loop (DevLoop) site outside Las Vegas, Nevada, and performed its first full-scale Hyperloop test. In 2019, Virgin Hyperloop partnered with BIG and Kilo to design Pegasus, a new vehicle typology for an autonomous transportation system to achieve Hyperloop travel.

The passenger ride test this November at the Nevada DevLoop site was the company’s first, following over 400 tests in un-occupied pods. ‘When we started in a garage over six years ago, it felt like a distant dream to one day ride in a Hyperloop pod,’ said Josh Giegel, Virgin Hyperloop co-founder and CTO, who was one of the passengers on the test. ‘Today, that dream came true.’

The pod reached speeds of 172kmph (107mph) on the 500m-long, 15-second journey; it’s worth noting, however, this is a long way off Virgin Hyperloop’s goal of achieving speeds of more than 1,000kmph.

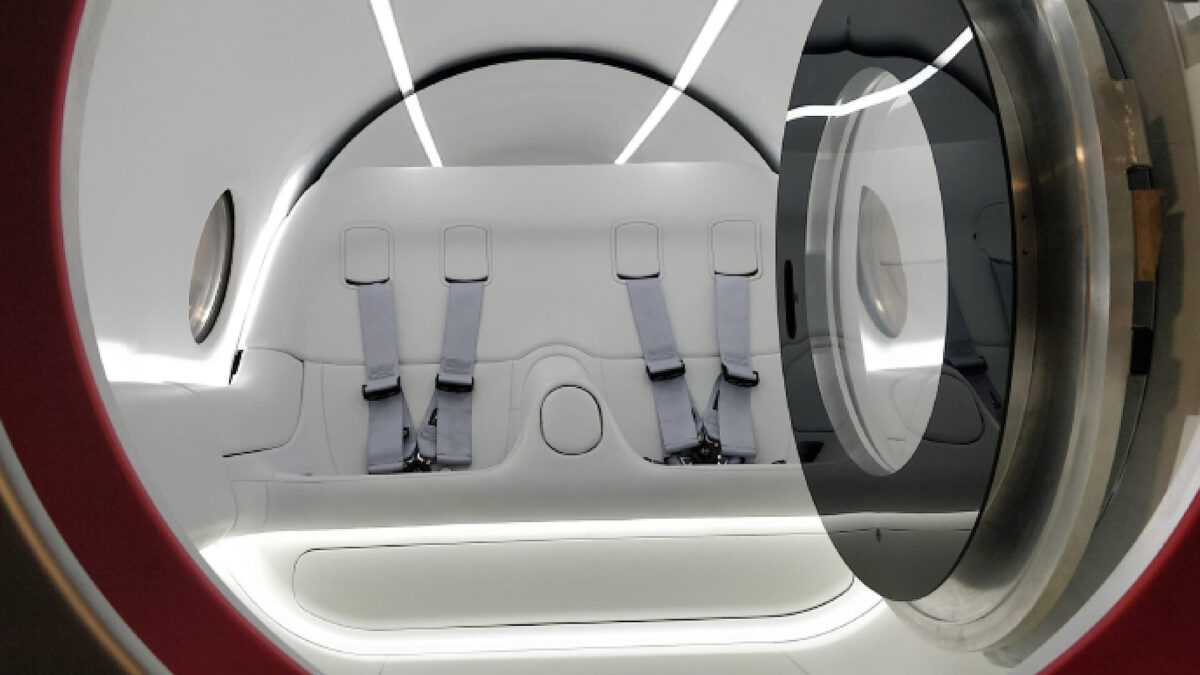

The two-seater, 12 sq m Pegasus pod was conceived as a pressurised vessel; the design focuses on unifying and covering both the pressure vessel and sled, creating as seamless an appearance as possible.

Since Hyperloop travel exists in a near airless tube, the design did not have to accommodate aerodynamic features. The front ‘scoops’ of the vessel create steps for entry and exit, and a forward-facing window embedded in the access door enables outward viewing down the tunnel. (Do the pictures make it look like a sexy and well-lit washing machine? Maybe.)

Externally, repeating soft forms and pill-shape cut-outs are used to highlight depth, layers and entryways. Inside, the seating elements and extended arms serve multiple functions including as an entry and exit aid, and as storage for safety equipment and lighting.

‘When designing the future of transportation and the slate is sort of blank, the opportunities are endless,’ says Jakob Lange, partner at BIG. ‘We’ve needed to adjust our way of thinking away from the classic modes of transporting like trains, planes and metros, and towards a new vehicle typology, closest to that of a spaceship.’

Bjarke Ingels, BIG founder, adds: ‘Virgin Hyperloop with our Pegasus pods changes the experience of moving across a country or even a continent into that of a subway system – one that could eventually cover the entire globe and push global travel into a more sustainable direction.’

BIG has also worked with Virgin Hyperloop to design a Hyperloop Certification Center (HCC), which is due to be built in West Virginia.

Of course, Virgin isn’t the only one in the game and plenty of other companies around the world are developing their own Hyperloop technologies. Actually getting Hyperloops built, however, requires land, myriad regulatory resolutions, time, resources and critically, huge sums of money.

By numerous estimates, the opening of a functioning Hyperloop system is still many years away – the UK’s Department for Transport has said it would take ‘decades’ to achieve – and we may just get to Mars first.

Imagery courtesy of Virgin Hyperloop