|

It’s difficult to think of the High Line without thinking of Joel Sternfeld’s photographs of it in different seasons at the turn of this century. It’s difficult to think of the High Line without thinking of Joel Sternfeld’s photographs of it in different seasons at the turn of this century. You can’t see them without wanting to be there – and be there alone. Like a ribbon of prairie running through Manhattan, the overgrown elevated railway had a melancholic beauty which was all the more poignant for being inaccessible. Sternfeld managed to make it feel like the only place where you could simultaneously be in New York while getting New York out of your system. But the High Line as it was then was a forgotten place, a freak landscape, an anomaly. There is no place for any of those things in today’s Manhattan. And, in this case, rightly so. After a decade’s worth of campaigning, wrangling, arm-twisting and designing, the High Line has finally opened to the public. This is only the first phase of what will eventually be a one-and-a-half mile long park on stilts, but it now takes you nine blocks from Gansevoort Street in the Meatpacking District up to 20th Street in Chelsea. Designed by landscape architect Field Operations and architect Diller, Scofidio & Renfro, it is, I believe, the finest recent urban park in the world. Why? For the simple reason that this is a park with the opportunity to be not just about itself but about the city around it. At least half of its pleasure is voyeuristic. There’s the thrill you always get from going on someone’s roof and gaining a new aspect on the metropolis, except here you’re not limited to a few square metres, you can walk for half a mile. You can look up, down, into someone’s window, out to the Hudson River. It’s like a tiny sliver of Constant’s New Babylon or Yona Friedman’s La Ville Spatiale, or any of those other Sixties visions of a tiered city – only it comes not courtesy of the latest in urban planning but thanks to a redundant piece of 1930s infrastructure. The High Line opened in 1934, running alongside 10th Avenue and passing straight through the warehouses on the west side of Manhattan, delivering meat and other foodstuffs. It became less useful when trucking took over as the delivery means of choice in the 1950s, and finally saw its last train run in 1980. It has been derelict ever since. The former mayor of New York, Rudolph Giuliani, actually signed off its demolition, and it is to the credit of his successor, Michael Bloomberg – who is often criticised for being a developers’ mayor – that he reversed that decision. Most of the credit, however, goes to Joshua David and Robert Hammond, who set up Friends of the High Line in 1999 and campaigned for it to be converted into a park until 2004, when the current designers were picked out of a competition with 720 entries. The architecture of the High Line itself has always been compelling. It’s like an exposed flank of skyscraper structure lain on its side. A tickertape of rivets, those little emblems of New York’s early thrusts at the sky. That structure remains largely untouched. You gain access to it from five simple stairs between Gansevoort and 20th Streets. When you get on the upper side, the landscaping is restrained and feels pleasingly like an overgrown railway, except with a promenade woven through it. The tracks remain exposed here and there, sown with wild perennial flowers and grasses by the Dutch planting designer Piet Oudolf. This meadow flora is cut through with a railway-like vocabulary of rusted steel planters and concrete finger slabs that rise up into wooden-slat benches. Everything is thin – the benches are only 12 inches wide – as befits this hyper-narrow park. Its concentration is its strength, along with its restraint. You are not overwhelmed by design, by distracting features. The rhythm is consistent and easy as you follow the meandering and forking promenade. As James Corner, the head of Field Operations, says, “It’s about the accrual of experience through walking rather than any one place.”

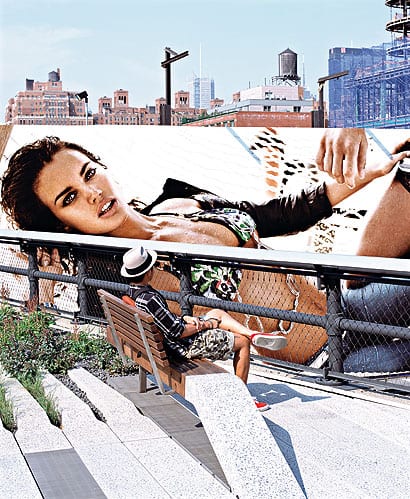

The beginning of the High Line, at Gansevoort Street There are definitely moments, however, that encourage you to pause. One occurs where the track branches off and hits a dead end at a yellow brick wall that once it would have passed straight through. Another is the so-called 10th Avenue Square. Here you can see the hand of Diller Scofidio & Renfro, re-using a trick that will be familiar to those who’ve seen its media room at the Boston ICA (the only high point of that building). As it did in Boston, the architect has cut steps into the structure descending towards a spectacular view – only this time it looks out at 10th Avenue, not the sea. The square is part lunch spot and part urban cinema. There is drama in that vista, even if you don’t know that 10th Avenue used to be called Death Avenue because of all the accidents – the very reason why the goods trains were elevated in the first place. Let’s hope it’s not a Tarantino lunch break. The beauty of the High Line is that it makes a stage of the city. You overlook the streets as from the peanut gallery. But there are other, stranger privileges of strolling along at this level. You can look into the windows of Phillips de Pury auctioneers, and peer into junk-filled back yards. You pass so close to an Armani billboard that you can examine the grain on the water droplets clinging to the model’s skin as she tugs the pants off a disembodied male torso. There’s something illicit about these vantage points. The High Line also now connects two neighbourhoods, the Meatpacking District and Chelsea, each with similar trajectories. As it stands, the Meatpacking District is schizophrenic, with the High Line bisecting its two identities. To the east is the chichi world of Alexander McQueen boutiques and Pastis bistros, not to mention Manhattan’s hippest new hotel, The Standard, which straddles the railway like an unusually stylish 1960s office block. To the west is what’s left of the meatpackers. I asked Amanda Burden, chair of the New York Planning Commission, whether the High Line was the final nail in the coffin of this local industry and she claimed not. The zoning, she argued, remains commercial and light industrial, but it’s hard to imagine how Quality Veal Corp will survive when Renzo Piano’s new Whitney Museum pops up next door. Off to the Bronx with it, perhaps, where a new food market beckons. The fact is that your average New Yorker can’t afford either to eat or shop in the Meatpacking District. But anyone can enjoy the High Line. And they wasted no time. Before the opening press conference had even broken up there were joggers bouncing past the camera crews and a pair of newlyweds posing for their wedding portraits. Although the High Line has an obvious precedent in the Promenade Plantée, another former elevated railway in Paris converted in the 1990s, it is actually much closer in spirit to the roof of Foreign Office Architects’ Yokohama Ferry Terminal. That is the only raised public space I’ve experienced that prompts the same kind of spontaneous and dynamic appreciation. As it stands, the High Line is already a wonderful asset for New York, and this is only phase one. Another ten blocks of landscaping is scheduled to open some time next year, with the final installment around the West Side rail yards coming thereafter. For now, when you meet a rude wire fence at 20th Street, you find yourself looking longingly down the rest of the line.

Timber sun loungers on the tracks

The concrete-beam promenade meanders down the line

A promenade among the billboards. Concrete pavers rise up to become benches

Plan: James Corner Field Operations and Diller Scofidio & Renfro. Courtesy of the City of New York

One branch of track, sown with wild flowers, hits a brick wall |

Image Floto+Warner

Words Justin McGuirk |

|

|

||

|

After passing through the Chelsea Market building, the High Line forks |

||