|

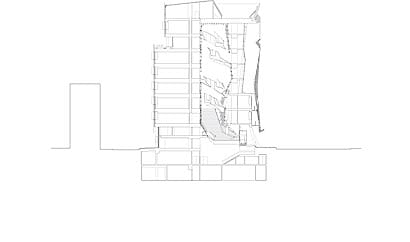

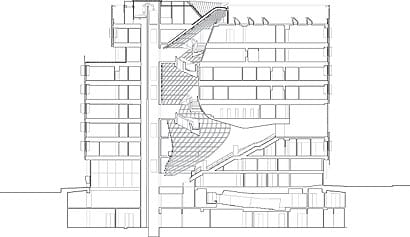

Landing in Manhattan after a spate of self-obsessed shininess and delicacy, Thom Mayne’s raw, audacious academic building for the Advancement of Science and Art delivers a much needed punch in the city’s architectural face. It starts at the facade. The perforated metal skin that hangs loose around the blocky, nine-storey concrete envelope hints at excess and inaccessibility, like a shimmering gown or the plate armour of a rhinoceros. But at the centre it suddenly bends and tears open towards a bustling interior atrium that branches out into laboratories and classrooms and burrows up to a rooftop skylight. At ground level, the scrim lifts to usher the public into a luminous lobby that overlooks a sunlit gallery. It’s a sensuous culmination of the rough-edged experiments Mayne’s firm Morphosis has pioneered in California, turning the guarded mentalities of the academy and New York on their heads. Such tough love is welcome in a neighbourhood where architectural novelty has recently meant mediocrity. Once the birthplace of New York punk, this corner of the East Village has in the past half decade ceded to a gentrification best exemplified by a pair of predictably curvy glass-and-steel towers by Charles Gwathmey and Carlos Zapata. Just up the street, St Mark’s Place is more tourist draw than transvestite drag, and the rock music landmark CBGBs is now a high-end fashion boutique. In this context, the building, at 41 Cooper Square, struts onto the scene looking both radically new and refreshingly familiar, updating punk brawn with a heavy dose of brain. The perforated facade, which cuts solar radiation during the summer and insulates in cold weather, features panels that swing open to let light in and keep heat out as needed. Mayne inaugurated this system on the skins of the Los Angeles headquarters for Caltrans District 7 and the San Francisco Federal Building, which are in many ways this building’s antecedents. But Mayne’s focus on the texture of the second skin, along with its swooping shape, gives the structure a more delicate touch than usual, partly foreshadowing the sensuality of the 68-story La Phare tower Mayne is building in Paris. At moments, the perforated facade can echo the matte finish of SANAA’s New Museum, just a few blocks south. From other angles, the exterior gives off a shimmer. At night, interior lights transform the building into a cubist lantern. On top of this sexy glass-steel-and-concrete dress, the facade sprouts a wardrobe malfunction: a gash of glass that cuts across the ninth floor and down through a wide central slot. Where the apertures in the brash exterior of Caltrans double as billboard-style lettering, the gash at Cooper Union comes off as something more cryptic, like wild Chinese calligraphy. But this isn’t mere bravura. It’s a window into the building’s heart, a white, sky-lit hive of an atrium that rises from basement to roof, crossed by small bridge stairways and buzzing with the movement of the city. “The street becomes the facade and as you enter it the inside becomes the street,” says Mayne. Next to this muscular and sophisticated exterior, the smooth contours of Zapata’s newly opened Cooper Square Hotel, just next door, look even more out of place, like a miniature version of an obnoxious Dubai tower, or a puffed-out chest. Mayne says he was conscious of making a building that screamed for New Yorkers’ attention. “At some point I felt some pressure and a huge opportunity as an outsider to build a building that was an iconic kind of presence,” he says.

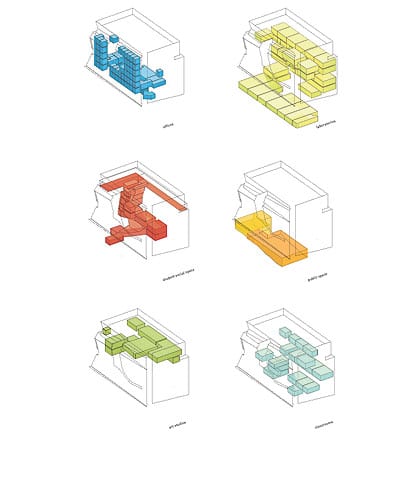

Mayne hopes his curving staircase will provide students with a “vertical campus” meeting space But the building is less concerned with one-upmanship than with celebrating the excitement of its own making, and sharing that exuberance with the neighbourhood. The building encourages passers-by to peek under its steel dress and check out its window wall, to step inside the lobby, or simply to gaze up along the swoop of the scrim, a nod to the Mansard roofs of the 19th-century Parisian townhouse across the street. A large, angular glass cut-out on the rear facade also turns attentions outward, reflecting the dome of the Ukrainian Catholic Church just behind the building. The structure makes overtures to its great-grandfather, the 1859 Cooper Union Foundation building across the street. The new building, opening on the school’s 150th anniversary, mimics the scale and shape of the old Italianate edifice. Mayne has also oriented the lobby toward the old building’s entrance, designed an eighth-floor terrace to match one on the older building, and included a below-grade theatre that hints at the foundation’s Great Hall, which has hosted leaders from Lincoln to Obama. But next to the elder statesman, Mayne’s thick concrete columns slide down at angles under the metal exterior like the hairy legs of a cross-dresser. From the cracks in its concrete slabs to the building’s gestures toward transparency, the building eschews refinement for an eye-opening approach which fits the school’s larger mission. To Mayne’s delight, the project confronted him with two challenges more pronounced than usual: money and space. The building was on a tight budget – $150 million – that Cooper Union had to raise mainly from its alumni. And Morphosis would need to make wise use of space: in the transition to the new building from a nearby laboratory centre that Cooper Union plans to develop for commercial use, the school is losing 40,000sq ft of usable space. From an initial slate of 150 nominees, Morphosis won the commission on the strength of, among other things, an attention to value. It’s an asset born out of Mayne’s experience with schools and government buildings, and learned in concert with other Angeleno architects, like Frank Gehry. “I started making material-laden, detail-laden work. But the concentration on the making process was no longer tenable. Some of the results are definitely manifest in the building,” he says, referring to its raw, unfinished quality. “It’s a limit I’ve learned to use.” The building’s translucent qualities lend it an atmosphere of liveliness and activity To maximise space, Morphosis built as much volume as zoning rules would allow, and placed an emphasis on multi-use spaces, governed by more efficient scheduling. How well this approach fares under the weight of the student population remains to be seen when the building opens in September. But a bigger test awaits a riskier solution to tight budgets and even tighter space: “skip-stop” lifts that only stop on the fifth and eighth floors. Instead, Mayne makes the stairs fun, a bid to intensify circulation, build social connections and, yes, encourage exercise. The grand, curving staircase that leads from the lobby to the third floor is meant to be a meeting point; look up and the cavernous atrium reveals jagged stairways criss-crossing the space, each leading to mezzanines placed near the facade’s glass opening. To underscore the feeling of a “vertical campus,” Morphosis has enveloped the atrium with a web of white gypsum that rises from the lobby to the skylight. “I like the notion of connectivity, the opportunities for connectivity it produces in public space,” says Mayne of the stair-heavy approach, which he has already put to use at the San Francisco Federal Building, a dormitory for graduate students at the University of Toronto, and Caltrans. “In this building, we’re working with something much more random; each stair had its own characteristic. We wanted to bring the complexity of the city into the building.” But the building’s coup de grâce is also its biggest liability. At Renzo Piano’s New York Times building, which also evinces a love for transparency, the stairs are placed up front, along the windows, to encourage users to walk between floors. But that building, refined compared with 41 Cooper Union, also includes a high-speed elevator system. Standing in the Mayne’s empty atrium, one can already hear an echo of groans. He mentions some protests (there have also been talk of lawsuits by handicapped groups), and complains about a critic that didn’t grasp the idea. But even if skip-stop lifts are a bizarre novelty now (they were pioneered by Soviet constructivist Moisei Ginzburg in the 1920s), Mayne likens them to a car’s seat belt or cup holder, innovations that have now become standard. If Mayne is Zen about the opposition he faces, it’s not because his success makes him impervious to criticism. Rather, Mayne says he has no choice but to make buildings that solve problems and raise questions too. The building’s approach to efficiency and community may spark complaint, but it will also provoke conversation. “It’s not about whether you like it or dislike it,” Mayne says. “Architecture needs to alter the way we think about the world and the way we behave. The litmus test of any serious architecture has to be that.”

|

Image Iwan Baan

Words Alex Pasternack |

|

|

||

|

The Cooper Union contrasts with the bulges of Carlos Zapata’s new Cooper Square hotel, far right |

||