The 2018 Pritzker Architecture Prize winner was one of India’s most influential architects, celebrated for his humanist philosophy and sustainable approach to architecture

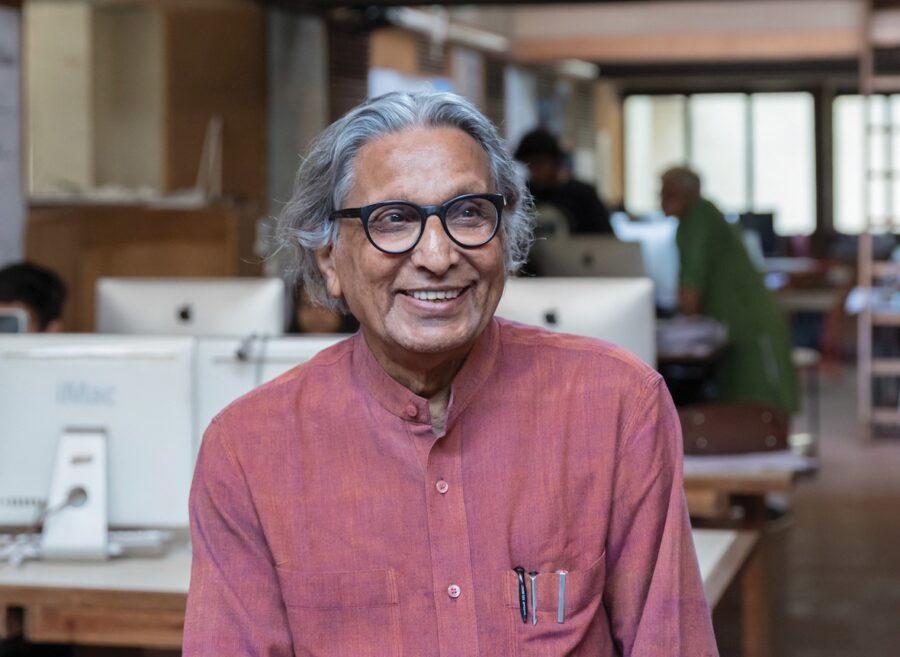

Photography by Iwan Baan, 2018, featuring Balkrishna Doshi at Sangath Architect’s Studio, Ahmedabad, 1980. As seen at Balkrishna Doshi: Architecture for the People, Vitra Design Museum, 2019

Photography by Iwan Baan, 2018, featuring Balkrishna Doshi at Sangath Architect’s Studio, Ahmedabad, 1980. As seen at Balkrishna Doshi: Architecture for the People, Vitra Design Museum, 2019

Interview by Priya Khanchandani

In 2018, Balakrishna Vithaldas Doshi became the first Indian architect to win the Pritzker Prize. His extensive career spans huge political and economic changes: the period of India’s independence, the liberalisation of India’s economy and the growth of a new middle class.

Doshi started out with a stint working with Le Corbusier in Paris before setting up his own practice in Ahmedabad, north-west India, where he designed the iconic modernist campus of the Centre for Environment and Planning Technology (CEPT), which was completed in 1972.

In ICON 184, Doshi spoke to Priya Khanchandani about his most memorable works – including the Aranya low-cost housing development in Indore, which was awarded an Aga Khan Award for Architecture – while reflecting on how architecture could help India’s poor.

To honour Balkrishna V. Doshi, who died aged 95 on 24 January 2023, and his valuable contribution to the evolution of architectural discourse in India, we’re republishing the full interview from the ICON archives.

Photography by Vinay Panjwani featuring Lalbhai Dalpatbhai Institute of Indology, Ahmedabad, 1962. As seen at Balkrishna Doshi: Architecture for the People, Vitra Design Museum, 2019

Photography by Vinay Panjwani featuring Lalbhai Dalpatbhai Institute of Indology, Ahmedabad, 1962. As seen at Balkrishna Doshi: Architecture for the People, Vitra Design Museum, 2019

ICON: You were born before India’s independence. How have you seen architecture in India change?

BV DOSHI: Most of the architects who were practising then were members of the Royal Institution of British Architects in London. When I joined the Sir JJ School of Architecture in Mumbai in 1947, I saw many buildings by Indian architects, and they were trying to connect the Western colonial style along with Indian elements.

I was impressed by the way the people were trying to Indianise European architecture by adding human figures to buildings, as well as traditional Indian features such as overhangs and domes and chhatris. Those features became the corrective fix of noble Indian architecture.

ICON: How did you see that change after independence?

BVD: Well, it did not change for, let’s say, another ten or 15 years, but then young architects came from Western countries like England or the USA. And when they came, they started talking about a different approach and some of them began to think about the climate and hybridisation between an Indian expression and the Western view.

ICON: And then of course, there’s your style of architecture, which melds a kind of modernism with a unique Indian aesthetic.

BVD: Well actually, then came Le Corbusier. When he came to India, he began to look first of all not at technology or anything, but at what could be the contemporary approach to looking at architecture. He looked at Indian architecture, Islamic architecture, Mughal architecture, he saw where there were verandas, and then there were all these canvases which had protections for shade.

He looked at those things. He saw the open plan, the free plan. He looked at the breeze, he looked at the sun, he looked at humidity. So, the question was now one of looking at climate, culture, technology, and sustainability. This is how he began to express his work, completely different to what other people were thinking. So, then I began to think about how I could go beyond what Corbusier had done. This is how I started to change and look at Indian work in a different way.

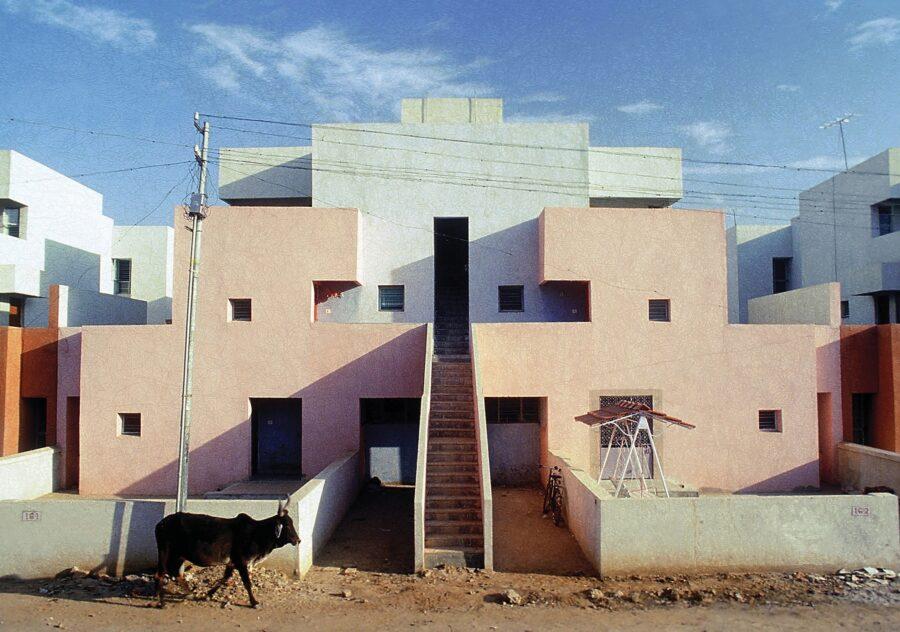

Photography courtesy of Vastushilpa Foundation, Ahmedabad featuring Balkrishna Doshi, Aranya Low Cost Housing, Indore, 1989. As seen at Balkrishna Doshi: Architecture for the People, Vitra Design Museum, 2019

Photography courtesy of Vastushilpa Foundation, Ahmedabad featuring Balkrishna Doshi, Aranya Low Cost Housing, Indore, 1989. As seen at Balkrishna Doshi: Architecture for the People, Vitra Design Museum, 2019

ICON: After working with Le Corbusier, you set up your own practice. How did that come about?

BVD: Well, I always wanted to be on my own. When I was 24, I came to Ahmedabad. There, I knew no one. I was a new person. And I came there without any financial resource. So, the only way was to start my own practice.

ICON: What kinds of project did you work on at the outset?

BVD: I began with some housing for the staff at the ATIRA textile institute – low- cost, one-room housing. Then, I was commissioned to design a Montessori school, which was an interesting job because it had to consider both the institutional building and its ethos of learning from nature.

So I devised sliding windows, to deflect the sunlight. It taught me a lot about how to exploit rainwater, how to bottle the temperature of the sun, and how to create ventilation using shade. It was a huge learning experience, and allowed me to move on from Corbusier.

ICON: Which other projects stick in your mind as being the most memorable?

BVD: The ATIRA project was interesting. It had big arches, big walls, and I even had to manufacture these metal louvres because people couldn’t afford glass. It taught me how to create comfort with the minimum amount of material.

This project has stuck in my mind: even today, I try to find ways to minimise accessories. My own house, for instance, which was built in 1959-60, has no glass windows. Everything is made of wood and then there are overhangs which give me indirect light.

So, cross-ventilation became important. Maintenance became important: can you reduce maintenance? Can you reduce dust? Can you find the right level of comfort? And when your house is closed as if it’s a box, can you create a sense of light? I learned about how to achieve these things.

Photography courtesy of Vastushilpa Foundation, Ahmedabad featuring Balkrishna Doshi, Housing for the Life Insurance Corporation of India, Ahmedabad, 1973. As seen at Balkrishna Doshi: Architecture for the People, Vitra Design Museum, 2019

Photography courtesy of Vastushilpa Foundation, Ahmedabad featuring Balkrishna Doshi, Housing for the Life Insurance Corporation of India, Ahmedabad, 1973. As seen at Balkrishna Doshi: Architecture for the People, Vitra Design Museum, 2019

ICON: And are these principles that carry through to your most famous works?

BVD: Yes, even today, I follow them. The other lesson was our traditions of architecture: how they created verandas, how they created ventilation, and I tried to reinterpret that in a new vocabulary.

ICON: The CEPT in Ahmedabad is often seen as one of your major triumphs. Can you tell me your thinking around that?

BVD: I began to teach at Washington University in St Louis, USA. That was in 1958. I realised that students need freedom and informality, as well as a connection between the outdoor and indoor. I started thinking about an institution without boundaries, without doors.

For the site, I selected a wasteland that already had a brick hill and burned earth. So, I tried to transform that into a landscape, and integrated this eroding landscape into the CEPT campus. Transformation is very important for me. Transformation of existing situations, circumstantial situations, and creating something that makes you feel completely changed – and delighted.

ICON: The principles that you talk about – for example natural light, natural ventilation, not having glass – seem to be the antithesis of much contemporary South Asian architecture. Would you agree?

BVD: I think there are certain questions we need to start with when building in this environment. Are we ready to save energy? Are we ready to save on maintenance? And without using mechanical or technological devices, could we be comfortable like our ancestors were and still achieve a contemporary expression?

Photography courtesy of Vastushilpa Foundation, Ahmedabad featuring Kamala House, Ahmedabad, 1963, 1986. As seen at Balkrishna Doshi: Architecture for the People, Vitra Design Museum, 2019

Photography courtesy of Vastushilpa Foundation, Ahmedabad featuring Kamala House, Ahmedabad, 1963, 1986. As seen at Balkrishna Doshi: Architecture for the People, Vitra Design Museum, 2019

ICON: What do you think the answer is?

BVD: A contemporary expression is the free flow of spaces, modulation of spaces, modulation of light, modulation of volume. And this is what I have tried to achieve.

ICON: Do you think contemporary architecture does justice to the local climate, materials and context of India?

BVD: I don’t think so. These days, everyone is exposed to affluence. The client today is more affluent than before. And less conscious of economies of scale.

ICON: What are you working on today, in this changed environment?

BVD: We are creating institutions based on zero principles. That means that we use absolutely minimum energy to live or to work.

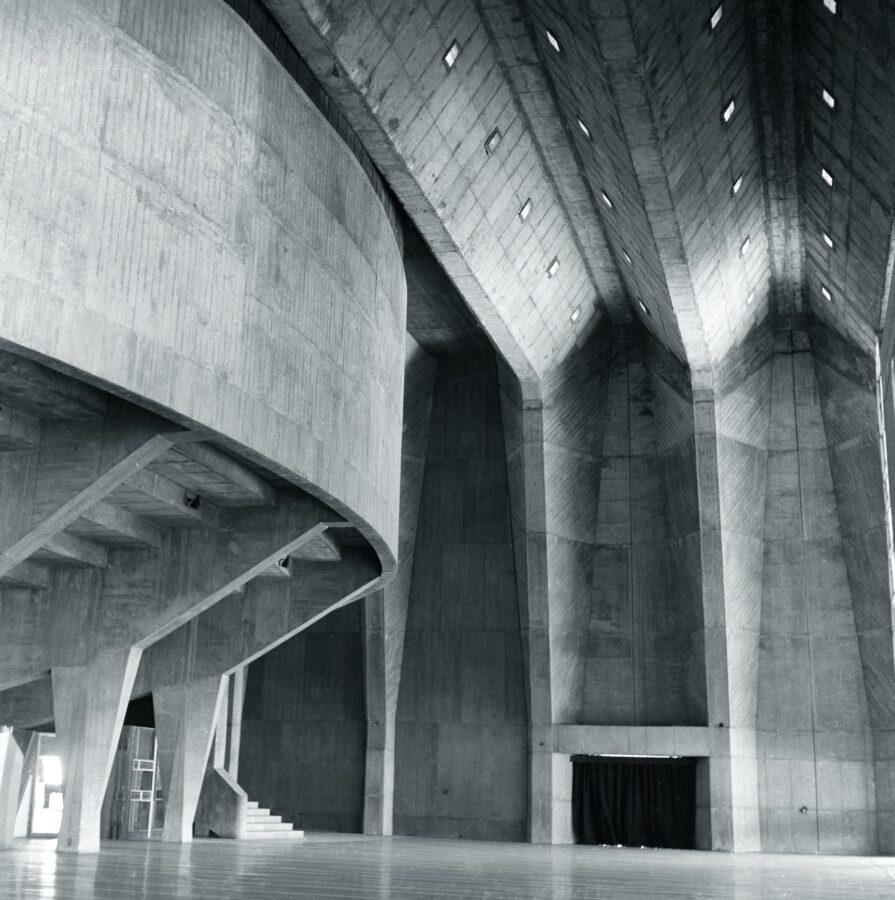

Photography courtesy of Vastushilpa Foundation, Ahmedabad featuring Tagore Memorial Hall, Ahmedabad, 1967. As seen at Balkrishna Doshi: Architecture for the People, Vitra Design Museum, 2019

Photography courtesy of Vastushilpa Foundation, Ahmedabad featuring Tagore Memorial Hall, Ahmedabad, 1967. As seen at Balkrishna Doshi: Architecture for the People, Vitra Design Museum, 2019

ICON: Do you think architecture can provide solutions to India’s inequality?

BVD: The architect today is usually concerned about people who have resources. But India has another half, which does not. Can they be empowered to really do something for themselves?

What they often don’t have is a piece of land and ownership of that land. I proposed a scheme in the 1980s, in Aranya, Indore. We were given [a plot] of land by the government.

ICON: I see. What did you do with it?

BVD: Using a lottery system, we gave each family a small plot with only a water tap, toilet and electric connection and we said: you build a house of your own. The moment you gave them ownership, they became secure that they had a place where, eventually, they could dream of a house.

If one goes there today, they have built their own houses. Not only that, but they have added a floor so then they can sublet it, use the money to educate their children and get better facilities in their house. And slowly that community of 40,000 people has grown to at least 80,000.