|

|

||

|

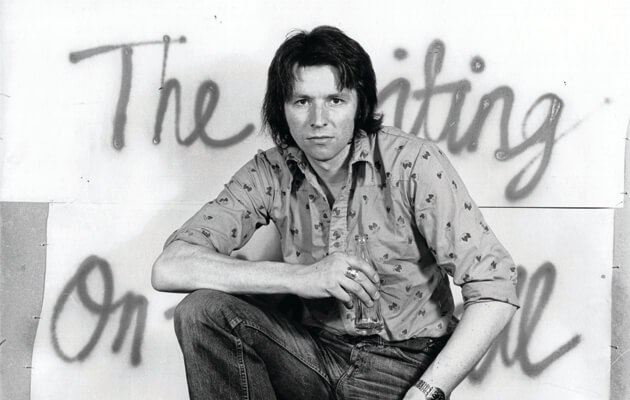

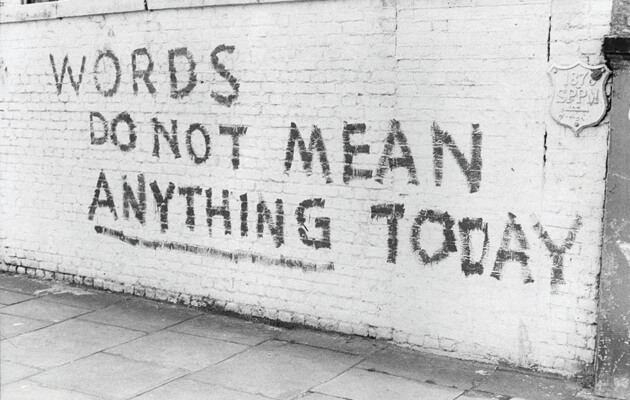

Roger Perry’s photographs of graffiti in 1970s London showed wit, surrealism and anger scrawled across an age of austerity. Sukhdev Sandhu welcomes their reissue When it was published in 1974, The Faith of Graffiti – with photos by Mervyn Kurlansky and Jon Naar – was immediately hailed as an important treatise on the modern city. Its images of New York subway carriages adorned with vivid tags and spray-can art were accompanied by a lengthy essay by Norman Mailer, who saw graffiti as “the expression of tropical peoples living in a monotonous iron-gray and dull brown brick environment”. These people, he claimed, were trying “to save the sensuous flesh of their inheritance from a macadamization of the psyche”. Less well known is The Writing On The Wall, a 1976 volume designed by Pearce Marchbank that collected Time Out and Sunday Times photographer Roger Perry’s images of the slogans, riddles, insults and urban poetry painted across London. Like New York, the English capital was struggling with recession, white flight and housing shortages. And, like Mailer, the jazz singer and surrealist George Melly, who penned the introduction to Perry’s book, saw graffiti as an exercise in collective liberation: “In a world of supermarkets, office-blocks, processed chickens, VAT forms, computers, ECT, time and motion studies, what graffiti proclaims is ‘Human beings rule OK!’” The Writing On The Wall is back in print thanks to a Kickstarter campaign organised by London-based artist, curator and self-professed “dilettante” George Stewart-Lockhart. It is a handsome reissue that’s supplemented by previously unpublished archive shots, fond reminiscences of Perry by friends and colleagues such as former Granta editor Ian Jack, and an essay by the KLF’s Bill Drummond that likens graffiti to schoolboys pissing on walls. Stewart-Lockhart himself contributes an excellent foreword in which he talks to some of the authors of these previously unattributed slogans and tags – they include Whale Nation poet Heathcote Williams and Lee Thompson and Mike Barson from the band Madness. The newer writers make a point of not calling the graffiti “street art”, a label they regard as tarnished by the modern vogue in which estate agents, boutique hotels and advertisers profit from and defang a formerly verboten form of metropolitan calligraphy. Compared with the messages inscribed across London today, those in Perry’s book are visually rather austere – more textual than graphic. They’re also more political. Overcome Apathy; Eat The Rich; Fight Back: the walls vibrate with energy, almost goading pedestrians to be agitated. Not all are left wing; some salute the National Front and the British Union of Fascists leader Oswald Mosley. Others are charmingly polite (Stop War Please), misspelled (Release The Shewbury Three), or as precise as an activist press release (250 People With 30 Kids Face GLC Eviction And Demolition Threat). Graffiti is usually seen as ephemeral, as analogue-era Snapchat. Some slogans, especially in hard-to-access nooks, lingered like strange perfumes for months and sometimes years. One can only imagine the wonder, befuddlement or quotidian surrealism experienced by Londoners who regularly passed by graffiti such as Beware The Thundrous Trowel Surgeons; Remember The Truth Dentist; Princess Anne Is Already Married To Valerie Singleton; or (my personal favourite) How Much Longer Must Our Lives be Dominated By Prussian Horse Cripplers, A Puerile Debating Society and Nebbisches from Cobweb Corner. On occasion, inspirations or influences can be traced. The Tigers Of Wrath Are Wiser Than The Horses Of Instruction is a direct lift from the poet Shelley. The situationist-inspired Same Thing Day After Day – Tube – Work – Dinner – Work – Tube –Armchair – TV – Sleep – Tube – Work – How Much More Can You Take is said to have prompted the lyrics of Time by Pink Floyd. This kind of witty, inflamed creativity in the face of austerity resonates with today’s equally depressed climate. And the dour, blitzed acres that backdrop many of Perry’s images are more fascinating – and perversely more glamorous – than most contemporary structures in the capital today. Collectively, these cries and warnings represent a precious archive, almost lost in plain sight, that should be seen as central rather than peripheral to the canon of literary London. |

Words Sukhdev Sandhu

The Writing On The Wall Image: Roger Perry |

|

|

||

|

|

||