|

|

||

|

A new exhibition at London’s Wellcome Collection explores the fascinating and ambiguous world of dirt and our ambivalent attitude towards it. “On the one hand, dirt is the stuff we spend a great deal of time and energy avoiding or trying to clean away,” says Kate Forde, the curator of the show. “On the other, dirt is the precious ground beneath our feet, it’s the earth that generates our food, the stuff that sustains and supports us. The planet’s ingenious methods of recycling waste (the aprocesses of decomposition and photosynthesis) are the very reasons for our survival.” The subject of dirt, whether that means dust, refuse, excrement, bacteria or soil, is vast. The exhibition’s organisers have placed dirt, and our quasi-religious zeal at getting rid of it, in six different contexts (home, street, hospital, museum, community and land) and in seven different cities. Our 21st-century preoccupation with germs and cleanliness is clearly not a new one. Dutch painter Pieter de Hooch depicted 17th-century maids and servants sweeping, mopping and washing pots in austere surroundings where domestic hygiene seems to be synonymous with morality; Joseph Lister introduced antiseptic surgery to Glasgow’s Royal Infirmary in the 1860s and so dramatically reduced post-operative mortality rates. The artist Bruce Nauman’s obsessive and mundane video footage of two pairs of hands endlessly washing seems more apt than ever in this context. There is hardly a dull moment in this exploration of filth but the quirky pieces are the most memorable. These include the haunting portrait of an Italian woman before and after contracting cholera (five hours after contracting the disease she was dead), and Paromita Vohra’s film on the state of public toilets (and who gets to use them) in India’s big cities; or the wall devoted to the photos, memoirs and letters detailing the bizarre 40-year relationship, and eventual marriage, between barrister Arthur Munby and scullery maid Hannah Cullwick in Victorian London. The former had a thing for working-class women whose jobs involved hard, physical labour and there are photographs of Cullwick dressed as a chimney sweep or posing covered in soot and dirt. Filth as fetish is certainly not a Victorian invention, and the exhibition highlights our simultaneous attraction and repulsion to the stuff. The fashion for slum tourism, which was prevalent in Victorian times and is also covered here, combined voyeurism and philanthropy and is not so different from modern-day reportage of starving African children with bloated bellies. Another section of the exhibition explores the practice of manual scavenging (cleaning latrines and sewers by hand), still widespread in many parts of India. One of the highlights of the show is an installation by controversial Spanish artist Santiago Sierra which consists of five large grey slabs made out of human faeces collected and dried by manual scavengers in New Delhi and Jaipur. Presented on the wooden crates they travelled in, the blocks are glossy and smooth and no longer smell since human excrement becomes inert after three years. They aren’t particularly interesting to look at, though I suspect the visual impact is greater when all the 21 slabs that make up the piece are laid out, but the contrast between their machine-made finish and Senthil Kumaran’s photos of the scavengers (some of them teenagers) at work, wearing scant clothing and, if they’re lucky, a plastic bag on their heads, makes for very uneasy viewing. The last room in the exhibition underlines our need to rid ourselves of dirt in every way we can, and unwittingly charts the extent of our dirt cover-up. Fresh Kills on Staten Island was at one time a lush and pristine marshland. In the second half of the 20th century it became the world’s largest municipal landfill, measuring almost three times the size of Central Park and reportedly visible from space. Photos and footage show the site before its closure in 2001 and the ongoing masterplan to turn it into a vast recreational park, replete with nature trails and restored tidal marshes, by 2030. “Today it’s pretty green and tranquil although there are goose-necked pipes emitting methane gas from the landfill dotted about and occasionally, on hot days, a pungent whiff in the air …” says Forde. The millions of tonnes of rubbish may have been covered with an artificial landscape, but they are still there. We may have got better at hiding our waste, but we still don’t really know how to deal with it. Dirt. Wellcome Collection, London. Until 31 August |

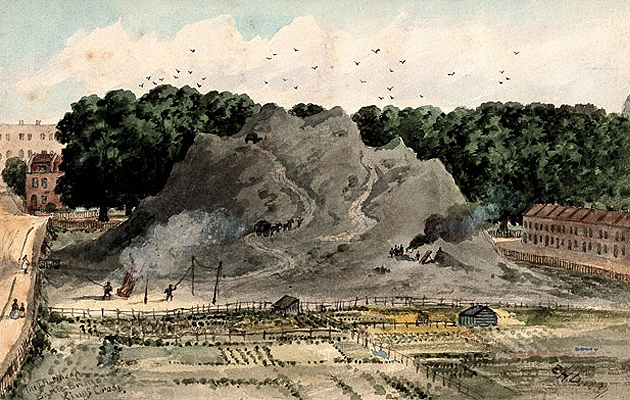

Image Wellcome Library, London

Words Giovanna Dunmall |

|

|

||