|

Something unbelievable has happened: farming has become fashionable. But only if you’re doing it in the middle of a city. In Britain, trend researcher Future Laboratory reports that some 15.5 million people now grow their own produce. In the USA, the rise in “urban homesteading” has been given presidential approval with the inauguration of a five-acre White House kitchen garden in April. Public attitudes towards food were already changing thanks to healthy eating campaigns and environmental concerns, and now the recession is focusing attention on self-reliance. Nearly everyone is thinking about food differently. “It’s insane to regard it as automatic that we get butter and vegetables and meat and so on in the supermarket just by turning up without thinking about where it comes from,” says John Thackara, director of design and sustainability network Doors of Perception. “There’s only three day’s supply of food in the average supermarket and, no, we don’t have food security in this country.” This worries governments too: in April, a G8 policy document warned that global food production must double by 2050 to ward off international chaos. In this moment of crisis, some architects believe they have found a near-universal solution. “Urban farming is really the holy grail of sustainable cities,” says Dan Wood, principal of New York-based architects Work AC. Wood’s firm is among a variety of practices pitching urban farming projects – an extraordinary diversity of proposals ranging from vertical agricultural megastructures in city centres and skyscraping pig farms through to visions of more traditional food cultivation woven into the city’s fabric, placed on rooftops, or even replacing whole neighbourhoods. Can urban farming really achieve all that is claimed of it? And what do the different models on offer mean for the city? At the most radical end of the urban farming spectrum is Dr Dickson Despommier. A microbiologist and ecologist at Columbia University in New York, he is a leading advocate of “vertical farming” – building towers and filling them with intensively reared crops in hydroponic systems. The aim is techno-environmentalism: almost completely lifting the burden of agriculture from the planet’s surface, and returning what is now countryside to its natural state, which in most cases is forest. The alternative is famine. “We farm an area essentially the size of South America,” says Despommier. “That feeds seven billion people. If you include the three billion who’ll be here in 40 years, there isn’t enough land given the current way of farming to feed those people.” Vertical farming, Despommier claims, is the only way to feed these new billions and undo the environmental destruction caused by our present agricultural model. The proposal amounts to stacking high-intensity, hydroponic greenhouses on top of each other in city centres. Some of the more ambitious, science-fiction renderings on Despommier’s website depict farming skyscrapers, but the building could only be five storeys high, and not particularly deep, so that natural light can penetrate to the crops. The best solution could be long and narrow, or small units above buildings such as schools and hotels. The bases of the farms would be giant greengrocers selling fresh food. This, Despommier says, would change the way we think about the city. “When we do this, it now becomes possible for a city to behave like an ecosystem, because ecosystems produce their own food, driven by sunlight,” he says. “Probably not all of [its food] – I concede that four-legged animals will probably not fit in this mould – but you could certainly do poultry, fish, molluscs and crustaceans without any trouble.” Vertical farming has received some serious architectural attention, and with four-legged animals involved. In 2001, Dutch firm MVRDV infamously designed “Pig City” for the Netherlands’ ministry of agriculture, a series of 40 multi-storey habitats for porkers. And Despommier says he has had interest from the United States Agency for International Development, which is examining the potential for vertical farms in less developed countries without large areas of agricultural land – Jordan is mentioned as a possible pilot. But Wood and Thackara are politely sceptical. “Industrial farming is not a sustainable model for the future, and for us vertical farms are more industrial farming – just another mechanised way to produce food,” says Wood. “Have you ever tasted a hydroponic tomato? The ones that taste like nothing are often grown hydroponically.” “It’s a fun subject, but in terms of feeding cities, vertical farms are not going to be the answer,” Thackara says, citing the cost, complexity and high maintenance requirements of a vertical farm. “The answer is going to be disused and unused space, large numbers of relatively small plots, bits of land that can’t be used for anything else, combined with new forms of social organisation for people to look after all these things in an effective way.”

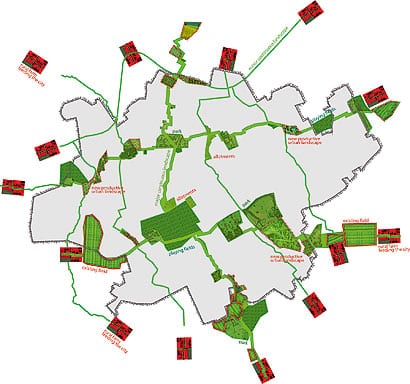

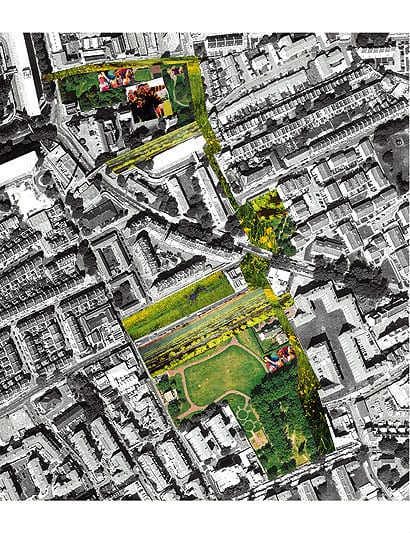

Front Studio’s Farmadelphia project proposed refitting residential buildings for agricultural purposes Wood’s solution is to put farms on rooftops. Work AC’s Public Farm 1 pavilion last year demonstrated how to elevate productive space, creating a usable social area underneath it. Public Farm 1 also trialled a high-tech soil made out of compost and recycled Styrofoam that is only one-quarter the weight of normal dirt, which circumvents the usual structural problem with rooftop farming. And there are already rooftop farming systems on the market. Keith Agoada, an entrepreneur based in Berkeley, California, runs a company called Sky Vegetables, which aims to put high-yield farms on the flat roofs of big-box supermarkets – a vast area of unused space directly above food distribution points. For Agoada, this addresses the most wasteful aspect of the way we presently grow food: distribution. “Last year the United States spent $550 billion [£380 billion] through the food distribution industry – that’s mostly just moving food around,” he says. Thackara, for his part, has been working with Bohn & Viljoen Architects, a London-based practice with a longstanding interest in urban agriculture, to develop his ideas. Bohn & Viljoen’s concept is the “continuous productive urban landscape” (CPUL) – a way of connecting parcels of disused land into green fingers running through cities, and dedicating these spaces to growing food. “We tried to create a design vision that would combine a landscape proposal for a contemporary city with a use proposal,” says partner Katrin Bohn, presenting the CPUL as parkland with “a user concept that goes beyond benches and tennis courts”. Turned earth and cabbage patches might not seem like a very attractive vision for parks, but Thackara thinks that attitudes will change as perceptions about the environment change: “In another year or so people will look at a large green lawn as the SUV of gardens, while something with food growing on it and people pottering about will look more animated and pleasant.” The CPUL has been tried in practice, in Middlesbrough, Yorkshire. As part of the Designs of the Time festival in 2007 – directed by Thackara – a portion of one of the city’s parks was partly turned over to agriculture, and more than 1,000 people began growing food in containers. The project has recently been awarded another £4m in funding by the council to extend its work. A similar project, on a much vaster scale, has been outlined by Jean Nouvel as part of the Grand Paris ideas competition, in which architects were invited to imagine bold futures for the French capital. Nouvel proposed ringing the city with a 620 mile-long belt green belt. This would be given over to suburbanites to cultivate, giving a sense of shared identity and purpose to the depressed and restless banlieues. However, there are more radical proposals for ruralising the city. In Monsanto New Garden Suburb, London’s AOC Architecture imagined the controversial agribusiness giant salvaging its tarnished UK reputation by wreaking an agricultural revolution in Hackney. The proposal – which GM food producer Monsanto did not endorse – imagined the borough turned over to organic strip farming and becoming a “living advertisement” for the corporation. The city’s hard infrastructure would become obsolete, with streets replaced by grass, and buildings removed from the grid. “[Structures] collect their own rainwater, they generate their own electricity, which means they get away from the traditional hard city of pipes in the road and move toward a soft city in which each building is autonomous,” says AOC principal Geoff Shearcroft. A similar conceptual scheme is “Farmadelphia”, by New York architectural practice Front Studio, which would regenerate and reinvent the identity of the troubled city of Philadelphia. Farmadelphia proposed converting whole blocks of the city to commercial agriculture, clearing ruined houses and converting the surviving buildings in houses, barns and farm offices. Once a site had been cleared, it would be planted with sunflowers to naturally clean the soil – a slow but symbolically important process. “It was a way for us to mark our territory, so that the city knew that if you came across a sunflower field it was part of Farmadelphia,” says Michi Yanagishita, one of Front Studio’s two principals. “It could become an icon.”

Pyramid Farm by Eric Ellingsen and Dickson Despommier However, there’s something troubling behind the chirpy utopianism of urban farming. At times, it feels like planning for a future that is almost post-apocalyptic. The most commonly cited case studies for successful urban farming are the American city of Detroit and the Cuban capital Havana – both venues of economic disaster, where the cultivation of urban land has been a necessity, not a choice. Isn’t there something gloomy about this kind of proposal? “It is slightly pessimistic,” says Shearcroft. “But I think once it becomes more of a reality, people start to enjoy it more. It will pass a tipping point where it’s less about necessity and it’s about delight.” Nevertheless, turning city blocks back into farmland feels like surrendering the modern ideal of the city, a form of planned ruin. But in Work AC’s vision, that’s really a matter of where you’re standing. Wood suggests a regional approach – farmland will go organic, the city will sprout rooftop farms, inner suburbs will become more dense and urban, and sprawling car-dependent exurbs will return to agriculture. “So for us it’s more of a forward-looking visionary approach to the city than some romantic idea of the city of nature. Our term for it is ‘rurbalisation’.” This regional vision points to the most realistic way of thinking about urban farming. Even with the best rates of productivity achieved, these low-tech, organic approaches such as Bohn & Viljoen’s CPUL will never completely feed the city from its spare land. “We did a calculation that you could produce maybe 30 percent of [London’s needed] food, growing fruit and veg,” says Katrin Bohn. “And 30 percent is massive, it’s really a lot, but also it’s only 30 percent.” (Work AC’s rooftop model, Wood claims, could generate far higher yields.) But the really valuable thing about the CPUL concept is not necessarily the way that it brings food-growing into the city centre, but the way it forms visible links between the city and the pre-existing farms that surround it. The city and its agricultural neighbourhood are stitched together into – as suggested by the CPUL name – a continuous landscape. It’s this shift in perception that could be the most important result of all these strands of urban farming research. The modern notion of city and countryside as separate things is challenged and instead the city and its hinterland is viewed as a single construct, a continuum. This is where the sci-fi visions of Despommier and his supporters overlap with the less high-tech model of vacant lots and multiplying vegetable patches. Both positions present a vision of the city as a self-feeding ecosystem as opposed to a brick-and-steel machine that is permanently consuming fuel and producing waste. For Despommier, that system could be a self-contained island in the midst of parks and wilderness. For Thackara and Wood, it’s a patchwork of neighbouring bioregions, each consisting of a city and the cultivable land that surrounds it. In either case, the new thinking on urban farming boils down to an abandonment of the modern conceit that we can ignore the origins of our food.

Image from Farmadelphia

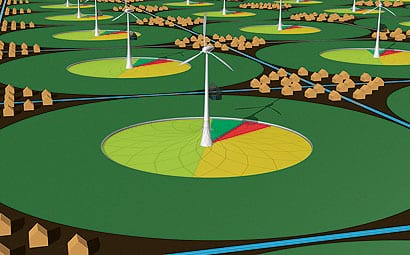

Oogst 1 and Oogst 2, two conceptual projects by Frank Tjepkema

Oogst 1 and Oogst 2, two conceptual projects by Frank Tjepkema

Oogst 1 and Oogst 2, two conceptual projects by Frank Tjepkema

Bohn & Viljoen’s CPUL concept, productive corridors linking local farms to city centres

Bohn & Viljoen’s CPUL concept, productive corridors linking local farms to city centres |

Image Monica Nouwens

Words William Wiles |

|

|

||

|

An image from Front Studio’s Farmadelphia |

||