|

The museum and the lower auditorium are linked by partially buried walkway |

||

|

Hamarøy is like a Knut Hamsun theme park. In this district, 500km above the Arctic Circle, Hamsun’s name means business. You can pick up a “Realm of Hamsun” map and follow in the footsteps of Norway’s most famous novelist: his childhood home, the farm he bought in 1911 and the former general store where he worked for a year. Now, in the tiny village of Presteid, Steven Holl is putting the finishing touches to a museum in his honour – a project complicated by the darker aspects of the author’s life. The Hamsun centre doesn’t open to the public until June next year, yet there is a constant stream of camper vans stopping in the desolate car park, bringing nature enthusiasts dressed in waterproofs to its entrance. Noses pressed against the glass, hands trying to force the locked door, it is obvious that the Hamsun centre is already the tourist attraction the municipality of Hamarøy hoped for. “I’m amazed that so many people want to come and see it even now,” says Bodil Börset, research fellow in comparative literature and director of the Hamsun centre. She is tired, still recovering from the celebrations the week before marking the 150th anniversary of Hamsun’s birth. For a few days the unfinished museum opened to the public and 6,000 people turned up. It’s impressive traffic for a tiny village of a few hundred inhabitants largely made up of a fishing and camping site of little red cabins with grass roofs along the Glimma, a roaring tidal stream. Holl’s building has been a long time coming. Back in the early 1990s, when he was working on the Kiasma museum in Helsinki, Holl was invited to present ideas for the centre by local politician Auslag Vaa, who controversially decided to forego the conventional invited competition. Holl presented the first sketches to the local community in 1994. “I have been told that his presentation was met with complete silence,” says Børset. “Then the debate started; people were very shocked by his proposal, some loved it, others thought it was crazy.” However, the building has emerged almost exactly as it was sketched out all those years ago. “What’s a thrill to me is that it’s now 15 years old but I wouldn’t change a thing about it,” says Holl. “It’s unique to this site.” In this setting of never-ending mountains and surreal grandeur most buildings have admitted defeat by crawling along the ground. There’s a modernist church in white concrete by Nils Toft from 1974 but nothing has challenged the scenery quite like Steven Holl’s tilted five-storey museum clad in tarred timber. The centre comprises a museum tower and a low-lying auditorium. The tower shoots up between the trees, sprouting hair and oddly shaped appendages that appear to beckon nature according to some ancient ritual. It takes on almost human qualities: the front facade resembles an oversized mask from some animist religion. In the gloomy weather, it looks troubled and deep in thought. As the rain starts falling it becomes one with nature, a monument rather than architecture, a troll in a fairy-tale landscape. Hunger, Hamsun’s 1890 debut which tells the semi-autobiographical story of a starving vagrant, is viewed as the literary start of the 20th century – and Hamsun considered the first modern writer. His first-person narratives have influenced everyone from Franz Kafka to Paul Auster. He became a national treasure, but a darker side to his story took shape. As an older man he became involved with Norway’s nationalist party, Nasjonal Samling, and during the Second World War was pro-German as well as a supporter of the occupying Nazi government. After the war he was tried, but never prosecuted, for treason. After psychiatric tests he was, at the age of 82, deemed mentally incapacitated.

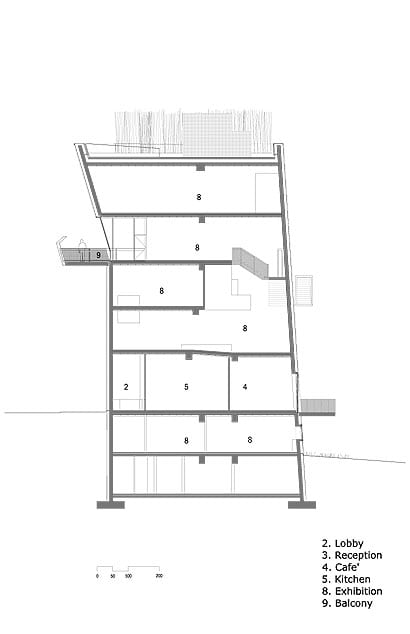

Presteid, 500km north of the Arctic Circle Norway dealt with the Hamsun problem by writing off the aged politician in order to continue celebrating the young writer. But the soft opening of the Hamsunsenteret revived the debate in Norwegian and Scandinavian newspapers and Börset found herself in the midst of a political storm. How does Holl’s building reflect the author – and handle his troubled legacy? “The idea is to make a building based on a novel,” says Holl. The first thing he did was re-read Hunger and acquaint himself with other early novels such as Mysteries and Pan. It was the troubled characters and surreal situations of these psychological novels that influenced Holl. It is a bewildering experience to make your way through the building, as it seems to have limitless angles and vistas. No room is entirely square, instead the walls have unexpected creases where it follows the fold of the top left hand corner of the exterior wall. Holl describes it as “building as a body with invisible forces that fight each other.” In sunny weather this experience intensifies as beams of sunlight create rooms within rooms from otherwise invisible grids. The museum’s core is a spine of perforated sheets of brass that conceal the lift shaft. When the lift has been installed, Holl intends the visit to start by taking the lift to the top floor, then you’ll wind your way down through the building by foot, in a vertical rather than horizontal promenade. When the exhibition architects and builders have finished their bit next year you will be taken through Hamsun’s life and work, primarily through digital projections, but today the rooms are empty. The walls are shuttered concrete stained white and the floor is black concrete with gravel mixed in, alluding to the texture of the mountains outside. Holl has enjoyed playing games with the architecture and the surroundings of the Hamsun centre. Sometimes he makes the most of the building’s position in the landscape, on the top floor for example, he has positioned a window resembling an open book in one corner, giving you full access to the nature outside. At other points he puts windows at either extremely high or low heights, making you feel like you are in a room that is slowly falling, and darkening the mood by making interaction with the surroundings impossible. At one point the top of a staircase is designed to feel like a dead end. The roof is the most dramatic spot of the building, as it gives you a 360 degree view of the mountains, but also the weakest. The cramped space is edged by tall bamboo rods anchored in concrete. This is a reference to Norwegian vernacular architecture, but the finished result is a poor copy of the floppy grass that grows on so many traditional Norwegian log houses. “We were struggling with the hair,” says Holl. “We couldn’t find any grasses that would stand in winter so I said let’s do bamboo.” From afar the effect is successful, the spiky mane of a giant, but up close it feels like a foreign material in what is otherwise such a well-considered building.

The building is clad in tarred timber The Hamsun centre is full of literary references, and sometimes they feel rather laboured. For example, the yellow glass balcony in the building’s northern corner refers to a maid polishing yellow window panes in Hunger. The southern facing balcony in Cedar wood is a reference to an empty violin case in Mysteries. Instead of adding poetic touches, these heighten the sensation of being in a Hamsun theme park, where you can buy your Hamsun mug and T-shirt at the exit. It is the subtler details and the mood that the building creates that are its real strength – it’s like an existential mind game. The Hamsun centre’s deliberate contradictions can also be seen as a comment on Hamsun himself. When he designed the building Holl was unaware of the full extent of Hamsun’s political leanings (he gave his Nobel prize medal to Goebbels in 1943), and so hasn’t made any explicit references to those episodes. However, it is now easy to read that backstory in the building’s gloomy recesses. It is also fitting that the Hamsun centre is positioned in this remote spot in northern Norway: not only because Hamsun himself spent his childhood here and throughout his life preferred nature to the negative effects of modern urban life, but because it perfectly communicates Norway’s ambivalence to its most famous author and the country’s own collaborationism. Of course Hamsun should have a museum, but it’s no coincidence that it’s not in Oslo but tucked away here in Presteid, 500km north of the Arctic circle.

A cedar balcony inspired by the empty violin case in Mysteries

Light cuts the stairwell around the brass lift shaft

The promenade leads to a balcony

The book-style window on the top floor

|

Image Marcus Ross & Iwan Baan

Words Johanna Agerman |

|

|

||

|

The tower’s bamboo “hair” echoes local buildings

The first-floor gallery with its sloping floor and inaccessible window |

||