|

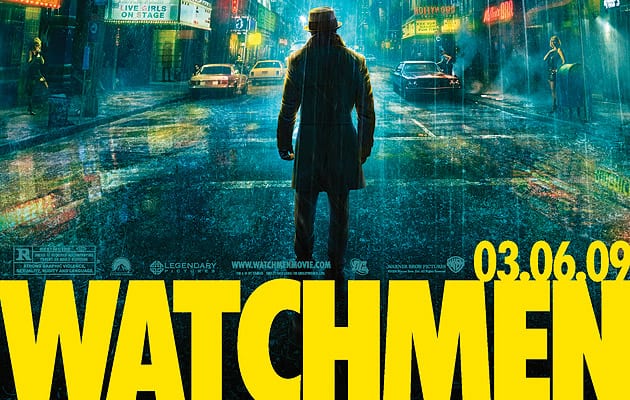

image: Paramount Pictures |

||

|

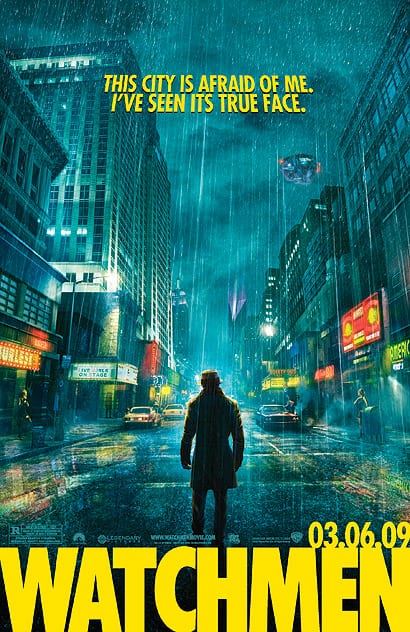

Masked vigilantes put the psycho into psychogeography in Zack Snyder’s ultraviolent film, a tirade against the evils of the city. William Wiles watched. If it wasn’t for his mask, Rorschach would just be a psychopathic tramp. With the mask – a white hood with an endlessly shifting inkblot design – he’s a superhero, one of the eponymous Watchmen in Zack Snyder’s adaptation of the seminal Alan Moore graphic novel. Rorschach is also an urbanist of sorts, filling a diary (the device that narrates the film) with obsessive musings on the city: it “screams like an abattoir full of retarded children … this city is afraid of me … I’ve seen its true face.” Needless to say, he doesn’t much like what he sees. The city in Watchmen is an alternative New York, but it could be anywhere, provided that anywhere was dragged from the worst imaginings of an exurban Reaganite. It is a rat’s maze of endemic violence, crime, chaos and sleaze. The constant rain never seems to make it any cleaner. It’s not a place with problems, it is the problem. The Watchmen are a response to all this chaos. They are a disparate group of costumed vigilantes, one of whom has genuine superpowers: Doctor Manhattan, the blue-skinned triumph of the arms race. The others are simply bright, well-equipped and good with their fists. Their efforts, however, do not do any good: the city declines, president Nixon is in his fifth term and the world is on the brink of nuclear oblivion. Doc Manhattan and billionaire industrialist Adrian Veidt, “Ozymandias”, are trying to defuse apocalypse, Rorschach is breaking heads on the street, and the other Watchmen are in retirement. To bring Moore’s multilayered, intricate story to the screen, Snyder has had to compress it. A reflective and meandering tale has become a high-intensity 162-minute blizzard of violence. Moore’s Watchmen is about the limitations of power. Snyder turns this sense of limitation into a vaguely fascist frustration with tangled modernity, a craving for simplicity, with the city playing the role of the complicated, corrupt villain. In the book, there are interludes involving a news vendor and the boy who sits by his booth reading comic books. These scenes, embedded in artist Dave Gibbons’ richly detailed and witty streetscape, humanise the city. In the film, the urban vision is unremittingly bleak. This city’s face, like Rorschach’s, is blotted out: the street level is a stew of neon, graffiti, darkness and rain. The architecture of the film is all at a safe distance from this nightmare: Doc Manhattan’s glass temple on unspoiled Mars, and Veidt’s Antarctic hideaway and corporate suites, where he has developed a plan to save the world from atomic destruction. In the book, to save the city it becomes necessary to visit unimaginable horror upon it. The film goes even further, and the solution to the world’s problems is now comprehensive urban redevelopment. But Rorschach’s diary, detailing his exploration of the city, is the wild card, and an act of corporate sterilisation could yet be undone by psychogeography – surely the supreme fantasy of the Iain Sinclair tendency. image: Paramount Pictures Watchmen is on general release |

Words William Wiles |

|

|

||