|

|

||

|

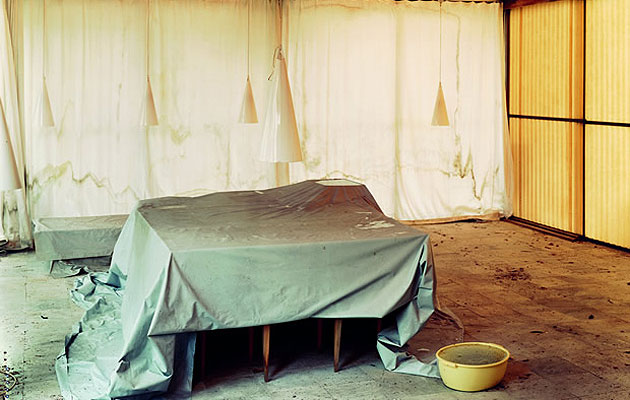

There is a certain kind of architectural experience, one of frustrated tourism. You make an awkward journey to an out-of-the-way building and then find yourself peering over a wall, furtively opening a rusty gate or waiting for someone to come in so you can tailgate them into a hall. It is the exact opposite of the architectural monograph experience in which every image is composed and perfected – the result of prolonged exposure and full access. This monograph by the photographer Mikael Olsson is extraordinary, because it inhabits the former experience. The paradox makes for a curious and arresting book. Swedish furniture designer Bruno Mathsson (1907-1988) built himself two houses in the early sixties: Södrakull, a Miesian, California-inflected glass and timber box, built in 1964-65; and Frösakull, a sparse summer house built in 1960. Like a proto-Gehry, Mathsson built Frösakull using materials that were available: corrugated metal, plastic sheets, plywood, spindly timbers and old curtains. The designer grew old and died, the house deteriorated, and when his widow died in 1999 it was left empty. A year later architect Thomas Sandell (of Sandell Sandberg) bought the house as a retreat for his staff. None of them, according to Helena Mathsson’s essay in the book, “showed any particular interest”. It was sold again, this time after Sandell had initiated a move to have it listed. It went at auction in 2006, sold not as a building but as part of a furniture sale.

The photos here are not so much a documentation – though they are that as well – but more an exploration of decay and the awkward relationship of modernism with imperfection. Mathsson had been hugely influenced by Philip Johnson and the Case Study Houses and he brought that version of American modernism, – itself so heavily influenced by northern and central Europe via Mies van der Rohe, Neutra and Schindler – back to Sweden, where he designed glass houses and this extraordinarily modest little structure for himself. The first photos of the more solid, if still ethereal, Södrakull main residence offer mere glimpses of the structure, snatched, voyeuristic snippets of building between trees, ajar doors and partially-drawn hangings. Like Thomas Ruff’s photos of Mies van der Rohe’s buildings, they distort and question perfection though movement and blur. It is an odd kind of voyeurism that targets the structure rather than its occupants. Who spies on a building? Well, we do, of course. The other photos, of the Frösakull summer house, are more invasive, interfering with the remains – there is something slightly creepy about the documentation of the decaying house of a dead man. There are moments when, in Olsson’s increasingly mesmeric photos, you see glimpses of a Miesian perfection. But mostly the images convey neglect; the forest spreading into the interior as the dim northern light just about manages to penetrate the algae-encrusted plastic sheeting. Thomas Demand has made us look carefully at the perfection of the photographed architectural interior: it is the smoothness of the surfaces and the dryness of the cardboard that lets you into the secret. In Olsson’s photos it is quite the opposite – the structural simplicity is made complex by the oddly beautiful staining, the artful distribution of leaves on the ground and the glimpses of a grey sky that give the lie to the architecture’s sunny modernist sensibility. This book tells you more about the qualities of a building, about space, time, texture, modernity and mortality than a million words or a dozen meticulously made monographs. Södrakull Frösakull, Mikael Olsson, texts by Beatriz Colomina, Hans Irrek and Helena Mathsson, Steidl, £48 |

Image Mikael Olsson

Words Edwin Heathcote |

|

|

||

|

|

||