|

|

||

|

A show in Copenhagen examines why Danish architects and designers have drawn so much inspiration from a country on the other side of the globe, says Mille Collin Flaherty It is striking how obvious reference is in a number of objects displayed in the east wing of Copenhagen’s Design Museum Denmark. The wooden salad bowl designed by Danish silversmith and designer Kay Bojesen in 1979, for example, is shown next to a similar bowl made by artisans in Japan. While Bojesen’s bowl is made from teak and feels heavy and robust when you pick it up, the Japanese model seems light and airy, almost gossamer, compared to its Danish equivalent. One could argue – as does the exhibition’s architect Elisabeth Topsøe, who is in the middle of setting up “Learning from Japan” when I stop by – that Bojesen aimed to create an exact replica. In so, he captured the idiom, but utterly failed to grasp the bowl’s elegance. Not that the exhibition is pointing fingers at the Danes: the Bojesen bowl and most of the Danish items on show are considered to be design classics, but it is astonishing to see how much the country’s designers, architects, silversmiths, textile designers and ceramists have learned from Japan – and, maybe more so, what the western world may never fully understand, yet alone imitate, about Japanese arts and crafts. But let’s stick to the issue at hand: Who knew, for example, that Danish national treasures such as Bing & Grøndahl’s Seagull dinnerware set and Bindesbøll’s ceramics were in part influenced by Japanese designs? That Poul Kjærholm’s Folding Stool is inspired by basic origami techniques and that his PK61 table is based on the principles of tatami ceremonial spaces? Or about the influence of Japanese architecture on Danish homes in the 1950s and 60s, as well as on Jørgen Bo and Wilhelm Wohlert’s Louisiana Museum of Modern Art?

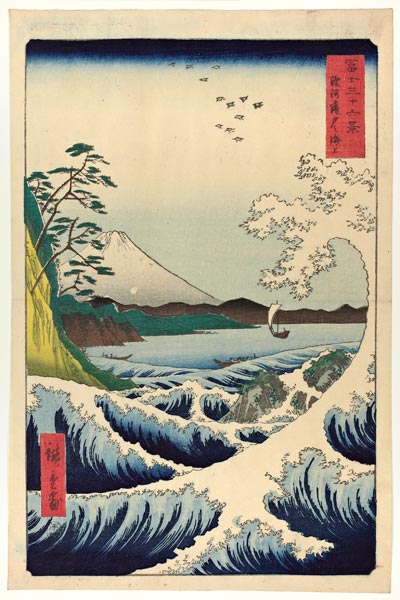

Lake Satta in Surega Province: 1858 ukiyo-e by Hiroshige Ando “Learning from Japan” is curated by Mirjam Gelfer-Jørgensen, author of the 2013 book “Influences from Japan in Danish Art & Design 1870-2010”. The exhibition is largely based on her research and is centred on the question: why is it that Danish architecture and applied art have drawn lessons and inspiration from a country on the other side of the globe, with a social context that is fundamentally different? The history of “Japonisme” in Denmark can be described as a curve, and the exhibition is informally divided into the two major peaks of influence of Japan on the West. The first wave was in the 1850s when the US opened up the gates to Japan after 250 years of isolation. Not only did this instigate a trade revolution, it also paved the way for the largest impact on art and design in Danish history. In fact, the impact of Japan was so extensive that it became an essential precondition for Danish modernism in the 20th century and for the country’s status in the design world today. Japan had maintained its cultural homogeneity for more than a thousand years until this period, when its culture was absorbed by a group of creatives in the West. Some even argue that the Japanese ukiyo-e woodcuts of the time should be credited for the fame of such artists as Manet, Monet, Gauguin, Toulouse-Lautrec and van Gogh. In Denmark the new currents were picked up by one person in particular: artist Pietro Krohn, who in 1893 became the first director for the museum today known as Design Museum Denmark. It is this connection that really makes the exhibition shine. All the exhibited items are from the private collection of the museum and, as a visitor, it is almost as if you see the beautifully ornamented ceramics, textiles, woodcuts, lacquered pieces and the extensive collection of sword-guards, the so-called tsubas – with waves, crane, flower and fish motifs –through the eyes of the great collector Krohn.

Effie Hegermann-Lindencrone: Sculpture and vase, Bing & Grøndahl’s Porcelain Factory (vase from 1913, the sculpture from before 1918)

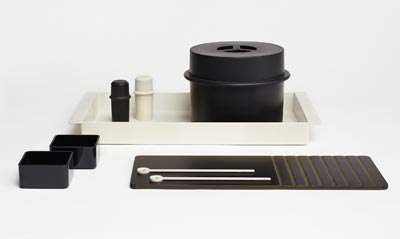

Knud Holscher’s Club Manhattan serving series, made by Stone Art, Belgium, 1985 The stunning pieces from Danish contemporary artists such as Thorvald Bindesbøll, Carl Petersen, Anton Michelsen and Pietro Krohn himself reveal the zeal with which they absorbed this new vocabulary and made it their own. Around 1950, there was another wave, and in the second half of the exhibition, familiar furniture and design pieces such as the folding lamps from Le Klint, enamel bowls by Herbert Krenchel, ceramic items from Ursula Munch-Petersen and Richard Manz and architecture by Halldor Gunnlögsson and Jørn Utzon are displayed next to traditional Japanese raku-burned stoneware, woodwork, kimonos, textiles, iron pots with pine lids, tatami straw mats, origami folded paper and the Butterfly stool made by Tendo in Japan in 1956. Gelfer-Jørgensen calls the connection between Danish and Japanese design vocabulary an “aesthetic kinship” rather than an inspirational one. “The process was not one of imitating Japanese art, but of transforming it into an independent language,” she writes in her book. At the exhibition, she tells the widely untold story of the connection between the two visual languages – and the strength of both. |

Words Mille Collin Flaherty

Above: Snorre Stephensen: Tray, teak and formica with pieces of porcelain dishes for serving a Japanese meal, 1984

Learning From Japan |

|

|

||

|

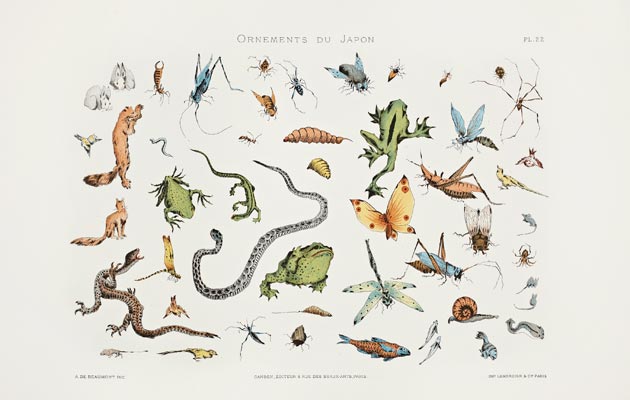

Page from E. Collinot and A. de Beaumont’s Ornements du Japon, recueil de dessins pour l’art et l’industrie, 1883 |

||