|

|

||

|

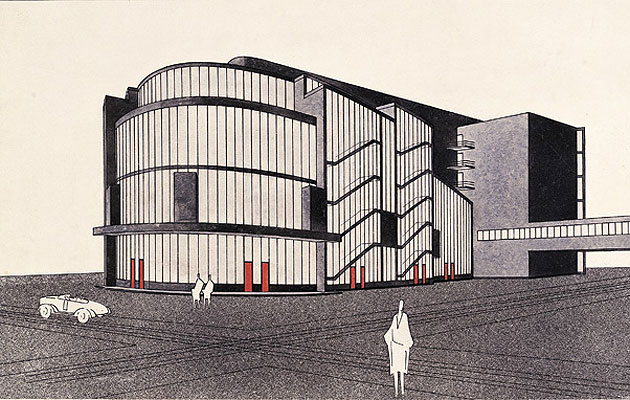

Stefan Sebök was an architectural Zelig. It would be difficult to conjure up a character who worked deeper in the heart of successive avant gardes yet one less known – or less lucky. Sebök was born in Hungary in 1901 and was part of an extraordinary Hungarian modernist diaspora that included László Moholy-Nagy, Marcel Breuer, Farkas Molnár (who designed the Red Cube House, the first modernist building design to come out of the Bauhaus), Ernö Goldfinger and dozens of others who fled either the anti-Jewish laws in their home country (which denied them the chance to study or teach at universities) or the lack of architectural opportunities. Sebök, like many Hungarians, landed in Germany. He worked at first for Walter Gropius and it is his name inscribed on the hugely influential drawings for the unbuilt “Total Theatre” designed for Erwin Piscator – a staple of illustrated modernist histories and more influential than any realised building could be. But Sebök was more than just a draughtsman – it appears his student work prefigured Gropius’s designs and his input in his office was indispensable.

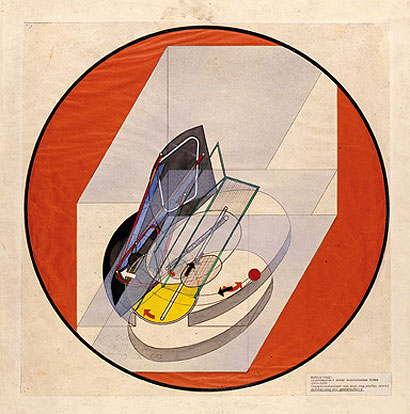

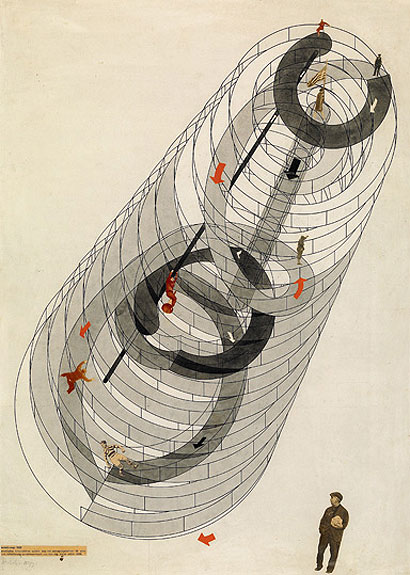

From there he went to work with fellow Hungarian Moholy-Nagy, and was instrumental in the design and execution of the wonderful Light-Space Modulator series of constructivist kinetic sculptures, which have themselves become permanent fixtures in modernist collections. From there, Sebök travelled to the Soviet Union, where he joined other idealistic leftists (including Hannes Meyer, the director of the Bauhaus who succeeded Gropius) in attempting to build a new, socialist world. There he went to work for the Vesnin brothers, Victor and Leonid, among the most influential figures in constructivism and designers of the Pravda building and the unbuilt Moscow Palace of Labour. As Stalinist bombastic classicism took root, the Vesnin brothers were among the last architects to hold on to a modernist vision, as their steel and glass 1934 design for the Palace of the Soviets shows. Eventually even the Vesnins caved in to the classical, though their designs for the Moscow metro stations do represent a high point of socialist architecture, arguably coming closer to the idea of “palaces for the people” than anything before or since. Sebök’s meticulous perspective renderings for these are a delight, with real parallels to Frank Pick’s London Underground designs. Sebök also crammed in spells in the offices of Moisei Ginzburg and El Lissitzky, the most inventive of all the constructivists. But, like so many dedicated socialists, he ultimately fell victim to Stalin’s purges and disappeared into the gulags. He may have been at the centre of European modernism, but he ended his life a marginal figure, forgotten in the camps many miles from home and forgotten in the annals of architecture.

This book, by Lilly Dubowitz, a London-based retired doctor and Sebök’s niece, is a slightly unconventional monograph. It tells the story of Dubowitz’s research into her uncle’s complex past and is supplemented by two contextual essays: one on the Bauhaus’s Hungarian emigrés by Eva Forgacs and another on the international nature of Soviet architecture between the wars by Richard Anderson. The general nature of those two essays reveals the fundamental hole at the centre of the story – Sebök himself. Despite Dubowitz’s extensive research and a surprising number of photos, the architect is barely present. However in the drawings he appears like a wonderful ghost. They begin with townscapes and rich, vigorously expressionist self-portraits. The architectural drawings and documents, copied here in all their crumpled, dog-eared detail, are wonderful and refreshingly unfamiliar. They are a window into two decades, in which architects moved from radical, experimental constructivism, through international modernism, to classically inflected socialist realism. Sebök may have been a minor modernist figure, but his short life embraced the most radical upheavals in architectural and socio-political history. With its achingly poignant mug-shot cover, mistitled in handwritten Cyrillic characters, a careless moment of bungled Soviet bureaucracy, this is a real find. Finally, designer Zak Kyes deserves a credit here for an inventive job: a striking cover and a book design that feels sympathetic to its subject and is a fine tribute to crisp, modernist clarity. In Search of a Forgotten Architect: Stefan Sebök 1901-41 by Lilly Dubowitz, Architectural Association, £30. |

Image Busch-Reisinger Museum, Cambridge, MA; Theatre Museum, Cologne

Words Edwin Heathcote |

|

|

||