|

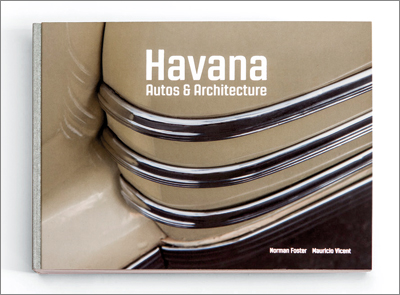

The Cuban capital, as captured by photographer Nigel Young, is a curious slice of classic America spared capitalism’s built-in obsolescence, writes Owen Hatherley As architects’ vanity projects go, Havana: Autos and Architecture is one of the more interesting. Credited to an unequal partnership of Norman Foster (writing one essay), El Pais’s Cuba correspondent Mauricio Vicent (writing 80 per cent of the text) and Foster & Partners’ photographer Nigel Young (whose images take up almost every page), and published by Foster’s wife Elena Ochoa, it is a strange combination of coffee-table tourism and classic-car fetishism. Most of the book comprises photographs of cars that have survived in use across the Cuban capital since the revolution of 1959, in front of various notable examples of the city’s architecture. These are then combined with some profiles of classic-car owners and a few lightly sketched urban and historical portraits. It sounds terrible, but it’s actually rather intriguing. Just recently, Barack Obama took the de facto decision to lift the US’s half-century blockade of Cuba. Its effects had been exacerbated greatly in the 1990s, when the island’s “fraternal countries” in Eastern Europe abruptly stopped subsidies. Non-aesthetic changes since 1959 are many – Cuba has the highest life expectancy in the region, the lowest unemployment and lower infant mortality than the US – but to the eye trained to expect a revolution to have tangible effects on the built environment, Havana presents, to quote the Baron of Thames Bank, “a time warp of suspended decay”. The most obvious aspects of this, bar the lack of new buildings in the centre, are the 70,000 pre-revolutionary cars still in use. So you’ll find the 1929 Capitol, a great Washingtonian dome, alongside a surviving 1929 Ford A, which “runs on kerosene and cooking fuel”, or a 1949 Bauhaus villa that looks more modern than the 1959 Austin parked outside.

A 1958 Rambler with outside the 1913 Ursulinas Palace, a building that reveals the Arabic influences on some Cuban architecture in the early twentieth century Young’s photographs show streets that are often dilapidated, but Havana looks in far better shape than Detroit, where most of these cars were built. Even so, it often seems that the authors would rather tell an American than a Cuban history, with boring anecdotes about Hemingway or Lucky Luciano. The photographs tell a less cliched tale. The only post-revolutionary buildings included here are the now famous series of National Art Schools built in the 1960s on top of the golf courses once used by the city’s (segregated, mafia-dominated) elite – the wild colours and swooping, winged forms of the Chevys and Pontiacs look more out of place against these ground-hugging, organic domes in brick and concrete than they do against the deco and baroque that dominates the city centre. There is, as you’d expect, little thought about just how strange it is that a country that has – amazingly successfully – resisted the US for decades preserves in its streets an image of “classic” America, the sunny, ultramodern country of mid-century dreams. We’re told that Cuba does have truly “Soviet” things such as prefab mass housing and badly designed cars but, bar a single Lada and the (fittingly flamboyant) Soviet embassy, we are not shown them.

The close-ups of the cars’ details go right into boys’ toys territory, but there’s something appropriate about how these American aesthetic objects have been fitted with Soviet engines to make them run. In fact, according to Havana historian Eusebio Leal Spengler (who writes the introduction), “the classic cars are reminders of a time when industrial products were not designed to cease functioning after a certain time”. This is a world without in-built obsolescence. It looks great, but only because it has accidentally pickled an era when cars were designed as objects of psychosexual obsession rather than functional, useful goods; for the Baron, they’re true survivals of capitalism, preserving a “pride in possession and the innate desire for the individual to stand out from the crowd” in the “levelling greyness” of socialism. At the end, though, Foster worries that, as Cubans are now allowed to own property, Havana may soon be as drab as any other capital. Boring enough, maybe, to commission some Foster-designed buildings. |

Words Owen Hatherley

Havana: Autos and Architecture

Images: Nigel Young, courtesy of ivorypress |

|

|

An art nouveau house in Calle Cárdenas, Havana, by the Catalonian architect Mario Rotllant, 1910