|

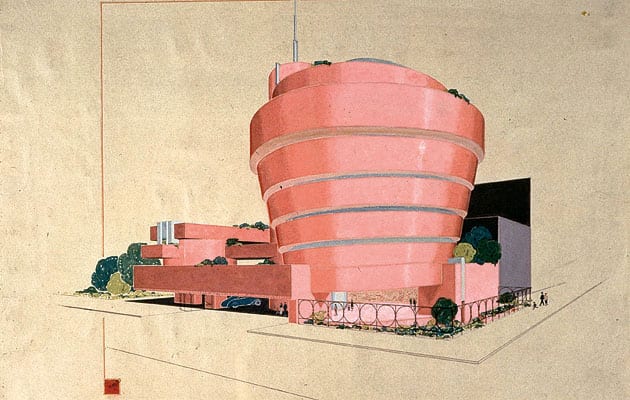

Drawing of Guggenheim Museum, New York, 1943-59 (image: © 2009 The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation) |

||

|

The life’s work of Frank Lloyd Wright gets somewhat lost in the monumental ramped space of his masterpiece – but his relevance is still clear, says Alex Pasternack. Could a retrospective of Frank Lloyd Wright have been held anywhere else but at New York’s Guggenheim Museum? Wright’s iconic rotunda is a fantastic setting in which to look back (and up, and down and sideways) upon the unprecedented assemblage of drawings, models and animations that fill this 50-year anniversary show. And that’s how Wright would have wanted it. It isn’t often that an architect’s retrospective ends up inside his own masterpiece. Still, this may also be the wrong place for a Wright exhibition. The museum is a monument to Wright’s stubborn genius, but put it on display inside the monument, and that genius gets upstaged. The vitrines and wall texts are scattered in vaguely historical procession upwards along the ramp, beneath a skylight dimmed in deference to some of the delicate drawings – creating an unreal vibe. The building and its shows tend to illuminate each other best when large sculptures or site-specific installations take over the hypnotic space. Wright’s work, all of it professing a love for the wide-open spaces of the American frontier, almost cowers before the wide open space of the museum. But the real void at the centre of the show is Wright himself. The show offers a taste of the democratic instinct of his churches and corporate headquarters, but the missionary zeal that drove his attempt to remodel American society barely registers. And while the show offers a hearty glimpse of the domestic utopian vision Wright elaborated in his houses, it glosses over the details of his own complex home life. These details, to say nothing of Wright’s roots or his notorious vanity and imperiousness, may not be essential to appreciating the work. But their absence and the show’s dreariness keeps Wright encased in glass and at arm’s length. That Wright may be more relevant than ever is only implied. Touring seven decades of Wright’s greatest hits might lead us to speculate about what he might have achieved with acrobatic engineering, parametric design and green technologies. The gorgeous drawings and watercolours bring us back to Wright’s earth, however. And new animations and models breathe some life into projects unbuilt or destroyed, such as the Larkin Company Administration Building, a marvel of holistic, high-tech design that was demolished to make way for a parking lot. The Larkin’s fate foreshadowed Wright’s appreciation for the car and the suburbs it underwrote. Both get their full due. The show delves deep into Wright’s plans for a new Baghdad, which melded a surprisingly tasteful appropriation of Mesopotamian design with car culture. There’s also a model of the unbuilt drive-through planetarium known as the Gordon Strong Automobile Objective, surrounded by a spiraling ramp for traffic: a sobering reminder that the Guggenheim’s design began with wheels in mind, not feet. Despite its dryness, the exhibition provides other timely reminders. Wright was a leader before LEED: his Taliesins are infused with a sense of place and local materials, while an expansive green roof sits atop a library for Baghdad. And his hope that people’s relationship to space could remake the fabric of society resonates in climate-changed, sprawl-conscious America now. The new president – also from Chicago – has said that had he not become a politician, he’d be an architect. And in a late interview, Wright struck an Obamaesque chord: “If I had another 15 years … I could rebuild this entire country. I could change the nation.” Fortunately for us, he didn’t do that. But from within his crowning work, we can appreciate the possibilities he opened up. If the exhibition feels more weak than it should, it also places an emphasis on the building itself. Just turn your back to the walls and walk to the railing, and you can see Wright’s stubborn determination to prove the primacy of architecture as what he called the “Mother-art.” Evidence of his impulse to make buildings religious and democratic places is on view too: all the other people who are doing the same thing, watching you, experiencing the building.

New rendering of Wright’s unbuilt mile-high skyscraper (image: Courtesy Harvard University Graduate School Of Design) Frank Lloyd Wright: From Within Outward is at the Guggenheim Museum, New York, until 23 August |

Words Alex Pasternack |

|

|

||