|

Aircraft hangar by Pier Luigi Nervi, 1940 (image: Riba Photographs Collection) |

||

|

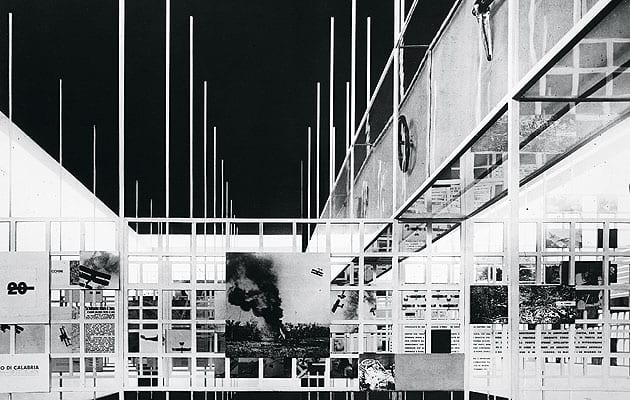

Modern architecture was fascist Italy’s way of pretending to be civilised – the result is an eerie collection of photographs, says Owen Hatherley. Modernism was the first form of architecture to be decisively shaped by the camera, to the point where, in the 1930s, architectural critics complained that buildings were being designed with the specific purpose of looking good in photogravure. And “classical” inter-war modernism, a Mediterranean world of white walls and blue skies, still has a grip on architectural photography: it is a permanently optimistic place where the sun is always shining and road signs, lamp-posts, adverts and, for the most part, people, are an irrelevant encumbrance standing in the way of the pure, Platonic forms. It’s rather apt, then, that this exhibition of photography should be centred on the architectural output of one of the 20th century’s most spectacularly unreal and deceitful regimes – Mussolini’s Italy. One of International Style modernism’s dirty secrets has long been the card-carrying fascist beliefs of architects such as Giuseppe Terragni. This exhibition shows how adroit the regime was at deploying modernism to put an elegant gloss on its brutality. The exhibition is divided into two separate rooms, one for Mussolini’s Italy, the other for the first two post-war decades. The former is the more interesting – these depopulated landscapes are bleak, but keenly seductive. Classicism and futurism are the poles of this aesthetic. Angiolo Mazzoni’s piazzas and arcades, which recall the paintings of Giorgio de Chirico, are exemplars of the architecture of death. The hangars and stadia of Pier Luigi Nervi might seem to promise something more dynamic. But that same funereal air is present in one of the exhibition’s most striking images – Ferdinando Barsotti’s symmetrical shot of Nervi’s Stadio Communale Giovanni Berta in Florence, its glazed tower enigmatically accompanied by the obligatory lonely human figure. Framing Modernism is packed with images and information, though it shows a certain timidity about telling a historical as well as aesthetic story. This is particularly true in the case of Giuseppe Pagano, the Casabella editor, architect and innovative photographer, who repudiated his fascist beliefs in 1943 by joining the Italian Resistance, and died in a Nazi concentration camp. Nonetheless, the images mostly tell their own story, particularly the postcards of Italian colonial architecture; modern structures which followed the bombs that rained down on Abyssinia. The relative conservatism of this exhibition hits you when you see a photograph of the 1934 Italian Aeronautical Exhibition. Its kinetic images of destruction in a constructivist-influenced space are most unlike the Estorick’s sober rooms. After the mayhem of the Second World War, the exhibition moves on to the years when Italy carved out a niche as world centre of “good design”. Many of the photographs are of boutiques, one with the name “Scandale” laid out in raffish neon. Again, there’s a sense of two modernisms, although this time the divide is between Milan’s gothic-futurist Torre Velasca and the svelte technocracy of the Torre Pirelli. The images here are a little livelier, less compulsive and strange than the earlier photographs, but the cities are still largely uninhabited, and the tone is still monochrome. The last photograph is Ugo Mulas’ Milan (1954). It’s completely unlike everything else here. Instead of standing elegantly alone among colonnades, people are talking, on their way home from work. In front of them are serried modernist blocks, shrouded in mist. Seldom has bad weather seemed like such a relief. |

Words Owen Hatherley |

|

|

||

|

Italian Aeronautical Exposition, by Edoardo Persico and Marcello Nizzoli, 1934 (image: Riba Photographs Collection) Framing Modernism: Architecture and Photography in Italy 1926-1965 is at the Estorick Collection, London, until 21 June |

||