|

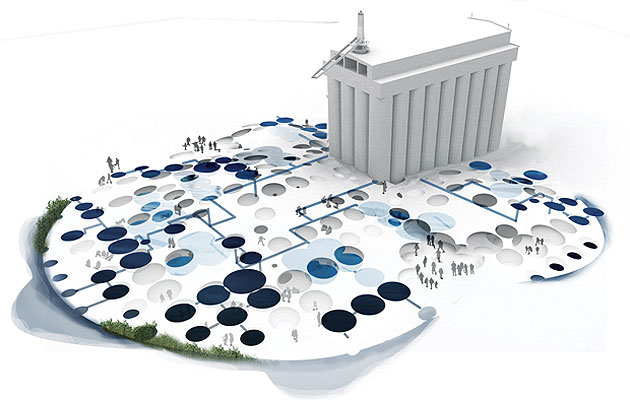

Victoria Soya Mills Silos in Toronto |

||

|

Forecasting how the weather influences architecture is, of course, unpredictable, says Steve Parnell Architecture has a tortured relationship with the weather: architects are far less interested in it than their photographers are. The weather is uncontrollable, contingent and doesn’t mediate well, which perhaps answers the question posed by Archigram’s David Greene: “If when it’s raining on Oxford Street the buildings are no more important than the rain, why draw the buildings and not the rain?” Buildings are necessarily left out in the rain. But architecture nowadays has less to do with buildings than with ideas, especially within education. Any studio project that concerns itself with weather is going to have difficulties precisely because the weather is something experienced, whereas architectural projects (as opposed to buildings) are merely seen. For instance, it’s very difficult to draw “pestiferous” humidity (as Reyner Banham referred to it in his Architecture of the Well-Tempered Environment). So co-editor Jürgen Mayer H’s students at the University of Toronto’s Faculty of Architecture were always going to have a tough time in their studio, upon which this book is based. The studio looked at the Victoria Soya Mills Silos on Toronto’s waterfront – impressive concrete structures that were long ago canonised into architectural lore through Le Corbusier’s Vers Une Architecture and of course much admired by Banham himself. But the results are the usual conjectural science fiction that has become the norm in M.Arch level architecture studios: something is in crisis, something has to be rethought, the students intervene and the resulting eye-candy changes the world – at least on paper. This “forecast” is the least interesting part of the book. The other two sections – the “report” and the “outlook” are worth more time because they don’t attempt to solve an artificial problem, they merely present an agglomeration of research on the weather that might interest an architectural audience. This is entirely in line with co-editor Neeraj Bhatia’s work as director of non-profit research collective InfraNet Lab, which concentrates on the research rather than the envisioning – an interesting direction for architects concerned more with ideas than the potential of what a slice of land and capital can offer. Bhatia’s short essay in the theoretical “outlook” section contextualises the studio from Corb to Banham to Koolhaas and seems too brief, leaving the reader wanting more. The “report” section starts with a brief history of “weather + science”, presenting the development of the understanding of weather, to its prediction and control. Chapters follow on “weather + war”, “+ health”, “+ tourism”, “+ media”, “+ shopping” and so on – all infogrammed for quick flicking. Some of it is painfully obvious, other nuggets are more valuable, such as Walmart’s use of private weather forecasting to benefit from Hurricane Katrina. Once more, it’s a shame there weren’t resources for more in-depth study – something like the Endless City by Ricky Burdett and Deyan Sudjic managed a couple of years ago. The chapter dealing with the weathering of materials deserves a book to itself. The big questions that are posed on the back cover, such as “is instability and disorder something that can be designed?”, are left open and suggest that a book such as this is the beginning of a much bigger reaction to the modernists’ paranoid insistence on control. My prediction is that there is a high chance of moderate to heavy scattered work on the interface between architecture and the weather to follow.

Pitter Patterns by Jürgen Mayer H Arium: Weather + Architecture, by Jürgen Mayer H and Neeraj Bhatia, Hatje Cantz, £32.50 |

Words Steve Parnell |

|

|

||