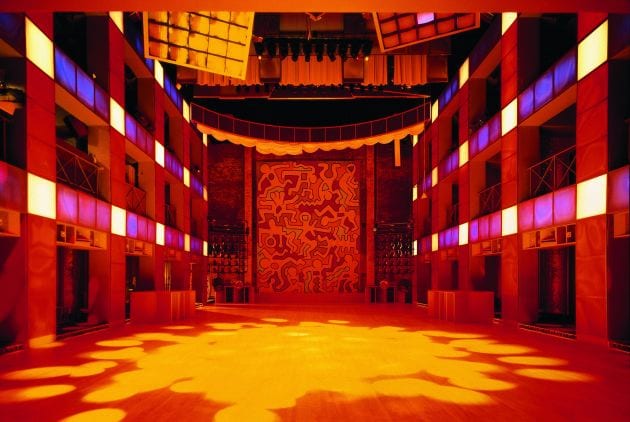

A giant Keith Haring mural looks down on the neon dancefloor of the Palladium, East 14th Street, on its opening night, 1985. Credit: Furudate.

A giant Keith Haring mural looks down on the neon dancefloor of the Palladium, East 14th Street, on its opening night, 1985. Credit: Furudate.

The wasteland buildings of 1970s New York, finds Ivan Lopez Munera, were re-activated by the human body. They became nightclubs and bathhouses for the emerging gay scene – and amid the sweat and steam was born an aesthetic that would change urban living everywhere

After the de-industrialisation of New York during the 1960s, it became known as a ‘disaster city’. But it was also a territory for experimentation in the construction of certain kinds of atmosphere. Space was cheap, thanks to the abundance of former industrial buildings for living, producing and exhibiting, giving rise to the SoHo loft movement. This was a game-changing situation in architecture and design, as Art Forum critic Nancy Foote explained in her 1976 article The Apotheosis of the Crummy Space. These places were not only important because of the redefined ‘beauty’ found in their industrial decay – pitted floors, crumbling plaster, exposed pipes, embossed tin ceilings – but also because of the freedom they gave one to interact with a narrative embedded in architecture.

It was in such spaces that an emerging form of political activism took place, as initially informal and discontinuous efforts to face the HIV/AIDS epidemic turned into regular meetings and actions by groups such as ACT-UP, Gay Men’s Health Crisis and Gran Fury. In a period marked by the Cold War, discos and saunas agglutinated a different kind of inhabitant. Mostly drawn from the LGBTQIA+, African-American and Latino communities, these were groups that were struggling to develop forms of resistance and empowerment that would make them more visible in the arena of US democracy. These club-goers were equipped to accommodate, through their bodies and their interactions, alternative forms of political action distinct from those of militarism, pacifism or civil protest. Going to a nightclub or a bathhouse was, in itself, a political act that had global repercussions in the years to come.

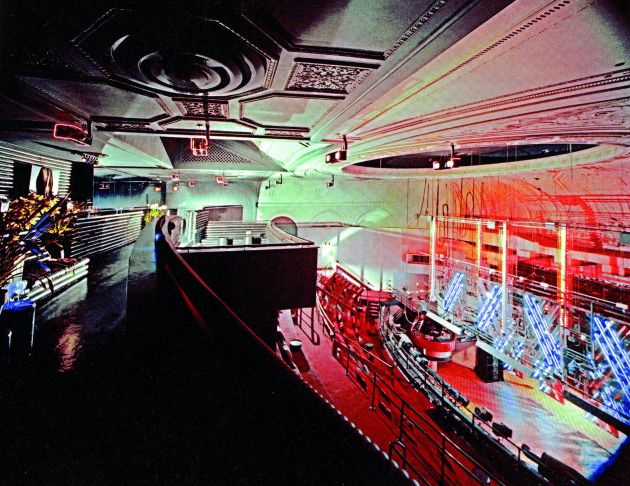

A view from the balcony to the dancefloor of Studio 54 at 254 West 54th Street. The building was originally the Gallo Opera House. Credit: Jaime Ardiles-Arce

A view from the balcony to the dancefloor of Studio 54 at 254 West 54th Street. The building was originally the Gallo Opera House. Credit: Jaime Ardiles-Arce

‘I got some friends but they’re gone, someone came and took them away, and from the dusk till the dawn here is where I’ll stay. Standing at the end of the world, boys, waiting for my new friends to come …’ The lyrics of the song Friends reverberated through the humid pool area of Continental Baths as Bette Midler sang them in 1971. It was part of her show The Divine Miss M, with Barry Manilow at the piano. As was usual at Continental Baths, the audience were mostly gay men in towels looking at the stage, looking at each other, or just looking. After all, this spot was, by the early 1970s, the perfect place to find friends. Any kind of friends.

Continental Baths, commonly known as the Baths or the Tubs, was a popular bathhouse located in the basement of the beaux-arts Ansonia building on the Upper West Side. Designed in 1899 as a lavish and self-sufficient residential hotel – with tenants including Stravinsky and Mahler – the Ansonia was equipped in its heyday with apartments, a ballroom, a central kitchen that served the units, its own farm on the rooftop and Turkish baths in its basement, among other features. The building was mostly abandoned by the late 1960s when its basement was rented by Steve Ostrow with the intention to create a fluid multi-sexual environment: Continental Baths. It was not until the Tubs ‘got into the disco business in 1970 that New York’s gay men actually had a space in the city that was unequivocally theirs’, wrote Alice Echols, a history professor at the University of Southern California in her book Hot Stuff: Disco and the Remaking of American Culture. It was opulent, with steam rooms, a restaurant, library, tanning booth, swimming pool, private apartments, television room and a dance floor. Nicky Siano, former resident DJ at Studio 54 recalled that ‘we were so chi-chi in our towels, cruising each other and slapping each other’s dicks … It was like a kind of orgy.’

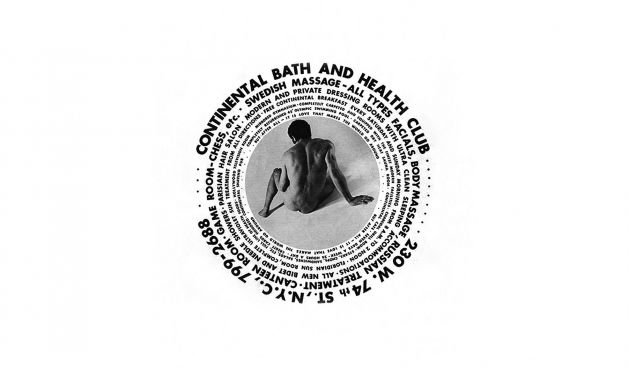

Advert for Continental Baths, a gay sauna in the basement of the former Ansonia hotel at 230 West 74th Street. Credit: New York City Archives

Advert for Continental Baths, a gay sauna in the basement of the former Ansonia hotel at 230 West 74th Street. Credit: New York City Archives

At a time when men-only spaces for dancing were still illegal, and New York legislation required clubs to have at least one woman for every three men, bathhouses created a friendly alternative under the guise of health or cultural facilities. They were an escape from the scrutiny of authorities and from homophobic attacks. Their distinctive character fostered a sense of community among their patrons. They were found all around the city: Everard at West 28 Street, St Mark’s in the East Village, Mount Morris in Harlem. In this landscape, Continental Baths reigned as the steamiest spot in town.

Diverse in their spatial organisation, the bathhouses in New York shared one distinctive architectural element: tiles. Considered a trademark, tiles were common because they were affordable, easy to find, maintain and replace, and came in a great variety of industrial models adjustable to any kind of architecture. They covered the locker rooms, the pools, the saunas and the corridors of these businesses in an infinite grid that promised another world and another future. Their clinical and shiny surfaces rejected the past, snubbing the possibility of stains or marks – or at least making them easier to clean.

The ‘flying ceiling’ at Studio 54. Jules Fisher and Paul Marantz designed the dancefloor, which was inspired by moving theatrical sets. Credit: Jaime Ardiles-Arce

The ‘flying ceiling’ at Studio 54. Jules Fisher and Paul Marantz designed the dancefloor, which was inspired by moving theatrical sets. Credit: Jaime Ardiles-Arce

In the 1970s, tiled rooms meant bathhouses. And no other architect used them as much as Alan Buchsbaum, whose apartment renovations became the subject of articles dedicated to his use of the material – ‘The Tile Alternative’ and ‘Tile’s New Horizons’ were among the headlines – and led to what came to be known as the loft style. As Buchsbaum once said, ‘Design is coming out of the closet if you like, or rather opening the closet door and revealing the contents.’ A river of tiles overflowed the closet door and connected the bathhouses with the interior renovations designed by his firm, Design Coalition. These included early designs such as the swimming pool of the Gerber House in Chapaqqua (1969) and his friend Bette Midler’s bathroom in her New York apartment (1981). He used not only the physical qualities of this material (affordable, low maintenance) but also its evocations (furtive and sexually charged spaces).

No Buchsbaum design explored the many possibilities of tiles more than his own apartment and office at 12 Greene Street in Manhattan. In 1976, he acquired with two friends, the artist Robert Morris and critic Rosalind Krauss – whose loft he later designed – a former manufacturing building in SoHo. The first two floors were owned by Buchsbaum: the ground floor for his office and the first floor for his apartment, the latter with an open mezzanine overlooking the former. For his own apartment (1976, renovated in 1982 and again in 1986 to add a steam room a few months before his death), he decided to use industrial- grade ceramic tiles to cover the corridor, the bathroom, the kitchen and even a plywood bed platform. The variety of the tiles was specified in every plan, drawing and draft of this project, not only in the apartment but also the office, with colours that went from oyster white to olive green, from turquoise blue to shiny black.

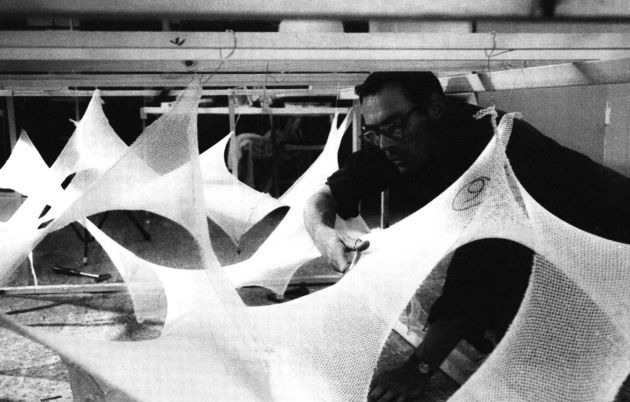

Working on the Electric Circus, 19-25 St Mark’s Place. The club, which opened in 1967, was designed by Chermayeff & Geismar. Credit: Don Davidson

Working on the Electric Circus, 19-25 St Mark’s Place. The club, which opened in 1967, was designed by Chermayeff & Geismar. Credit: Don Davidson

But the central element of this renovation was the bathtub, in the shape of a splash, at the very end of the ground floor and surrounded by a tropical garden, which was completely open to every visitor’s gaze. It was located in his office so that it was also visible from his bedroom via the tiled-covered mezzanine. The location of the tub was not only a cocky gesture but an homage to the bathhouses of New York as social centres. In the original plans, it is specified that the tub be at the ‘employees’ lounge’, the place shared by the office staff for lunch or breaks. It was not private, it was a place for gathering. As Buchsbaum pointed out: ‘Our whole feeling about nudity has changed. The rationale seems to be that if you’re friendly enough to live with somebody, then it’s not too far- fetched to bathe in front of them.’

The clandestine atmosphere of the bathhouses was mimicked by the serpentine glass-block wall that divided the bedroom and bathroom from a service corridor in Buchsbaum’s apartment. The shadows of people in one or other part of the wall were highlighted by the airport blue lights of the floor designed by Paul Marantz, who was also responsible for lighting schemes in New York nightclubs such as The Palladium, and were reminiscent of the sneaky views regularly enjoyed in saunas. The use of tiles, glass blocks and industrial lighting systems re-signified the materiality of these elements in invoking a complete urbanism, as did elements such as metro shelving, Russell & Stoll lamps, Edison Price voltage tracks and Mercury Circle line fluorescent lights, which were used all over Buchsbaum’s loft. His archives show an incredible number of receipts, invoices and credit lines in stores a couple of blocks from his house: the restaurant supply stores on Bowery and Pearl Paint on Canal Street. These elements and this urbanism, epitomised by the tiles, exploded in a series of renovations made by Buchsbaum for famous clients such as Diane Keaton, Ellen Barkin, Christie Brinkley, Billy Joel and Anna Wintour. The widely published images of these and other interiors would send the New York bathhouse style global.

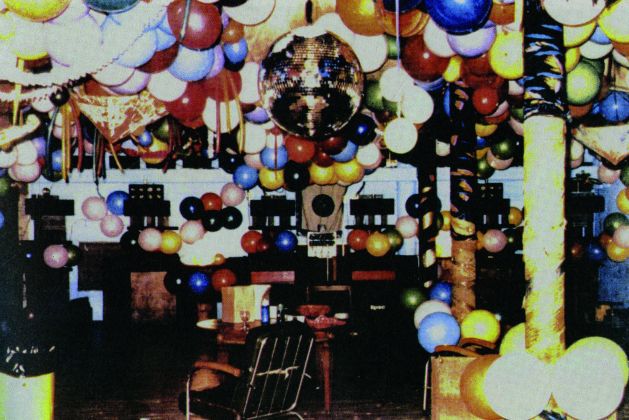

David Mancuso’s The Loft brought a different aesthetic to the New York club scene, with minimal lighting effects and no mirrors. Unknown photographer.

David Mancuso’s The Loft brought a different aesthetic to the New York club scene, with minimal lighting effects and no mirrors. Unknown photographer.

It was not by coincidence that the demise of the tiles in interior decoration and the closure of the New York bathhouses came hand in hand. In a 1981 New York Times article, a new epidemic – soon to be known as AIDS – suggested a relationship between the spreading of this ‘gay cancer’ (as it was then called) and the bathhouses. Doctors such as Yehudi M Felman of New York City’s Bureau of Venereal Disease Control, declared that the disease’s cause ‘could be the bugs out of the pipes in the bathhouses’. During the decade to come, most of the discos, saunas and bathhouses that operated in New York – among them Continental Baths – closed after New York State empowered local health officials to lock places where ‘high-risk sexual activities’ took place.

Buchsbaum himself succumbed to the epidemic just a couple of years later, on 10 April 1987. Two weeks after his death, a memorial was held at Metro Pictures in SoHo, near Buchsbaum’s loft and office. Bette Midler sang at it and remembered her friend; like her beginnings in the humid tiled rooms of the Tubs, she was ‘standing at the end of the world, boys, waiting for my new friends to come …’

This article appears in Icon 199, which explores the contemporary countryside.