|

|

||

|

There are 62 Lego bricks for every person on the planet, and that includes the one you step on with bare feet in the middle of the night. Another 564 bricks are manufactured every second. The brand is not only globally ubiquitous, it’s a serious industry – the company is also, for instance, the world’s largest tyre manufacturer. And the humble Lego brick turned 50 this year. The Lego company was founded in Denmark by Ole Kirk Christiansen in 1932. It made wooden toys and bricks, and became “Lego” in 1934, taking its name from “leg godt”, the Danish for “play well”. Christiansen learned of the possibilities of moulded plastic from a British salesman in 1947, and prototype plastic bricks were in production by the end of the 1940s. On 28 January 1958, after years of experiment, the company issued a patent for the “stud and tube” system that we all grew up with. Lego’s basic design has persisted, unaltered, since that day; bricks made in 1958 fit perfectly with bricks made today. All the different Lego systems – from Duplo for babies up to Technic for teens and engineering students – are compatible with each other. What makes the design so gratifying, however, is an incredibly delicate bit of engineering. Lego bricks are made of a kind of plastic called acrylonitrile butadiene styrene. They fit just right: bricks grip enough to hold together against gravity, but not so tightly that they are difficult to pull apart. To achieve this, they are moulded to a tolerance of just two microns – two one-thousandths of a millimetre. Not that the millions of children (and adults) who play with Lego bricks have to appreciate that in order to enjoy the experience. They just like the unlimited potential that comes with even the most basic set of bricks. According to the Lego company, there are more than 915 million ways of combining six basic eight-stud bricks of the same colour. And the adults who “play” with Lego aren’t just hobbyists – Lego models seem to have become an ironic fixture on the international biennale circuit. All memories of real, devoted play with Lego are tinged with pain. There’s some mortification of the flesh that comes with childhood Lego devotion: sifting through the bricks for hours made the fingertips red and sore. Joints would seize up after sitting cross-legged on the floor in intense, meditative concentration. The sharpest torture was mental, though. It came with the discovery that there were not quite enough white bricks to complete the ground floor of the building you were working on, or that the elaborate assembly of Technic gears that you had just spent all Saturday putting together locked up, rather than running smoothly. These grim moments were often followed by the question, “How can I get this to work?” and a bout of junior troubleshooting. This problem-solving was driven by a desire for the Lego toy that one had mentally sketched out, not for the joy of fixing for its own sake. But Lego did teach that the journey to the toy pictured on the box was at least half the fun. Airfix might have been similarly educational, but once modellers had put the final touches on their scale Spitfires, they didn’t then dismantle them to see what else the parts could make. With Lego, the parts are worth more than the whole. However, the strength of Lego is also its weakness. If you had enough bricks, you could build any model you saw without buying new sets. Lego was essentially equipping children with the tools to pirate its own product. So in order to stay in business, the company must endlessly bring out new ranges of themed and branded Lego. This pollutes the concept that you can build anything with the simplest bricks, and your imagination will do the rest. But if Harry Potter Lego is the price of keeping this perfect toy in production, then so be it. |

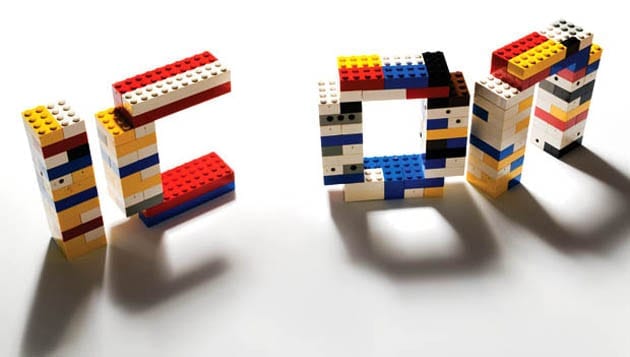

Image Andrew Penketh

Words William Wiles |

|

|

||