The Planta Solar 20 power plant near Seville, Spain. PS20 produces electricity with large movable mirrors called heliostats. Alamy.

The Planta Solar 20 power plant near Seville, Spain. PS20 produces electricity with large movable mirrors called heliostats. Alamy.

As climate catastrophe looms, the interdependence of the urban and rural worlds has never been starker. The countryside can no longer be dismissed as a bastion of tradition – it is where the future is taking place, finds Edwin Heathcote.

The great false dichotomy of modernity has been the notion that the city and the countryside are somehow in opposition, things distinct and apart. There is, of course, only one landscape and that is the landscape of capital. Or we might say, the landscape of humanity.

The spurious quest for some kind of authenticity in the rural, for roots and traditions that might somehow anchor humanity within an ancestral continuum, has been a boon for fascists and madmen who position globalisation as the villain when, clearly, it is the idea of unending growth itself that has always been the problem. Pol Pot attempted to re-ruralise Cambodia, which led to an unparalleled disaster, and Mao’s cultural revolution was anti the urban intelligentsia while lauding the peasantry, and also ended in mass incarceration and starvation.

Impending climate catastrophe is, however, refocusing minds on the countryside in unpredictable and often fascinating ways. With bush fires raging across Australia, the Bolsonaro government tearing through Brazil’s Amazon rainforest, the accelerating disappearance of permafrost and the melting of glaciers, as well as fears about the effects of eating meat and genetic agriculture, the countryside has been transformed from the locus of stability to the source of panic.

Stop City (2007-08), Dogma’s critique of over-urbanisation, part of Sébastian Marot’s exhibition Taking the Country’s Side: Agriculture and Architecture, Lisbon, 2019. Image: Dogma.

Stop City (2007-08), Dogma’s critique of over-urbanisation, part of Sébastian Marot’s exhibition Taking the Country’s Side: Agriculture and Architecture, Lisbon, 2019. Image: Dogma.

A radical shift in contemporary consciousness has led us to miss the key transformations of the last few decades. Partly thanks to architects and academics like Rem Koolhaas, we have been seduced into thinking that the city is not only the zenith of culture but the main event. But now, in a very Koolhaasian gesture, Rem is waving at us from the sticks, shouting ‘Hellooo – I’m over here’. The new exhibition at the Guggenheim, Countryside, The Future, which he devised with Samir Bantal, director of AMO, is a single, perhaps significant shot in a broader cultural reassessment of the rural. It unfolds in Manhattan’s most urbane setting, but then, if it was in the countryside, no-one would go and see it. Which is, of course, part of the problem.

The rural vote for Brexit in the UK, including from farmers dependent on EU subsidies and trade with Europe, and for Trump from the (heavily subsidised) rural US, have highlighted the growing gulf between the inhabitants of the countryside and the city. They might also lull us into thinking the two are somehow discrete. Koolhaas suggested to me two years ago that he was inspired to study the countryside by the discovery that his neighbour at his partner’s former house in the Swiss countryside was not a stout local farmer, with his work clothes, shovel and cap. Instead, he turned out to be a nuclear physicist. The countryside is no longer teeming with place-bound peasants but with seasonal immigrant workers and urbanites in their holiday homes. In many cases, they have made those homes so desirable and expensive that country dwellers find themselves unable to stay.

Nithurst Farm, South Downs National Park, by Adam Richards – part of an intriguing new wave of contemporary rural British architecture. Image: Brotherton Lock.

Nithurst Farm, South Downs National Park, by Adam Richards – part of an intriguing new wave of contemporary rural British architecture. Image: Brotherton Lock.

Agriculture is itself unrecognisable compared with its one-time (self- proclaimed) bastion of conservative tradition. It is now a high-tech industry employing fewer and fewer people and more machines. There are self-driving, GPS-guided tractors and combine harvesters, robots tending crops in polytunnels and automated irrigation systems producing every non-native crop imaginable. There are massive, mechanised poultry farms and slaughterhouses and piggeries capable of polluting rivers and coasts for hundreds of miles. And there are masses of unlucky cows sheltered from anything approaching nature in steel structures, unsettling methane-fearing activists with their incessant farting.

In architecture, against the received wisdom, the countryside has always been the locus of experimentation and influence. In our city-obsessed era, we might believe that architecture is a metropolitan elite concern but historically, many of the most influential buildings have emerged in the country, while architects have identified rural building types as the progenitors of modernity. Think of the Palladian villa, which became the model for the English country house and, ultimately, the modernist villa around which so many of our notions of a desirable dwelling still revolve. Sébastian Marot’s smartly titled Taking the Country’s side: Agriculture and Architecture at the Lisbon Architecture Triennial last year highlighted some of the critical exchange from rural to urban, from the speculative origins of the Greek temple in the stone granary to the inspiration Le Corbusier, Gropius and others drew from the great grain elevators and silos, water towers and agricultural mega-structures of the early 20th-century US.

Brown sugar production facility in Xing village, China, designed by Xu Tiantian’s practice DnA in 2016. Photo: Wang Yiling.

Brown sugar production facility in Xing village, China, designed by Xu Tiantian’s practice DnA in 2016. Photo: Wang Yiling.

Frank Lloyd Wright, designer of the Guggenheim, where the Countryside exhibition is showing, disliked the city. He attempted to create an architecture rooted in the American landscape. The so-called radical architectures of the post-war period – the batty, the hippy and the techy, from Ant Farm and Paolo Soleri to Superstudio – built or envisaged landscapes in the countryside which adopted some aspects of the urban but were essentially other, drawing their surrealism from their isolation within rolling landscapes – just think of Superstudio’s endlessly reproduced grids.

You might credibly argue that the most intriguing architecture of today is also emerging in (if not actually from) the countryside. Certainly the best designs in British architecture are currently rural. Architects such as David Kohn, Stephen Taylor, Adam Richards and Invisible Studio are re-examining the form and language of the rural house in a way that has not happened in perhaps two generations. Of course, all this obscures a bigger picture in which housebuilders, their bonuses and stocks hyper-inflated by incompetent government housing policies, are keenly eyeing green-belt land to carpet with their customary car-dependent, derivative, tarmac-covered blandscapes. Nevertheless, the rural has once more become a site of significant design.

The Westland has been the Netherlands’ main greenhouse horticulture region since the 1880s. Image: Luca Locatelli.

The Westland has been the Netherlands’ main greenhouse horticulture region since the 1880s. Image: Luca Locatelli.

Nowhere is this clearer than in China where the state, after decades of concentrating on the explosion of entire tiers of new cities, has refocused its attention on the denuded and depopulating countryside. It is supporting schemes to rebuild communities and industries and some of these appear truly remarkable, although it is never quite clear how much is propaganda and how much is driven by a real desire for change. Xu Tiantian’s village regeneration project, based around a revived brown sugar production facility in Xing village, is exactly such a design. Although it captures China’s abiding quest to root its real culture in the rural, it is ultimately more like a tourist wellness resort than a genuine attempt at rethinking a countryside economy. Its architecture is sophisticated and seductive, yet is this not just another fetishisation of an outmoded image of the countryside? Post-Mao, China still supplies an intriguing model for the countryside. It is illegal to own agricultural land, so all farms are owned collectively or by the municipality. It could have been a model for a new collective commons, but the attraction of China is waning as its surveillance-state model palls.

Perhaps it is inevitable that in the West, the countryside is being turned into a playground for the urban elite. Perhaps it always was that way, from the Romans with their villas and the English with their country houses to the Russians with their dachas, but the locus of capital has been transformed. The great estates once drew their wealth from agricultural production, and their owners built themselves fashionable footholds in newly prosperous cities. Now agricultural production is split between corporate agribusiness and subsistence smallholders, subsidised by governments based in the capitals. A fascinating new component is the manner in which the sovereign wealth funds of authoritarian governments from China to the Gulf are buying up agricultural land from Scotland to Africa, preparing for future scarcity. The countryside still provides our food but we are probably paying too little for it, in terms of money, and attention.

Inside the Koppert Cress greenhouse facility in Monster, Netherlands, red LED lamps promotes growth. Image: Luca Locatelli.

The new industry has also rooted itself quietly in the countryside, albeit with a gentle thrum. It can be hard to distinguish the principle typologies of modern rural architecture – the distribution shed, the animal battery farm, the freeport, the assembly plant and the data centre. Their architecture – the real new architecture of the rural – tends to be defined by shallow pitches and corrugated metal, grey relieved by small flashes of primary colour, unbranded, undistinguished, unwilling to draw attention to itself and always leaving a wide security perimeter and plentiful CCTV cameras because something societally suspect or unsavoury is going on inside. It is an architecture of secrets, the opposite of the architecture parlante that the visionary French architects of the 18th century, Claude Nicolas Ledoux and Jean-Jacques Lequeu envisaged for the countryside. It is an architecture of silence.

The new industry of the countryside is the harvesting of data. New sheds in the Nevada desert or the Irish countryside represent a post-human architecture, an architecture not designed for people to populate yet still intimately involved communications into informational and behavioural surplus. The server farms and data centres are mining our lives, extracting information. Inside they glow with an eerie light designed not for humans but for machines. The Tahoe Reno Industrial Centre is, for instance, a colossal, 430sq km site housing data sheds and distribution centres serviced by five power plants and is also the future location of Tesla’s battery gigafactory.

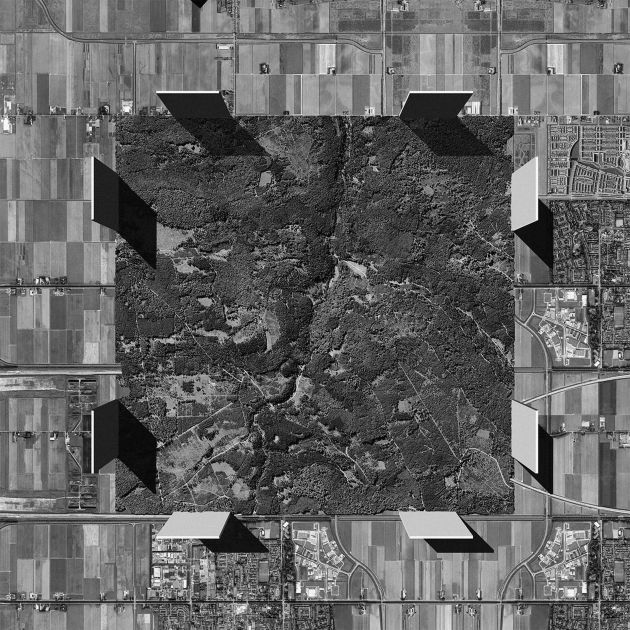

Data farming: Silicon Valley from Mission Peak Regional Preserve, Fremont, California. Image: Yuval Helfman / Alamy.

Data farming: Silicon Valley from Mission Peak Regional Preserve, Fremont, California. Image: Yuval Helfman / Alamy.

Agriculture is itself going the same way. Hydroponic greenhouses are designed for automated systems in which even the picking is robotised. Internal lighting is designed for plants not people, permeated by the odd glow of strange spectra. The new rural architecture is a cocktail of post human and post agricultural, with barns and farmhouses turned into holiday lettings, the landscape turned into a leisurescape to simulate the natural, and the practice of actual agriculture by now so industrialised it is almost unrecognisable. The countryside is being consumed. California, once the site of the citrus boom, is now the site of the digital bonanza while the deserts around it, in Nevada and beyond, accommodate its massive appetite for data.

The countryside suddenly finds itself at the heart of the debate about the future. With huge areas of what was once permafrost thawing and rapid changes being wrought through fire, drought and destruction, it is changing faster than ever and is becoming a new frontier for design. But all of that is to ignore the fundamental lesson of the last half century, that there is no real distinction between city and country. Most of us live in suburbs, in an in-between world approximating a vague reminiscence of the rural, and it is in these blurred boundaries where growth is taking place.

There is no distinction because there is only one planet. Whether it is a self- regulating Gaia-like system, a sentient organism or a simulation created by a super-sophisticated future AI, we are all on Earth and the future of the green parts of the map will affect all of our futures. If indeed, we have a future at all.