|

|

||

|

Is it just us or is the young architect a very different beast these days? For the first time, “young” actually means young, but “architect” may no longer mean architect. This is our list of the most significant rising practices. Like all list stories, you’ll disagree with some of it, but that’s half the fun. The first thing to mention is that the “young architect” is definitely younger than he or she used to be. We borrowed the convention of using 40 as our cut-off point, but at least half of the people on this list are 35 or under – and one of them is a 33-year-old overseeing a practice with 75 staff. Have we moved from the architect of promise to the upstart with power? Secondly, the school of thought that architects need to build things to make their presence felt is losing currency. There are a few on this list who reflect that – these are the strategists and networkers who challenge legislation and foment debate. But where’s all the rebellion? There’s little sense here of a generation reacting against the ideology of its elders – perhaps that’s simply because we live in apolitical times. In fact, there are few signs of a coherent generation at all, although there are definite camps: the Children of Rem, the quiet but extremely sophisticated disciples of Zumthor and SANAA, the tower builders and the open-network activists. This is a global list in more ways than one. You’ll find three Americans, two Japanese, two Chinese, a Chilean, an Indian and a bunch of Europeans. But increasingly these practices are international anyway, undermining notions of national architecture – more important a crucible these days are the practices they meet at. Having said that, you’d think a British magazine might put more British architects on the list. But then, the key thing that is giving all these youngsters their big break is the culture of open architecture competitions – and that’s something this country desperately needs. REX

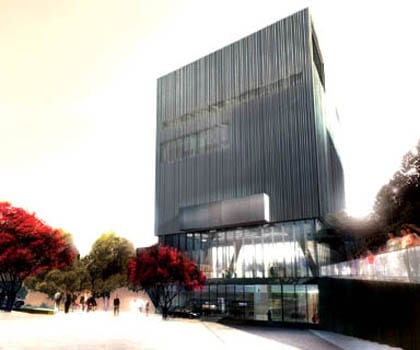

“We’ve made a recent rule: we don’t talk about OMA anymore,”says Joshua Prince-Ramus, co-founder, with Erez Ella, of REX Architects. The practice, which used to be the New York branch of Rem Koolhaas’ Office for Metropolitan Architecture, seceded in 2006 in what was effectively a bloodless trans-Atlantic coup. Prince-Ramus and Ella went with their mentor’s blessing, apparently, but their relationship to Rotterdam is still a sensitive subject. REX, it has been frequently pointed out, did not have an average start in life. Young American practices have few challenging outlets: a loft conversion here or a beach house there. As part of the most reputable practice in the world, REX cut its teeth on the design for the Seattle Public Library, one of the most important pieces of American architecture of the new century. Now independent, these 30-somethings have huge civic projects on the go, and so it’s fair to suggest that they were springboarded into the big time. “That’s a strange way of putting it,” says Prince-Ramus, in his office overlooking Manhattan’s West Village. “That if you don’t suffer you’ve had an unfair advantage.” In a tight black T-shirt, Prince-Ramus cuts the figure of the varsity jock. He is the front man – the talker – while Ella is quiet and watchful. They are architects with a very clear agenda, a mission almost, and that is to make the profession relevant again after what they see as years of marginalisation. “It’s our own damn fault,” says Prince-Ramus. “Architects have become stylists, people who do window dressing. We’re taught to say ‘that’s my vision’, and the client says ‘but that’s not what I need’. Meanwhile, all the important stuff that has a moral or social agenda, we have no involvement in anymore. That gets carried out by developers.” Their solution – one born of America’s conservative, risk management architectural climate – is to become tough, Machiavellian businessmen. They talk in terms of “liability”, “control”, “negotiating hard on contracts” and above all, putting the client’s needs first – “Once you do that, the client’s totally fine to be pushed way outside of their comfort zone.” This is the stuff, they feel, that architecture students need to be taught, not deconstructivist literary theory. A true child of OMA, REX specialises in identifying and then distinguishing a building’s different programmes. They call it “hyper-rationality”, which clearly suggests a functionalist, or performance-based, logic at the expense of anything else. In the vast and controversial Museum Plaza scheme in Louisville, due to complete in 2010, residential, business and cultural elements are all separated and piled on top of each other in what appears to be a precarious stack of skyscrapers. The interesting, and perhaps ironic, thing is that this hyper-rationality (as in the Seattle library) produces a form that is even more iconic than your average aesthetically minded icon. Its clunkiness has a kind of anti-aesthetic far more powerful than mere elegance. Picturing cities full of this stuff is scary. But REX is super-ambitious and driven, and with a large project finishing in Turkey this year and Louisville in two years it has momentum and, almost certainly, staying power. JM

ALEJANDRO ARAVENA “It’s a social and political problem, but we can use design to address these issues,” says Aravena. Elemental’s projects work within tight policy restrictions and with few resources. The idea is to provide a set of conditions that allow the building units to be adapted and increase in value over time, redefining social housing as an investment not an expense. “I have the luxury of operating, and being trained, in the third world,” says Aravena. “I can afford to be primitive enough.” This sense of the primitive, of boiling a design down to its most relevant and irreducible essence, runs through the work of his private practice, including several widely acclaimed buildings for Santiago’s Universidad Católica. These works attempt to “move backwards rather than forwards”, reflecting the basic values of informal education. Aravena, who has held visiting professorships at Harvard and the AA and is widely published, is currently applying his disciplined approach to a children’s education centre for Vitra, to sit snugly between Zaha and Siza in Weil-am-Rhein. “I’m trying to be cutting edge. It’s more like what architects are expected to do.” OW

ONE TO WATCH: STUDIO EBV EBV’s design process is a slow and careful one. “We always start with the same thing, with pencils and models,” says co-founder Alberto Veiga. “We can’t work in any other way. The computer models all come later.” FAT Well, for one thing, FAT is a perpetual slap in the face of the polite neo-modernism that characterises the mainstream of British architecture. At the same time, it renounces the mouse-happy swoops of the digital revolution. The natural successors to Venturi Scott Brown and Michael Graves, this practice is pursuing an alternative route populated by follies and tinged with eccentricity and nostalgia. “It’s about communication,” says co-founder Sam Jacob. “We want to make architecture that’s engaged as a cultural activity – we’re not interested in form-making or exploiting technology.” Playful and irreverent, FAT’s work avoids the academicism of so much earlier postmodernism. This is a practice immersed in popular culture – from football to children’s TV – with a conversational talent for shooting down pretension with a witty lowbrow reference. The writing and teaching of all three members – who are currently spreading the word as visiting professors at Yale – ought to be influential. And for a local institution, they’re still surprisingly young. JM

JESKO FEZER His work with the Institute for Applied Urbanism produced a subtle and beautiful intervention for Palais Thinnfeld gallery in Graz last year. Through his work with An Architektur magazine, Fezer organises Camps for Oppositional Architecture – a conference of around 250 architects exploring interventionist tactics. He also manages to co-run the independent bookshop Pro qm in Berlin and a seven-inch record label, and he teaches and exhibits. All of these activities are related to architecture, but they aren’t traditional role of an architect. Fezer might be the name on this list, but his work describes the versatile practice of a multitude of independent architects working outside the traditional boundaries of a one-name office. Of course, you might never have heard of them as individuals, but this is design beyond authorship and makes it all the more interesting. CC

BIG The dotcom boom might have had something to do with it, muses the effervescent Ingels, 33, who left his post at OMA to co-found Plot with Julien De Smedt when they were 25. “19-year-old programmers were becoming billionaires overnight and Frank Gehry had invented the icon,” says Ingels. “It seemed totally possible for us.” The genesis of one of the most hotly tipped young practices in Europe was intriguingly not in architecture, but in film. The friends applied to fund a movie and did a few architecture competitions on the side. “After six months we had won three competitions in a row and we got a ‘no’ for funding for the movie,” says Ingels. “So we became architects.” Then followed five years of remarkable success. Plot captivated the architectural public in Europe, winning both competitions – for social projects such as public housing and a psychiatric hospital – and awards by the armful. However, the practice split acrimoniously in 2006. While his former partner De Smedt works across the world, Ingels is happy to concentrate his energies on Copenhagen. “There is an entire side of architecture that is strategic, which is easier to do in places where you have intimate knowledge, where you can be cheeky.” Strategically, BIG is doing well. The major projects in the office are four towers in Copenhagen of up to 180m. At the moment there is a 45m height limit in the city but there is a political pressure to densify, and the office is waiting for the mayor’s decision. Other projects on the go are a hotel in Sweden, and – a recent major coup – the Copenhagen Maritime Museum competition, a project Ingels describes as the anti-icon, a hole in the ground. His manifesto, entitled, BIGamy, is about resisting “conceptual monogamy” to ideas: “Rather than being radical by saying fuck the establishment… we want to try to turn pleasing into a radical agenda.” In principle, he is saying that rebelling is useless, as the existing system is the result of a series of rebellions. What good would another revolution do? His solution is to be everything to everyone. It’s a pretty savvy bit of business rhetoric, and also a clear sign of the influence of Ingels’ time at OMA. Despite the bright colours, the persona, the graphics, his approach to architecture boils down to Occam’s razor: the simpler the object and clearer the derivation of the idea, the better. In other words, if it’s not memorable and it’s not easy to understand, it’s not there. “People do get excited about good ideas. If your ideas start with something people can relate to, not like French philosophy or Jewish mysticism, but if they’re about football fields and affordable homes and parks, people get it. And they like it if they get it.” BG Image Dominik Gigler

ARCHITECTURE FOR HUMANITY Based in San Francisco, AfH celebrated its 100th project last year (compared with just seven projects two years ago) and is estimated to have helped around 14,000 people worldwide. Projects range from housing for Hurricane Katrina victims in Biloxi, Mississippi, to tsunami resettlements in Moratuwa, Sri Lanka. Born in London, it was Sinclair’s postgraduate studies at the Bartlett that inspired him to leave for the USA. While his classmates were busy designing signature buildings, Sinclair developed a shelter for New York’s homeless. His tutor asked him to resubmit his drawings, saying his work was too depressing. “I bought a one-way ticket to New York and left, overnight,” said Sinclair in an interview with icon last year. In March 2007, Sinclair launched the Open Architecture Network (OAN), which offers free construction blueprints of AfH’s best (and worst) projects. “The whole network is based around the lessons we’ve learned over the last nine years. We don’t want other people to have to learn them – we’ve made those mistakes.” Sinclair has won numerous awards for his work, including the prestigious TED award in 2006. He recently launched the AMD Open Architecture Challenge, offering $250,000 towards the construction of computer labs for Kenya, Nepal and Ecuador. The winning designs will be announced in April 2008. CM

ONE TO WATCH: SERIE

|

Words Justin McGuirk + Beatrice Galilee + Céline Condorelli + Julian Worrall + Oliver Wainwright + Christine Murray |

|

|

||

Joshua Prince-Ramus (left) and Erez Ella

Joshua Prince-Ramus (left) and Erez Ella Museum Plaza, Louisville

Museum Plaza, Louisville Dee and Charles Wyly Theatre, Dallas

Dee and Charles Wyly Theatre, Dallas Vakko headquarters, Turkey

Vakko headquarters, Turkey The CITEDUC centre for digital research and technology at the University of Chile, Santiago, 2006. Image Cristobal Palma

The CITEDUC centre for digital research and technology at the University of Chile, Santiago, 2006. Image Cristobal Palma

The Sint Lucas Art Academy, Boxtel, 2006. Image Johan Van Gemert

The Sint Lucas Art Academy, Boxtel, 2006. Image Johan Van Gemert Image Michael Maier

Image Michael Maier

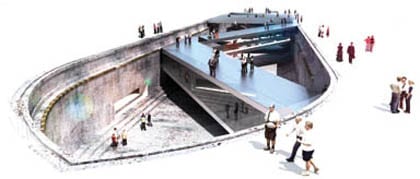

Copenhagen Maritime Museum, an “anti-icon” in a dry dock, due in 2010

Copenhagen Maritime Museum, an “anti-icon” in a dry dock, due in 2010 VMCP hotel in Stockholm, due in 2010, which has an image of Sweden’s queen in the façade

VMCP hotel in Stockholm, due in 2010, which has an image of Sweden’s queen in the façade BIG House, Copenhagen, due 2009

BIG House, Copenhagen, due 2009 AfH stepped in during the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina

AfH stepped in during the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina