|

|

||

|

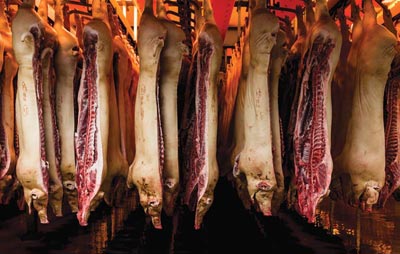

Slaughterhouses are meant to look anonymous, so rarely is much thought given to their exterior design. Yet those assembly lines of suspended carcasses played a fundamental role in the grisly birth of modern architecture Death’s taste in architecture is unfussy. The Meat and Livestock Commission’s Slaughterhouse Design Manual, an otherwise comprehensive and fastidious document, refers only twice to the envelope of the buildings it describes, once to state that it “need not be elaborate”, and again to allow: “It must be stressed that there is no ‘standard’ solution for the building shell.” Generally, though, the humble steel-framed “portal” style of building – in other words, a typical agricultural or industrial shed – is preferred. No need for a reprise of the debate over whether architects should design prisons. Here, the question never even arises: architects are simply not needed. “Modern practice favours no windows,” the Manual states bleakly. The anonymous shed’s anonymity is derived in part from its ubiquity. It is the opposite of rare; it dominates agriculture, industry and logistics. As Paula Young Lee points out in her introduction to Meat, Modernity and the Rise of the Slaughterhouse, a 2008 cultural history of the abattoir, there are plenty of infrastructural buildings that are “culturally suppressed as embarrassing necessities, massive in scale but without symbolic monumentality” – sewage farms, for instance. “Among this sordid group, however,” Lee continues, “the slaughterhouse is especially reviled, for its sole purpose is to kill, producing serial death as well as saleable meat.” She quotes a Napoleonic code governing abattoir construction: the buildings “must be solid and no more, in order to avoid high costs, and they must be completely removed from all ambitions to architecture and ornamentation”. Our Slaughter-House System, a 1907 polemic by C Cash, arguing for bigger, purpose-built facilities in which to kill animals, also devotes little thought to how a slaughterhouse should look like from the outside. It depicts a number of model examples from Britain and Germany, none of which look much different to other civic institutions of the era: they could be public baths, army bases or asylums. Cash’s main concern is hygiene, and so his chief exterior recommendation is that the buildings be “in an isolated position”, as opposed to the “insanitary structures stowed away in the courts and alleys of our great towns”. A hundred years later, the Slaughterhouse Design Manual echoes the recommendation, proposing sites away from housing and industrial land. Its suggested site layout is screened by fences and walls, with the less conspicuous “clean” end – where the processed meat emerges – nearest the road, and the “dirty” end – where the still-breathing animals enter – at the rear. It is a place to be ignored – an inverted monument, an anti-landmark. Inside the artless, anonymous box, the spaces and processes of slaughter offer a macabre lesson in design. They are subject to continual innovation and refinement, but also show the limitations of design. They have, in many fundamental respects, remained unchanged since the 19th century. And the most fundamental feature that remains unchanged is something that can never be refined away or replaced by a half-measure: they are places of bloody death. Before we go further, Reader, you have been warned.

The last space that livestock experience, the beginning of their end, is called a “lairage”; the terminology of the abattoir is surprisingly free of euphemism, and its occasional moments of semi-quaint ruralism (drovers, stickers) are rare amid the general candour (blood trough, scald tank, gut room). Animals arrive by lorry and are organised in the lairage. One by one they progress to a “stun pen”, where a slaughterman called a “knocker” deals a blow to the head. A side door then opens and the animal slumps sideways on to a ramp called a “dry landing area”, where they are suspended by the legs. The floor of the stun pen has been the subject of much thought. Often it will be shaped into a shallow step or slope, so that the animal’s legs are lower on the side of the discharge door; its balance point is thus moved slightly to one side. “For the animal it is no worse than standing on uneven ground,” the Manual says, “but it has the advantage that when the animal is stunned and the door opens the carcase rolls out quickly and cleanly.” The author acknowledges that some welfare groups object to the animal spending its last moments of consciousness slightly off-kilter, but here, as throughout, the Manual pragmatically weighs different kinds of cruelty against each other, and argues a swift fall is best, in order to minimise the time from “stun to stick”. The stick is the point of slaughter itself. The “sticker” stands on a platform and cuts the throat of the suspended animal. It takes about 30 seconds for it to bleed to death. The carcass then proceeds through the slaughterhall on the slaughterline. (From here on, the word “slaughter” shows a grim talent as a prefix.) Almost entirely bypassed by architecture, you might expect the slaughterhouse to be bypassed by architectural history. But it isn’t. In fact the evolution of the slaughterline gives the abattoir an important part to play in the history of modernity, a role first described by the architectural historian Sigfried Giedion in his seminal “contribution to anonymous history”, Mechanization Takes Command.

Giedion’s intention in this sprawling and fascinating book was to trace the impact of the coming of the machine through the way it shaped the mundane things around us – which in turn have shaped us in unremarked but fundamental ways. “The sun is mirrored even in a coffee spoon,” Giedion wrote. “For the historian there are no banal things.” As mechanisation entered the production of meat, it encountered problems. Before Chicago’s fabled Union Stock Yards rose to eminence and infamy, Cincinnati was the USA’s slaughter capital. Giedion describes the hundreds of patents issued in that city to automate and speed parts of the slaughtering process. Many resemble the sickening “harrow” from Franz Kafka’s Penal Colony – for instance, a terrifying machine that dragged fresh-killed pigs through a ring of scraping blades mounted on tightly sprung arms, ostensibly giving it a clean, close shave. What united all these instances of ingenuity was failure. “They did not work,” Giedion wrote; “In the slaughtering process the material to be handled is a complex, irregularly shaped object: the hog. Even when dead, the hog largely refuses to submit to the machine.” Humans could not be removed from slaughter – one senses a kind of cosmic justice there, that we are unable to turn the process over to a whirring box – and the implications of this failure of mechanisation were far-reaching. “For the speeding of output there was but one solution: to eliminate loss of time between each operation and the next, and to reduce the energy expended by the worker on the manipulation of heavy carcasses.” The slaughterline was created, with animals hooked onto pulleys and rails to be pushed between workers, each of whom specialised in a specific task. This was the birth of the modern assembly line, and thus of modernity itself. In Chicago, the boundless West and its vast herds led to the immensity of the Union Stock Yards, where mass production of meat dwarfed anything attempted in Europe before or since. The Illustrated History of the Union Stockyards, with Humorous Stories, written by W Joseph Grand in 1896, is a boosterish description of the Chicago yards at their peak: a landscape covering thousands of acres, including 50 miles of streets and alleys and hundreds of wooden pens that could accommodate 50,000 cattle, 200,000 hogs, 30,000 sheep and 5,000 horses at any one time. The 15 packing houses were multi-storey, and livestock entered at the top, via a huge network of sloping wooden viaducts, “which are in strength if not in beauty fine examples of the builder’s skill”. Here, “much of the live-stock from the yards is transformed from lowing cattle, bleating sheep and grunting swine into neatly canned dried beef, luncheon meat, potted tongue, minced collops, breakfast bacon, deviled ham, ‘condensed’ soup, and the thousand and one other delicacies undreamed of by our grandmothers, but which are revolutionizing domestic economy as surely as electricity is working a revolution in mechanics.” The stunning and throat-cutting took place on the top floor, and gravity assisted the rest. At this point, Grand’s hearty good cheer falters. Daily there are scenes “which would almost convince the most callous that killing animals for food is, after all, little short of cannibalism”, and “many visitors faint”.

Still, he assures the reader, the methods are as humane as possible, and “not a speck of dirt reaches the meat”. Here, Grand is being thoroughly dishonest. A decade later, the investigative journalist Upton Sinclair would publish The Jungle, a stomach-churning exposé of life in the Union Stock Yards, which taints the reputation of the trade and the city to this day. Specks of dirt were the least one could expect: diseased animals and even the body parts of injured workers were going straight into the meat supply. Cash, writing in Britain a year later, refers to “American meat horrors” as something on a different plane altogether to European practices, however inadequate those might be. “[T]he American meat-factory is in no sense an abattoir,” Cash claims. “The abattoir has, indeed, for its essential object the prevention of those very abuses which have made the American meat-factory a byword in the civilised world.” Nevertheless, the slaughterline developed in Cincinatti still runs through the abattoir. After bleeding, the animal is beheaded, its feet removed, and it is skinned and gutted. And the slaughterline runs, hidden, through the history of modern architecture. The “three desiderata in a slaughter-house”, Cash writes, are “Air – Light – Space”. This is an uncanny echo of the “Light, Air and Openness” sought by modern architects in the following decades. The architectural historian Paul Overy makes that phrase the title of his excellent 2007 history of the impact of hygiene theories on modernism; the phrase comes from Befreites Wohnen (Liberated Living), a polemical text published in 1929, written by … one Sigfried Giedion.

Giedion and the other early modernists were taking their cues (in Overy’s presentation) from sanatoriums, hospitals and spa resorts – but the slaughterhouse is clearly not far away, being governed by the same hygienic concerns. As a space without architecture, a space that is all interior with no exterior, a space of “continuous flow”, the slaughterhouse also has affinities with hypermodern junkspace. An invisible line runs through the slaughterhall, separating the “dirty side” of heads and hooves and blood and guts and other substances from the “clean side” of processed sides of meat. If we think of these halves as “ground side” and “air side”, the abattoir comes to resemble an airport, with death and evisceration replacing check-in and security. Traffic at either end of the process is strictly segregated, and the “individuals” passing through have their identity, origin and destination carefully monitored throughout. There are antechambers where suspect specimens can be isolated and detained. The biggest schematic difference between the facilities is the lack of an “arrivals” hall. There are only departures. This article was first published in Icon’s September 2014 issue: Countryside, under the headline “Meat is modernism”. Buy back issues or subscribe to the magazine for more like this |

Words Will Wiles

Images: Danish Crown slaughterhouse, Horsens, Denmark; Alastair Philip Wiper |

|

|

||