|

Inside the Prada Transformer’s first show, WaistDown |

||

|

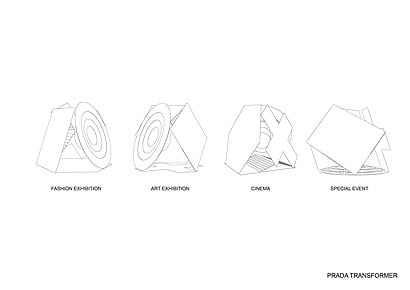

OMA’s latest blockbuster is pretty modest by the standards of the last few years. In fact, it’s a marquee. The perfect retort to the financial crisis? An austerity icon? Not really. More like fashion agit-prop. The Prada Transformer is a machinefor making publicity. The hype had been quite something, videos appearing all over websites explaining how this strange structure in Seoul would work, constructivist renderings of a clunky steel frame looming over models and skirts. This was to be the zenith of the love-in between fashion houses and architecture. The big party itself was a strobe of camera flashes as Korea’s biggest stars swanned around in new season Prada surrounded by gaggles of fans and long tadpole tails of snappers and reporters. Miuccia Prada was there in (or so I was told) a “gladiator” skirt. And the big tent itself was full of skirts: whirling skirts, swirling skirts, swishing skirts, squashed skirts, a resurrection of the fashion house’s Waist Down show which has been all over the world in the past five years. The ceiling was populated by the cut-out catwalk models familiar from the auditorium steps of the New York epicentre, which was, in its just pre-9/11 day, about the only interesting slice of architecture in Manhattan. Taking its cue from Transformer toys and cartoons, this is a building which doesn’t want to be only one thing. Commissioned by Prada as a temporary standalone pavilion in the grounds of Seoul’s 16th-century Gyeonghui Palace, the Transformer can contain an exhibition space, a fashion catwalk, a cinema or an art space. But, unlike its namesakes, none of this can be achieved by a few deft twists. Instead it takes three huge cranes, a couple of hours and a major refit to rotate the PVC-clad steel behemoth so that it rests on a different side, entirely transforming the shape of the interior. This is, without any doubt, the work of an architect who remains intensely uncomfortable with the idea of building, with the permanence and ossification of the final outcome of the construction process. Modernism may have always professed an obsession with the form embodying the function but, ultimately, the look of the architecture was effectively predetermined. Koolhaas is genuinely more interested in the content than the form. This was most clearly seen in his Serpentine Pavilion when the 24-hour marathon Q&A sessions were at the heart of the programme. It is presumably this interest in activity over aesthetics which makes the Transformer such an unsettlingly ugly object. The Gyeonghui Palace, I am informed by my guide, is Seoul’s fifth most important palace. Out of five. Consent would have been too hard at the others. The juxtaposition is extraordinary. The gravelly forecourt is dominated by what looks like the cowl of a monstrous ventilation shaft. The palace sits downtown and is overlooked by the city’s generic, overbearing glass towers. In a city that has smashed its old fabric even more comprehensively than Tokyo, the palace seems a fantasy survival, a fun-park diversion, autonomous within its walls.

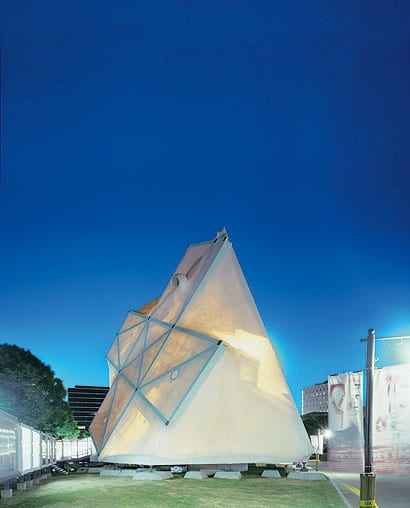

The pavilion sits in the grounds of Seoul’s Gyeonghui Palace, overlooked by downtown’s glass towers In its current incarnation, a truncated cone, the pavilion seems to regurgitate half-digested forms from Isozaki and from Corb’s Firminy Vert. By day it looks like a thing that still awaits unveiling, a little bit Christo. The PVC fabric, which was apparently developed to protect mothballed US aircraft in the aftermath of the Second World War, got a little dirty in the Seoul air, giving it the impression of a stretchy vellum. By night, with the spotlights revolving inside, it’s clubbier, a bit more Ibiza. But the lights do allow the skeletal structure to reveal itself like an X-ray. It is such an odd object that it is difficult to know quite where to begin a conventional critique. It seems spectacularly ill-timed, landing in the midst of a devastating recession. It seems oddly dated in its rather 1960s yearning for adaptability, a temporary architecture not only capable of embracing change but existing for it. And, for a building embodying change, it seems clunky and over-engineered. The most theatrical part of the process, the transformation itself, is not part of the event, but an engineering feat carried out separately to the programme, banished to the service sector. None of which means it isn’t great fun. Prada and its eponymous Foundation have done some extraordinary things, edgy, strange projects which saw a genuine separation between brand and intention. The most recent, Carsten Höller’s eccentrically hip Double Club, half-Congolese restaurant, half-Islington nightspot, has been among the strangest. But there has been a uniquely rigorous separation of art and commerce. Miuccia Prada had been wary of bringing the projects and the products together and it was apparently only at Rem’s behest that she did. The architect’s angle was that fashion is art. Having famously stated that shopping is the last public activity left in our cities, Koolhaas sees little distinction between the cultural activities of the foundation and the fashion and has also suggested merging them with the provision of a Prada archive in his new foundation HQ in Milan.

When the building is rotated, this cruciform facade will become the floor to accommodate Prada’s Beyond Control show Fashion and architecture are, of course, no strangers: a stroll down Aoyama or through Tribeca or SoHo reveals a kind of museum of architecture. Frank Gehry, David Chipperfield, Herzog & de Meuron, Future Systems and Toyo Ito have all done swanky showcase boutiques and the recent exhibition Skin and Bones (seen in New York and London) highlighted the increasingly frenetic interchange of formal and verbal language and practices between fashion and architecture. Fashion loves architecture’s serious intellect, its solidity and permanence; architecture loves fashion’s speed, its freedom and its profile. The Transformer slips somewhere in between the two. It is programmed to change each month. Its next incarnation will be as a movie theatre showing a festival of film curated by Babel director Alejandro González Iñárritu. What is currently the floor will become the screen while seats will be installed on the raked floor, which currently looms above the skirts. After that it becomes an art gallery with a cruciform floor to best display the Prada Foundation’s Beyond Control show and then finally a rather vague notion of a fashion show will appear, the circular floor becoming a catwalk circuit. The basic forms, cross, square, circle, hexagon, fall somewhere between a baby’s shape sorter and Josef Hartwig’s Bauhaus chess set, a cartoonish Platonic modernity. The early photos of the pavilion, showing a lumbering black steel frame, were an enigmatic blend of Tatlin’s Tower and a gyroscope, a supersized sci-fi object with no discernible function. But that weird illegibility is lost when the fabric sheath is slipped over. Covered, it becomes a building, emasculated. There is something of the coarse beauty of the fairground in its structure but, unlike the fairground, when the lights go on, it doesn’t transform into a magical night-time world. If anything, it is weakened. Cedric Price shared some of Koolhaas’s uncertainties about architecture. In virtually the only substantial thing he built, the aviary at Regent’s Park Zoo, you can sense a similar restlessness and dissatisfaction with the finality of the covering. That final layer, in which he used flexible mesh, is the one which concretises the structure, fixes it but which also ends the process. OMA has found a way of continuing that process but, in the process, the building has lost its power. The pavilion also raises questions. Why Seoul? What exactly does it do for the Prada brand? What happens to it afterwards? Seoul remains one of the big growth markets, which settles the first, perhaps the second also. The third, I asked about, but nobody knows. The Transformer also seems to represent a kind of full stop to the explosion in starry pavilions. What Julia Peyton-Jones started at the Serpentine in order to address a chronic lack of event space in the tiny gallery has blown up into a craze for super-pavilions – lavish, hugely expensive structures which may have had their genesis in an idea of the realisation of iconic architecture on an affordable and accessible scale, bypassing planning controls, but which have themselves ended up as overblown monuments. Without the Transformer, Zaha Hadid’s aborted Chanel Mobile Art Pavilion, a shiny doughnut full of handbags which parked in Tokyo, Hong Kong and, most incongruously, Central Park, would have provided the pavilion moment with its epitaph. Now, perhaps, the epitaph belongs to OMA. “At what size,” I asked Koolhaas on my way out, “does a pavilion cease to become a pavilion?” “It’s a good question,” he deadpanned, looking up into the roof to avoid eye contact.

The PVC fabric sheath revels the pavilion’s contents

|

Image Sunkwan Kon

Words Edwin Heathcote |

|

|

||

|

The fashion exhibition space |

||