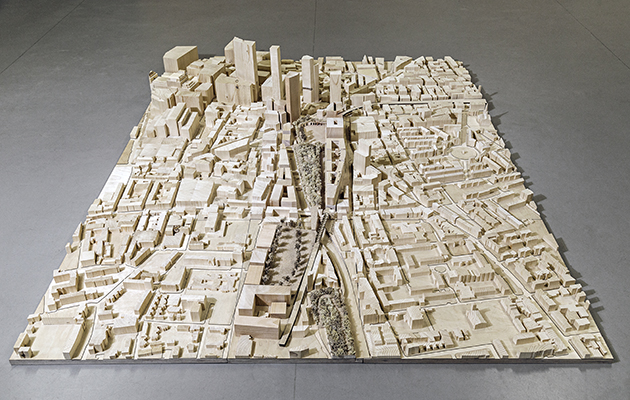

![]() David Chipperfield Simon Kretz at Bishopsgate Goodsyard. Photo: Rolex/Tina Ruisinger

David Chipperfield Simon Kretz at Bishopsgate Goodsyard. Photo: Rolex/Tina Ruisinger

David Chipperfield and Simon Kretz’s ‘thought experiments’ on a delayed £800m London regeneration scheme shine a light on how the UK’s beleagered planning system is failing our cities, writes Jay Merrick

If you’ve been to London, you’ve probably walked past the graffitied Victorian remains of Bishopsgate Goodsyard, and barely glanced at it. Its 4.2 hectare base stretches east from Shoreditch High Street to Brick Lane, with Bethnal Green Road on its northern flank and Quaker Street on the south side. It was built in 1840, and in the 1930s marshalled more than 50 freight trains a day, laden with thousands of tonnes of fish, fruit and vegetables.

But since the 1970s, and despite the Overground station and BoxPark on its northern edge, the Goodsyard has been a defunct urban mortuary slab where two major regeneration proposals have failed. It has also been the recent focus of ‘thought experiments’ by 36 Swiss urban design students, and their radically different approach to its potential redevelopment ignites a fresh debate about Britain’s private-sector-led urban regeneration system.

When British developers target land development parcels, there’s a ritual dance with local authority planning departments: the creation of a design brief, public consultation, design development, objections and compromises. In most cases, the developers get to build more or less what they asked for in the first place.

The Goodsyard stretches east from the City edgelands to Brick Lane

The Goodsyard stretches east from the City edgelands to Brick Lane

These players, and the increasingly marginalised architects sandwiched between them, operate in a planning system corrupted by continuing cuts in staff and expertise. This process began in the 1970s when the Conservative government (and subsequent Labour governments) decimated professional planning staff and waved through flaccid, market-led planning regulations.

In 1976, according to Finn Williams of planning support agency Public Practice, 43 per cent of architects working in London were employed by various kinds of local authority. Today, there are 25,000 architects in London, but fewer than 200 work in the public sector. Which means that most councils have no in-depth ability to judge or fend off regeneration proposals whose architecture, or so-called placemaking, is essentially an exercise in real estate profitability.

The nine Goodsyard ‘thought experiments’ produced by students from ETHZurich give pause for thought. The project was proposed and propelled by one of the world’s most eminent architects, Sir David Chipperfield, and Simon Kretz, a 36-year-old practising architect and ETH academic. They were brought together by the Rolex Mentor and Protégé Arts Initiative, which has been pairing major figures in arts and design with talented tyros since 2002. The architectural mentors who preceded Chipperfield were Peter Zumthor, Kazuyo Sejima and Alvaro Siza. Chipperfield is the first of them to create a shared project that examines city development as a theoretical exercise: ‘Simon and I just kept meeting and having discussions about turning [urban design ideas] from a series of anecdotal opinions into something more structured and with substance, to show that you could inject other criteria for investors.’

![]() The ‘thought experiments’ involved nine teams of Kretz’s ETH students. Photo: Rolex/Tina Ruisinger

The ‘thought experiments’ involved nine teams of Kretz’s ETH students. Photo: Rolex/Tina Ruisinger

Chipperfield’s first projects were in Japan and Europe, which meant that he had, first, to understand the unfamiliar cities and cultures he worked in; since then, he’s always contended that urban design has to consider more than the red line of site boundaries. In Switzerland, and some other European countries, the design of urban regeneration projects is examined by planners as synergistic parts of much wider town or city contexts than is the case in Britain, where developers copy-and-paste near identical developments wherever they can.

The ETH students were split into nine teams to study the Goodsyard site and outlying areas, and the nine speculative projects they produced, under the leadership of Chipperfield and Kretz, tested designs whose social, cultural and commercial effects would extend well beyond the mouldering crust of the Goodsyard.

The site has been the scene of an 11-year campaign by the joint developers Hammerson and Ballymore to push through an £800 million mixed-use tableau of high-rent towers, chunky blocks, elevated park, maximised retail opportunities, and minimal social housing.

![]() Plan of the 4.2ha Goodsyard site, which has been disused since the 1920s. Photo: Rolex/Tina Ruisinger

Plan of the 4.2ha Goodsyard site, which has been disused since the 1920s. Photo: Rolex/Tina Ruisinger

The developers’ first scheme featured unusually high towers which loomed like tectonic bovver-boys over Shoreditch. Christopher Costelloe, director of the Victorian Society, said the scheme would be very suitable for a suburb of Shenzhen; and Jules Pipe, the then Mayor of Hackney, said the towers were ‘on a vast scale and would damage the whole local environment. The housing provided would be luxury accommodation, to be bought mostly by overseas investors.’ A revised scheme reduced the height of the towers, but its prime real estate vibe remained and it was shelved after strong criticism from the Greater London Authority.

How can it take 11 years to produce unacceptable schemes like these? Is it because local authority planning strategies are too dependent on advice from the developers’ Greek choruses of consultants, who make reassuringly informed comments about issues such as contextual sensitivity and the urban realm? In our bigger cities, this modus operandi can produce impressive urban tableaux such as Broadgate, or Birmingham’s Mailbox. But it more commonly leaves a spoor of generic landmark-iconic-unique-stunning archidental implants that have none of the holistically city-sensitive qualities of projects such as the Lyon Confluence in France, Antwerp’s Strategic Structural Plan, or Zurich’s ongoing Zentrum Affoltern development.

‘When you have someone selling a 60-storey tower and saying Jane Jacobs is their hero, then nobody believes in anything,’ says Chipperfield. ‘We need a clear, rich dialogue between planners and architects, not a confrontational one. Why can’t we say that cumulative [urban] things are part of the city? We don’t have the language to have these conversations, and once you’re on a one-by-one project basis, you can’t solve these problems.’

![]() David Chipperfield Simon Kretz spent two years collaborating on the project. Photo: Rolex/Tina Ruisinger

David Chipperfield Simon Kretz spent two years collaborating on the project. Photo: Rolex/Tina Ruisinger

The Goodsyard projects expose fundamental questions embedded in Swiss planning methods. How do you ensure that urban regeneration projects contribute to an area’s quality of urbanity? How can individual developments have coherent relationships with the evolving city as a whole? Do they support a broad demographic mix? And does the developer’s or planner’s vision come anywhere near addressing those questions?

‘Urbanity is quite a complicated term,’ admits Kretz. ‘It includes many different perspectives – historical, aesthetic, and the way societies organise their lives in a city-like form. You’re also talking about the social and psychic dimensions of the city, and the imagination of the city. These projects all had one common belief: that one can only act if one understands the local urbanity.

‘When I listen to planners in London there’s a fast discussion about liberalism and the way things are in private hands, which seems very defensive. The planners fight hard but it’s very difficult to push basic things through. This reflects the position they are in, a reactive position – damage control to a certain degree. They say things like ‘at least we got this bridge’ or ‘at least we got 10 per cent social housing’. But we are interested in the imagination of the sites, the role of sites in a larger context. I don’t see this in London.’

The students’ test projects had very different individual aims, such as the exploration of ownership patterns; connections beyond the Goodsyard into the East End; or the possibility of a megastructure covering the whole site.

![]() Much of Kretz’s work explores how architecture relates to the wider city. Photo: Rolex/Tina Ruisinger

Much of Kretz’s work explores how architecture relates to the wider city. Photo: Rolex/Tina Ruisinger

Not all of the speculations are feasible, but they do open up a wider and more speculative range of regeneration scenarios than is normally possible in British laissez-faire design and planning processes, which are locked into commercial business models. ‘How can people ignore future urban reality without really discussing it?’ asks Kretz. ‘If you don’t do that, you are only a consumer of urban space.’ Chipperfield hopes that the research, recently published in a book that will be presented at the Rolex- sponsored Venice Architecture Biennale in May, ‘is not a lone cry in the dark. Do we front up to the notion that there have to be structures and agencies in place? Isn’t there a policy of resources and intelligence that should be engaged? The lack of linking [urban developments] together is completely contrary to how things work in the world.’

He suspects this is one reason why many younger architects are thinking more tactically about how they contribute to cities. ‘In Switzerland,’ he adds,‘planning is a valued profession. There should be huge buildings full of planners in London, too. Good planning could actually do much more than architects.’ About 150m due west of the Goodsyard lie the remains of the 16th-century foundations of the Curtain Theatre, where Romeo and Juliet and Henry V were first performed. The hallowed footings will soon become a heritage feature in the podium of a glitzy apartment tower with a hideously presumptuous name: The Stage (‘Presenting Shakespearian heritage, Shoreditch creativity and City glamour,’ according to the developer’s scriptwriters).

Variations on this ruthlessly cliched hokum characterise the planning and design of our urban regeneration projects, in which the idea of the city as a holistic organism appears to have been lost in a shuffle foreseen by Philip Larkin’s 1972 poem, Going Going:

For the first time I feel somehow

That it isn’t going to last,

That before I snuff it, the whole

Boiling will be bricked in

Except for the tourist parts …

On Planning – A Thought Experiment, edited by Simon Kretz and David Chipperfield, is published by ETHZurich and Walther König