|

|

||

|

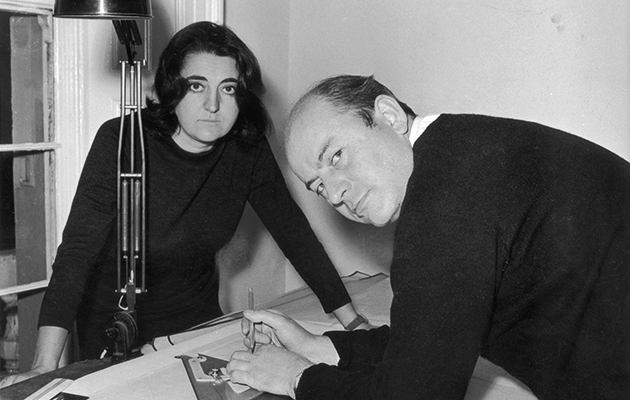

As the demolition of Robin Hood Gardens begins, Peter Smisek explains why he continues to find its architects so compelling The choice of one’s favourite architects, rather like one’s favourite band or beverage, is rarely conscious or rational, being more dependent on a set of largely random circumstances. My own lasting love affair with the Smithsons started eight years ago, when I borrowed their definitive monograph Charged Void: Architecture. The rest is (personal) history. The myth surrounding Alison and Peter Smithson is, of course, largely of their own making. Though they were catapulted to fame by their Hunstanton Secondary Modern School (1949–54), the Smithsons built their reputation on the back of relentless (self) publication. They wrote about everything: their heroic modernist predecessors and contemporaries; the welfare state and consumer society; a future in which everything would be plastic; their miniscule summer retreat; their Citroën DS; and their interest in the everyday, which drew on a wide range of references, beginning with Beatrix Potter and ending with their self-made Christmas cards. Their writing and buildings provided an early and rich theoretical framework for brutalism. Yet the Smithsons’ built projects employed glass, brick, steel, Portland stone, aluminium and wood. Only Robin Hood Gardens – now being demolished – owes its appearance chiefly to concrete. They were also the ultimate tragic revisionists. They dismantled the dogmatic CIAM (Congrès internationaux d’architecture moderne) together with their Team 10 contemporaries, yet never came up with a viable alternative. In their 1959 London Roads Study, they proposed motorways that would rip apart the centre of the capital, but by the 1960s and 70s were arguing for retaining and enhancing the walkability of Bath and Cambridge. Their proposals for streets-in-the-air and urban megastructures made way for a gentler ‘conglomerate ordering’ that emphasised gradual growth and clustering within found urban and architectural tissue. Sadly these more nuanced, latter-day positions were drowned out in a postmodern world unreceptive to well-intentioned architecture. But the couple’s greatest achievement was not their limited building output, nor their extensive writing portfolio, but their ability to convince others, myself included, that architectural theory, building praxis and everyday life should be all one and the same. This is an edited version of an article that first appeared in Icon 160 |

Words Peter Smisek |

|