|

|

||

|

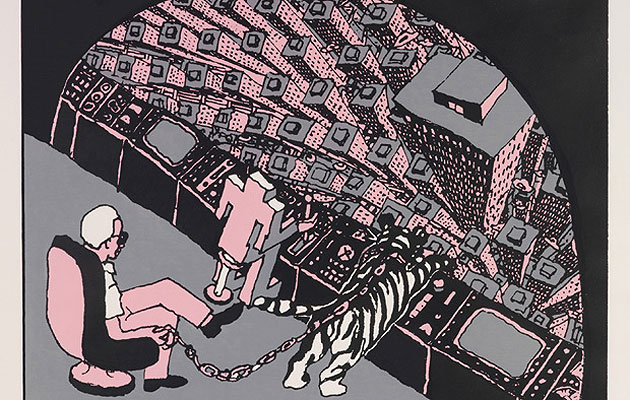

Welcome to a nightmare of identical high-rise towers, car-jammed highways and swarming supermarkets; a city gobbled up by a corporation which stamps its signature on everything from newspapers to nuclear weapons; a metropolis whose citizen-slaves are so uniform they may have been bred in incubators, and who all rise at 7am, pop happiness pills and open the front door to leave for work in unison. Soft City was the future according to Norwegian artist Hariton Pushwagner back in 1969, when he started sketching the graphic novel of the same name. The invasion of concrete, steel and glass, the increase in mass housing, as well as the clashes between utopian and dystopian thinking, all fuelled the artist’s vision of the dark, unpalatable flip-side to Le Corbusier’s machine for living. More than 40 years on, his day in the life of a soft citizen in conveyer-belt-ville – half satire, half speculation, one senses – is just as potent. Gloomy times call for gloomy visions and presently dystopias and the apocalypse are everywhere – trouncing vampires in young adult fiction sales (thanks to The Hunger Games and Blood Red Road) and looming large in many a recent arthouse film (Tarr’s The Turin Horse, von Trier’s Melancholia). The dead end of the capitalist dream may feel like over-mined territory but taking a tour of Soft City at Milton Keynes’ MK Gallery in the long-overdue first UK retrospective of Pushwagner’s career – its 154 pages taking over the central exhibition space – it is clear that the novel’s scope and style set it apart. Largely monochrome, with its minimalist pencil markings and smudges of Tippex, it is the anthesis of the colourful, exaggerated mega-dystopias of most graphic novels. Burroughs, Brueghel and Warhol are really the nearest points of reference. Repetition and conformity were the twin obsessions of many consumer-curious pop artists in the 1960s, and are undoubtedly shared by Pushwagner. Windscreens and rear-view mirrors are filled with a parade of indistinguishable hatted and suited silhouettes sat in office-bound cars. Meanwhile, tower-block homes are constructed simply with rows of roughly drawn squares disappearing off page, producing an epic, dizzying spectacle as Pushwagner moulds his city’s architecture to squeeze out any glimpse of the horizon. Peering through the windows in other scenes reveals the lives of the inhabitants within these duplicate interiors (complete with 1960s swivel armchairs) paused at precisely the same TV dinner moment. Intricacy though also plays its part, particularly when it comes to eyes. Bingo, the toddler who has yet to turn automaton and who acts as our guide onto this world, has black pupils dilated in awe while the fine lines of his irises are drawn in such detail so as to appear stretched with fear. Compare this with the faint facial features and vacant expressions of his parents, totally in tune with their bland conversations (full of “dears” and everyday nothings). Pushwagner is clearly fascinated with language – from the slogan-speak of the city’s controller (“classic … just like cash”) to the cut-up style of the newspaper headlines mangled with adverts (“dead men kill sweep mind clean the easy way”). Then there’s that word “soft” (influenced, one suspects, by Burroughs’ novel The Soft Machine), full of the post-war consumerist promise, ushering visions of a comfy life but also malleable, docile citizens. Elsewhere in the gallery, more recent work can be found – canvases depicting hallucinatory, wobbly cityscapes as well as space-opera style re-imaginings of Soft City (with colour, flying saucers and babies on leashes). But these crazy, exuberant visions of hell don’t quite pack the same chill as his magnum opus. Only Pushwagner’s spectacular Apocalypse Frieze – seven intricate Hieronymus Bosch-esque paintings depicting such horrors as human hatcheries and state-controlled genocide – rivals Soft City. What would Hard City look like, we might wonder? A totalitarian state much like the one in Orwell’s 1984 perhaps. Soft City though resembles Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World – it is what awaits us when desire and warped utopian thought take over. And could there be a more apt backdrop for this exhibition than the utopian experiment that is Milton Keynes? Outside, amid the wide car-dominated boulevards and bland mid-rise blocks, Soft City doesn’t seem so far away. Good night. Soft dreams. |

Image Hariton Pushwagner

Words Isabel Stevens |

|

|

||