|

|

||

|

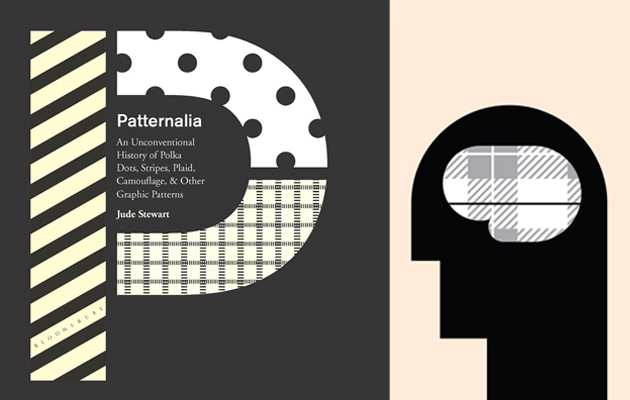

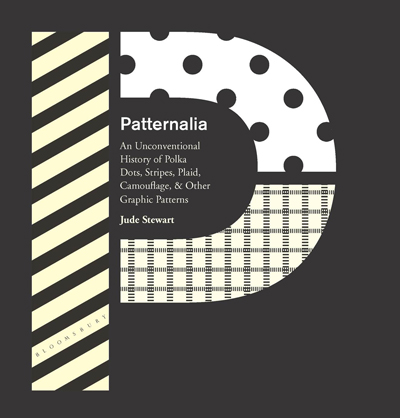

From William Morris’s floral wallpaper to the polka dot bikini, this book explores the historical, cultural and political associations of the patterns that pervade our everyday lives, says Anja Wohlstrom Patterns are everywhere, from the wood-grain in your flooring to the stripes of your blinds, to your clothing and even your food, says Jude Stewart in her new book.

In Patternalia, she explores the historical and cultural associations of the patterns we encounter every day. They are often dismissed as mere decoration or worse, as modernist architect Adolf Loos believed, dangerously indulgent. But Stewart argues that patterns “connect the cool, abstract world of science to the feverishly meaning-mad world of people”, pointing to the personality we attribute to them – demure polka dots, wholesome gingham, decisive stripes. Patternalia provides a cultural history of pattern, shedding light on what they mean across cultures, disciplines, time periods and contexts. It is fast-paced and covers a lot of ground, while a handy cross-reference system allows you to flick back and forth as you explore.

“No pattern should be without some sort of meaning,” said William Morris, the king of wallpapers, in 1881. Morris’s designs were the height of interior style at the time, with densely flowered designs with names such as Strawberry Thief (“birds eyeing strawberries amid detailed blossoms and veins”) and Trellis (“red poppies snaking through trelliswork, studded by bluebirds”). The chapter on curves and florals starts with Morris’s story, and finishes with wartime camouflage – a pattern with the contradictory purpose of both hiding someone and marking them out as part of a group.

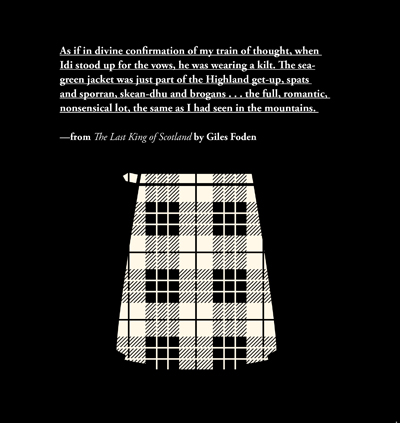

My favourite “colour” is stripes, so I was excited to learn more from the lines and stripes section, which starts with a quote from Paul Klee: “A line is a dot that went for a walk.” The section takes in prison uniforms (whose stripes echo the thick, vertical bars of prison cells), the ties of public-school boys and business men (“once striped, always striped”) and the folk tales that explain how zebras and tigers got their markings. Barcodes are segmented into 95 vertical stripes, we learn, and stripes of barber’s poles date back to the time when barbers practiced phlebotomy – patients undergoing operations had to grasp a pole to make the blood flow more freely, and this became stained with blood.

In the dots and spots section we learn about the polka dot bikini, immortalised in Brian Hyland’s 1960s song, the practice of reading moles and “dot activism”, as practiced by artist Yayoi Kusuma in her critique of capitalism. According to Stewart, every pattern – from plaid to gingham – has a history. The book is packed and buzzing with intriguing stories and cultural references. A fun and informative read.

|

Words Anja Wohlstrom

Illustrations Oliver Munday |

|

|

||