|

|

||

|

William Gibson is famous for two things. First, he “predicted the internet”, at the precociously early date of 1981. His subsequent novels, starting with Neuromancer in 1984, did much to equip our imagination for the coming connected world. Second, he coined a handy phrase which serves well as a basis for further prophecy: “The future’s already here: It’s just not evenly distributed.” You can tell what tomorrow’s world is going to be like by looking at the right parts of today’s world. The seemingly effortless futurity and trademark dry, cool style comes across on every page. A Rolling Stone article written in 1989 freely uses the term “the Net” (capital N) to refer to interlaced communication and media technologies and their all-encompassing disruptive effects. Nineteen Eighty-Nine! But he’s already using the term in the present tense. “I think it’s safe to say that I was pretending to know what ‘the Net’ might be, when I wrote this,” Gibson says. As if that matters. In “Rocket Radio”, Gibson recounts that his first encounter with audio cassettes was finding a brown tangle by the side of the road. What’s new technology to the rest of the world is already, at the moment of discovery, landfill to Gibson. He’s always one step ahead. How does he see the future now? We’re too late! The monolithic “capital-F” concept of the future is already over, says Gibson, shaken apart by acceleration. Ahead is merely “more stuff … the mixed bag of the quotidian”. Often it’s places that give Gibson his glimpses of the coming world. Distrust includes “Disneyland with the Death Penalty”, his 1993 essay on Singapore, an absolutely brilliant bit of fly-by travel writing that became the much-copied model for other, less talented journalists writing about emerging stars of the non-West, particularly Dubai. Re-reading “Disneyland”, you get a sense of how on the ball Gibson was about a lot of things – the fact that neoliberal capitalism didn’t need liberal democracy to thrive, for instance, and the theme-park unreality of the places it was creating. Japan, in some senses Gibson’s spiritual second home, is the book’s most frequent destination. Why? “Japan is the global imagination’s default setting for the future.” Over several essays Japan’s situation “several measurable clicks down the timeline” is lovingly and brilliantly analysed. New York and London are also studied, with a sympathy that is impressive from a non-native. And object culture is given rapturous autopsies in essays on eBay, watch collecting and Tokyo department store Tokyu Hands. From cover to cover, Distrust is sheer pleasure; invigorating pleasure, never sedative. The contextual notes added by Gibson to each entry work marvellously, tying in what would otherwise be a somewhat disparate collection into a unified, autobiographical whole. It’s also good of the publisher to put the original location and date of each essay at its head, rather than burying this information elsewhere, in the habit of nearly all other prose collections. The only flaw of Distrust is that, for a compilation spanning three decades, it’s on the slim side – 260 pages at a generous type size, and with title pages for each essay. But being left wanting more is no bad thing. Distrust That Particular Flavor by William Gibson, Penguin Viking, £12.99.

|

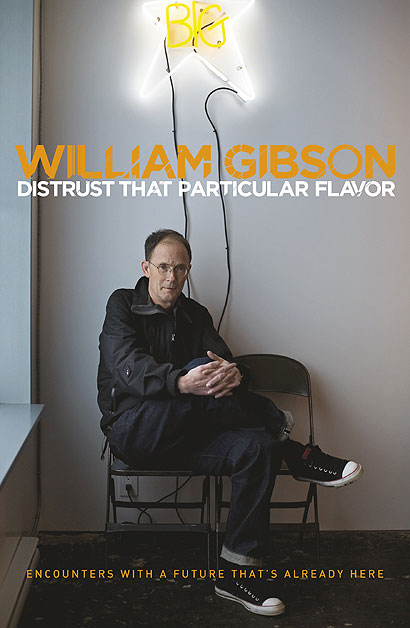

Image Penguin Viking

Words Will Wiles |

|

|

||