Designer and artist Grace Wales Bonner shows Priya Khanchandani around her new Serpentine Gallery exhibition

Grace Wales Bonner eschews attention. Yet for someone who is not an active social media user, nor one to bask in the media spotlight, she has developed an impressive reputation since she set up her fashion business, armed with a BA from Central Saint Martins, in 2014.

We meet at her exhibition at the Serpentine Gallery. Titled A Time for New Dreams, it unravels Bonner’s design process through displaying the work of artists and thinkers who have influenced her, or form part of her own cultural lineage, such as Ben Okri and Ishmael Reed.

‘The starting point for me with this exhibition was thinking about the role that writers play in tracing connections between Africa and the Caribbean,’ Bonner, aged 28, explains, ‘in the sense of interpreting ideas of ritual and spirituality, and how those things are transferred and integrated in the black Atlantic.’

As she leads us on a tour of the exhibition, it is clear that Bonner does not pander to her audience and is unafraid to use academic concepts and references. Initially shy and softly spoken, but clearly self-aware, she grows more confident when we subsequently talk more privately about her engagement with cultural ideas. She tells me her interest in theory began during her time at Central Saint Martins, although she was always interested in identity and representation.

‘I remember reading Homi Bhabha’s The Location of Culture,’ she says, ‘and thinking about this idea of a third space between space.’ The work of postcolonial theorists such as Bhabha, who in the 1990s created a new language for talking about hybrid identities, has deeply shaped the way Bonner thinks. Bhabha wrote that where cultures come together, in places like London where Bonner – whose father is Jamaican and mother is British – was born, what results is not simply a mixing or dilution of cultures but something hybrid and new.

‘It kind of gives you a bit of freedom; like I feel I have a bit of licence to play, to play with history,’ she says. ‘And that’s something I’ve been talking to writers about. I feel free because of those intellectuals and that kind of theory.’

Bonner is motivated by design as a vehicle for expressing cultural identity, both her own and that of others. For her first collection, she worked with cowrie shells and mixed them with Swarovski crystals in order to juxtapose currency in African shells, which have been used for trade, and European ideas of luxury.

‘There are also different types of embroidery that I have been interested in, that come from different cultures, like South-east African beading or South Asian beading techniques,’ she says of craft practices that intersect with her work. ‘So I think it’s quite cross-cultural, the way that I interpret different traditions.’

Bonner’s awareness of how blackness is represented in British culture – and certainly in the fashion industry – has been instrumental to her work and how it is shown (such as through the use of black models in her shows). ‘The things I know about black culture and identity, I wasn’t seeing reflected anywhere. I was seeing blackness used in fashion to communicate a very “street” aesthetic,’ she explains.

Is she trying to subvert that? ‘I think I’ve always just tried to show a very gentle and beautiful representation of black masculinity,’ she reflects. ‘My vision of masculinity and black masculinity was very much about this idea of a very sophisticated black male who is also sensuous and gentle in the way that he communicates and looks.’

The Serpentine exhibition is a homage to intellectual black culture. It is framed around the notion of the shrine, which is the subject of American historian Robert Farris Thompson’s book Face of Gods: Art and Altars of the Black Atlantic World. Bonner sees Thompson’s writing as a link between Caribbean spiritual practice and how it manifests across the Atlantic. This led her to reflect on how to visualise spirituality.

‘I definitely consider myself spiritual, and I think that this show is very much a reflection of that,’ she says, ‘what’s happening in my mind, and where I am, and how I connect to time, and how I connect to ancestors.’ The shrines displayed in the exhibition manifest spirituality in a number of varied forms.

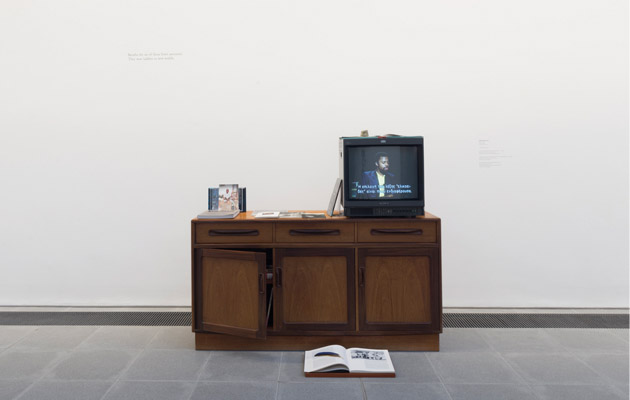

Her own ‘shrine’ comprises a found cabinet displaying cultural artefacts of meaning to her, such as a copy of The Black Monastic by Theaster Gates, a Ben Okri poetry collection, a book on magical realism and a 1988 edition of Wire magazine featuring a black figure on the cover and lead story about jazz. Such objects are a clear tribute to the discourse on black culture that precedes Bonner, and of which she seeks reciprocally to become a part. It is clear how she connects to those works from a couplet by Okri pasted on a wall, which reads: ‘Breathe the air of those brave ancestors; / They were ladders to new worlds.’

Other installations by invited artists like Kapwani Kiwanga, Paul Mpagi Sepuya and Eric N Mack use a variety of media to create physical manifestations of devotion. The content is not restricted to black culture, though. One is a meditation area displaying Hindu deities, where she has invited musician and meditation practitioner Laraaji to perform a series of meditation sessions. This exhibit results from Bonner’s interest in India – she has travelled to Udaipur, Goa, Delhi and Madras and it is a place she feels ‘spiritually connected to’, particularly because of the interaction between the migrations but also ‘through the idea of reflections, like Bollywood and Nollywood’.

Bonner has become central to the men’s catwalk during London Fashion Week. In 2015, she was awarded the Emerging Menswear Designer Prize at the British Fashion Awards. And within weeks of showing her first collection during London Fashion Week in 2016, she was awarded the LVMH Prize for Young Fashion Designers, worth €300,000 and considered a foothold into the major fashion houses.

But it is no surprise, given her interests, that Bonner’s aspirations go well beyond the conventional fashion circuit. In her own words, her ultimate ambition is not to become a global fashion giant, but rather ‘to be able to show my thought process, my work and my collections in context, because they can’t be isolated from that. They can’t just exist in this fashion bubble.’ This thoughtful, curatorial approach has come to define her as a designer and has distinguished her quickly as one of the most innovative fashion designers of her generation.

Although embraced by the fashion industry, Bonner is reluctant to pander to its tendency towards throwaway, seasonal products. And rather than dress celebrities who are famous for celebrity’s sake, her dream is to dress the important black intellectuals and artists of our time. Her biggest personal achievements to date have been dressing Ben Okri and Arthur Jafa, which is telling for someone who just out of fashion school was awarded fashion’s most prestigious accolades.

More recently, Bonner’s work has trickled beyond the purview of fashion opinion-formers such as Vogue. It has begun to be embraced by the design community for the consciousness of its representation and materiality, leading to Bonner winning the Emerging Talent Medal at last year’s London Design Festival.

Bonner’s Serpentine show will culminate in the launch of her Autumn/Winter 2019 collection, Mumbo Jumbo. The collection is set to feature the clothing of archetypal characters of her choosing, such as the artist-shaman, a West African spiritual healer and a gathering of Howard University intellectuals.

It remains to be seen if, following an exceptional start to her career, Bonner can live up to potentially unrealisable expectations for someone of her age, including the assertion by Serpentine artistic director Hans Ulrich Obrist that she is a ‘visionary’ who ‘it was always a dream for us to work with’. But her willingness to articulate difficult notions of intercultural relations and challenge gender conventions is certainly a breath of fresh air. Given the integrity imbibed in her work and the honest intellectualism of her approach, her success certainly deserves to be sustained.

This article originally appeared in the April 2019 issue of Icon