|

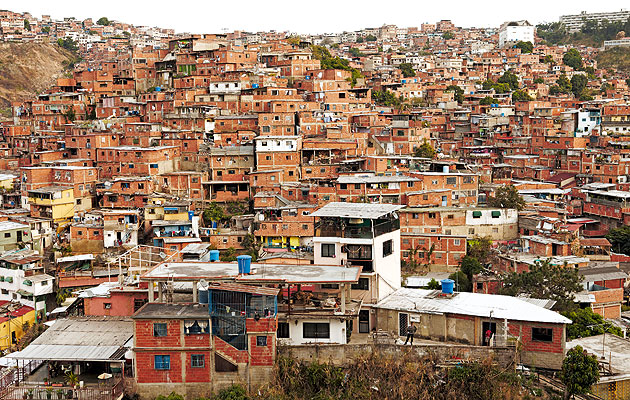

The ghetto of San Agustin spreads across a mountainside in the centre of Caracas – a typical slum, or barrio as they say in Venezuela. In this labyrinth of huts without a sewage system or running water stands the Monocable Gondola Detachable, a 1,721m-long cable-car with 50 eight-person cabins, which opened in January this year. The barrio itself isn’t a story, the cable-car even less so. The combination of slum and cable-car already exists, in Medellín, Colombia. This project is all about its social dimension: it does what Medellín’s cable-car doesn’t – connect the barrio and its people directly to the transport system of the city. Its full name is Teleferico para Transporte Masivo Interurbano (cable-car for inner urban mass transportation), and Hubert Klumpner and Alfredo Brillembourg of local practice Urban Think Tank (UTT) would like to see the concept become “an international standard”. Their office is in El Rosal, a business quarter of Caracas. Klumpner, born in Salzburg, studied architecture with a focus on city planning in New York at Columbia University, where he met Brillembourg, a Venezuelan of Dutch descent. After graduating, Klumpner joined Brillembourg as partner at UTT and they focused on building orphanages, schools for autistic children and sports facilities. In 2002, UTT organised a project with the German Kulturstiftung des Bundes (culture foundation) to develop strategies to upgrade slums and research the “informal city”. San Agustín became the focal point. “The topic is a classic,” says Brillembourg. “Ever since cities have existed there has always been a dichotomy of the formal and informal.” On the one hand are the planned, strategically built areas and on the other, the uncontrollable, spontaneously developing spaces. In between, a rift. “The challenge,” he says, “is to eliminate the boundaries between these spaces … so that the slums don’t deteriorate further, but rather become a resource for the city.” This is especially acute for barrios such as San Agustín that are confined by a river, a motorway, dense vegetation and steep mountainous slopes. “Apart from a pedestrian bridge crossing the motorway, there wasn’t really any other entry point to the barrio before the cable-car was built,” says Brillembourg. The barrio was never integrated into the infrastructure of the city, as building a road would have meant demolishing one third of the housing. “Everyone saw a mountain full of huts,” says Klumpner. “We saw a house as high as a mountain. So we asked, ‘Where is the lift for this house?'” In 2003, UTT presented a concept for a cable-car, but it fell on deaf ears. It wasn’t until 2006, after Venezuela’s president Hugo Chávez attended an EU summit in Vienna and returned fascinated by the cable-car systems there, that Metro de Caracas commissioned the Brazilian firm Odebrecht and Austrian cable-car expert Doppelmayr to build a system for San Agustín. But as Doppelmayr lacked the experience of working in slums and Odebrecht had never built a cable-car before, the head of engineering at the Metro, Cesar Nunez, turned to UTT – “those crazy architects who wanted to build a cable-car” – for help.

The Monocable Gondola Detachable connects the barrio of San Agustín with the rest of Caracas To enter the barrio of San Agustín, which is notoriously dangerous, we need escorts. Luis and Charli both live in nearby Santa Rosalia and worked as UTT mediators while the cable-car was being built. Luis is an elected representative in San Agustín who is responsible for “health, cleanliness and culture”. What does that mean? “A lot of paper work,” he says, “and I also have certain jobs in the informal sector.” But he never quite explains that either. He has a pass that says “commission for citizen security”. Charli has neither a pass nor, apparently, a surname, but what he does have is a car. And so we begin our journey to the cable-car’s summit station, La Ceiba. Ever since president Juan Vicente Gómez invited American firms to fund Venezuelan oil in the 1920s, urban planning in Caracas has been dominated by the car. American industrialist John D Rockefeller invited architects and planners such as Wallace Harrison and Robert Moses to develop the Proyecto de Futuro. The result is concrete highways weaving through the equally harsh concrete block architecture. Suddenly Charli turns off the highway onto small, winding streets past debris and rubble until the car stops in front of a row of brand-new apartment blocks. Next to it towers the cable-car station La Ceiba. It looks like a spacecraft on a pile of gravel against the backdrop of a slum. Luis whistles through his fingers and calls for Marlin Hernandez, the woman involved in distributing the new flats among the 273 families that had to be relocated to build the cable-car. Women stick their heads out of windows, children stop and stare. Soon she appears – a small, round woman with short legs and a chipped front tooth. She leads us further into the barrio. She knows the invisible borders, the current balance of power on the street. She introduces us everywhere, over-gesticulating and speaking very loudly. It seems as if she is throwing stones in the water for the message to spread like waves across the barrio. We climb through a fence, past a dilapidated rusty red brick hut. Some huts only have curtains as doors, others bars rather than glass windows. A teenager with a hazy gaze is hunched on a step. Luis knows him. “This is one of our bad boys,” he says. The boy mumbles something and sneers. Klumpner talks about how they took photographs of teenagers in 2002 as part of the slum upgrade project. “Many of them are dead now.”

Urban Think Tank’s Hubert Klumpner and Alfredo Brillembourg San Agustín is typical in South America, not just in Caracas and big cities like Quito, Bogota or La Paz. All over Latin America housing for the poverty-stricken has developed in almost inaccessible terrain. The isolation increases the problems. Klumpner and Brillembourg have been researching the topic for years. “Nine out of 15 children live in slums,” says Klumpner. “We can’t just get rid of the slums, we must make these zones of poverty into zones of growth, or else the situation will escalate.” At UTT, they view the cable-car in a similar fashion. “A cable-car alone can’t be a solution, but it can be the basis for a solution.” Previously people who wanted to reach the Parque Central metro station had to descend 600 steps, which took around 45 minutes. In the cable-car it takes five. People don’t lose valuable time getting to work and don’t have to fear getting back after dark. Injured people can get to the hospital faster, the police can reach the district much quicker and older people are more mobile. UTT plans to create hubs around the cable-car stations including supermarkets, pharmacies and radio stations, and Klumpner hopes that “the concept will evolve”. In Medellín, the cable-car has already had an effect. The people there call it “poetry in the sky”. Brillembourg says that crime has been reduced in the barrios. Psychology plays a vital role. The cable-car is a statement: it says the politicians are doing something for the barrio and that its people aren’t second rate, which consequently reduces bitterness and aggression. Many Chávez critics have questioned where the millions made from Venezuelan oil have gone. They see this project as symbolic: Caracas has many barrios, yet this cable-car happens to be located on the way into town from the airport, and makes use of flashy materials such as granite and marble. In total the project cost $270 million, around $157,000 per metre. Nunez, the Metro’s head of engineering, is supposed to start on a second cable-car in the Filas de Mariche barrio. “We certainly can’t afford this finish again,” he says. Finally we get on the cable-car and spend the rest of the day travelling back and forth, viewing the barrio from above. As we return to La Ceiba station, a young cable-car assistant approaches us. There has been a shooting at the station in San Agustín. The bad news: the police are letting people get off but nobody on. The good news: on the other side of the platform the next cable cabin to Parque Central is approaching. Only five minutes, one last look at the barrio and then straight into the metro and home.

The Monocable Gondola Detachable connects the barrio of San Agustín with the rest of Caracas

The Monocable Gondola Detachable connects the barrio of San Agustín with the rest of Caracas

The cable-car’s summit station, La Ceiba

The cable-car is a boost to the barrio’s self-esteem; a second is proposed |

Image Michael Hudler

Words Gerhard Waldherr

Translated and edited by Kerstin Zumstein |

|

|

||

|

UTT viewed the mountainside barrio as a single house, and built that house a lift |

||