‘I believe, we are more and more aware that if we don’t try to deal with inequalities, we will never seriously slow down global warming and climate change’ says Stefano Boeri, on Triennale Milano’s 24th International Exhibition theme. As the Triennale gears up for the launch on 17 May 2025, ICON chats with Stefano Boeri, President of Triennale Milano, to find out more

Photography courtesy of Unsplash

Photography courtesy of Unsplash

Words by Joe Lloyd

Stefano Boeri is thinking about cities and ecology. The Milan-based architect, planner and educator has been the President of the Triennale Milano since 2018. Next May he will convene the 24th edition of the exploratory design exhibition. The theme will be Inequalities. How to Mend the Fractures of Humanity, a bold, broad subject for an exhibition. It will seek to show how design can help to mend the fractures in and across human societies before it is too late. A year ahead of the exhibition’s opening, I spoke to Boeri about his choice of topic.

‘The main reason is related to two issues,’ Boeri explains, ‘One is that we basically want to talk about cities.’ Urban areas bring the beneficiaries and victims of inequality cheek-by-jowl. One potential subtitle for the exhibition is The City of the Rich and the City of the Poor ‘so to try and redefine,’ Boeri continues, ‘a possible equilibrium between these two spheres. I think it’s important to observe from different perspectives how inequalities have been accelerated in the last 10, 15 years.’ The second issue relates to ecological transition. ‘I believe,’ Boeri says, ‘we are more and more aware that if we don’t try to deal with inequalities, we will never seriously slow down global warming and climate change.’

It is an intricate web of issues for an exhibition to cover. But the Triennale Milano has form when it comes to using design to explore weighty matters. It has its origins in 1923 but achieved its present location and schedule years later, when it also became a member of the Bureau of International Exhibitions. It is still held within architect Giovanni Muzio’s Palazzo dell’Arte in the Parco Sempione in central Milan. Its impact on the modern conception of architecture and design cannot be underestimated. The 1947 iteration even created an entire new neighbourhood of Milan.

Photography by Delfino Sisto Legnani-DSL Studio, courtesy of Triennale Milano, featuring Stefano Boeri

Photography by Delfino Sisto Legnani-DSL Studio, courtesy of Triennale Milano, featuring Stefano Boeri

It has long faced the future. ‘After the Second World War,’ says Boeri, ‘there was a very important Triennale on reconstruction, then there was a very important Triennale in 1992 on the environment.’ One form of the Triennale came to an end in 1996. It was revived in 2016, in a massively expanded design world. That 21st edition was themed Design after Design, and included exhibitions exploring topics such as design’s relationships with anthropology, technology, art, craftsmanship and globalisation.

The more tightly themed Broken Nature followed in 2019, curated by MoMA’s Paola Antonelli, then in 2022 was Unknown Unknowns, whose main exhibition was curated by astrophysicist Ersilia Vaudo. Both featured contributions from numerous countries. They also embraced an enormous range of mediums, from traditional products to photography, film and installation. The Triennale today is less a design showcase than an application of design thinking to wider affairs.

The 24th edition will tilt at a constellation of issues that have become evident in the light of four crises that have shaken the complacency of the developed world: fundamentalist terrorism, the Great Recession, Covid-19 and the war in Ukraine. All of these have taken place against a growing awareness of environmental catastrophe and of societal inequalities, which are themselves connected. As Boeri expands: ‘The richest countries of the world contribute more than 40 per cent of the CO2 production. Yet the poorest parts are the main victims.’ He also wants the Triennale to look at the extreme divisions in resource ownership and healthy life expectancy across the world.

Photography by Annie Spratt, courtesy of Unsplash

Photography by Annie Spratt, courtesy of Unsplash

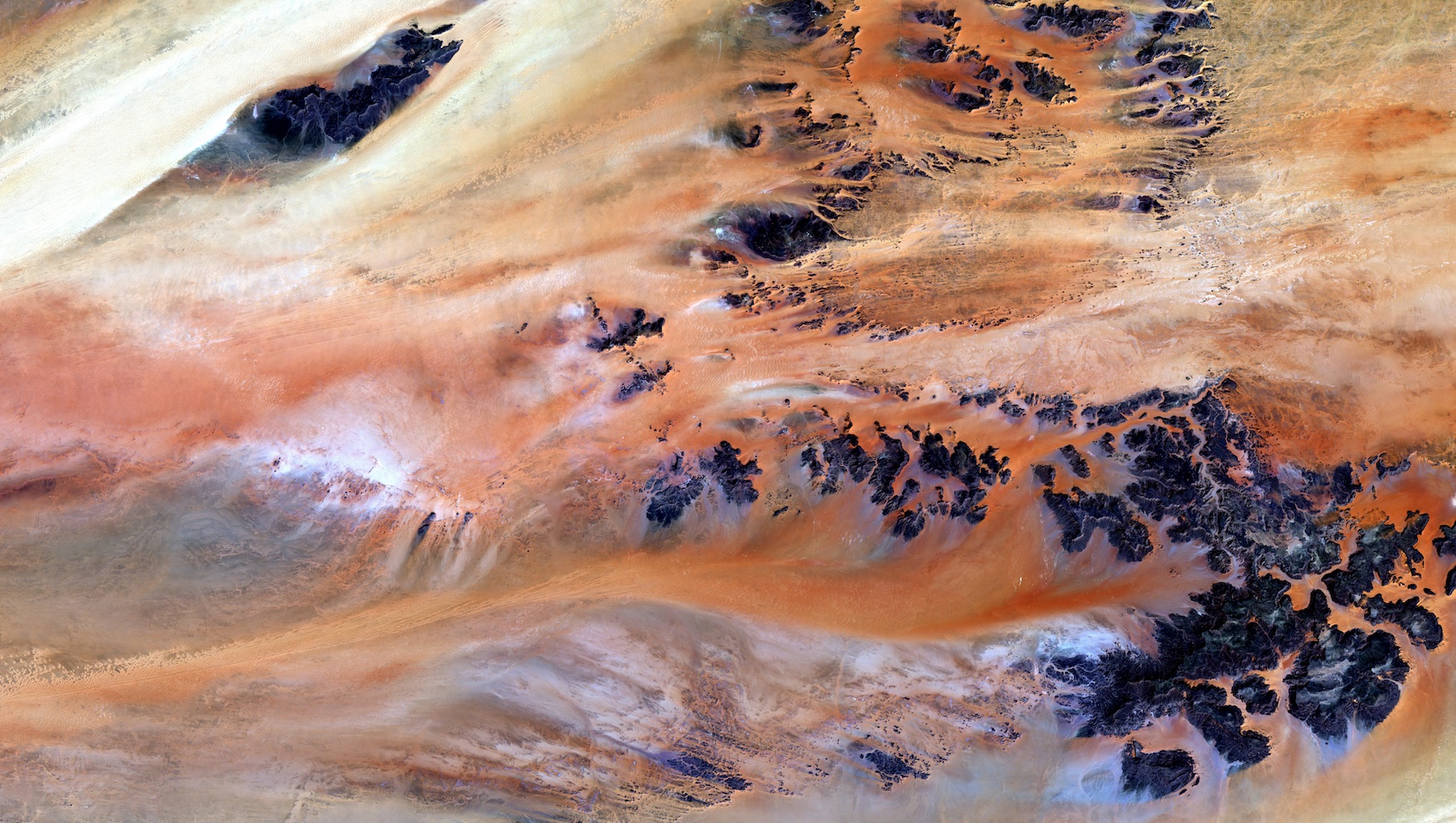

Boeri is interested in the ability of the more prosperous countries to react to ecological transition, and how that will shape the nature of the city. ‘If it’s true,’ he says, ‘that we are expecting 250 million people migrating from places of the world facing water scarcity and desertification, that means that the northern part of the planet has to deal with this issue.’ One-fourth of the world’s urban population is already housed in informal settlements such as slums and favelas. ‘This will grow,’ Boeri, ‘because we have no reasonable way to imagine how to host this process.’

The crisis-hit Inequalities might sound a far cry from the hopeful Triennales of the high modernist era. It matches our alarming age. ‘The future from over here,’ says Boeri, ‘is a disaster’. But we have to find ways to adapt. Boeri quotes the philosopher Antonio Gramsci’s dictum ‘pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will.’ However dark the world seems one should act as if the chance for betterment remains.

‘Design is always a little bit about what we have to do to solve issues,’ explains Boeri. ‘That’s why I believe design is an important voice when we talk about inequalities.’ Next year’s Triennale will hopefully provide ample notions to help create a more equal future, and forestall the worst consequences of climate change. ‘I’m optimistic,’ says Boeri, ‘about the final result of this atlas of inequalities — and an atlas of possible ways, tools, ideas and concepts that could help us face this issue.’

The story originally appeared in ICON 215, Spring/Summer 2024. Get a curated collection of design and architecture news in your inbox by signing up to our ICON Weekly newsletter