|

|

||

|

A nomination for the Mies van der Rohe prize is the latest in a string of accolades for the Irish practice’s LSE student centre in London. As the shortlist was announced last week, Icon met them to discuss their determined focus on context and consultation Just weeks after receiving the prestigious RIBA Gold Medal, Sheila O’Donnell and John Tuomey were nominated for another award – their Saw Swee Hock Student Centre at the London School of Economics is one of five building shortlisted for the Mies van der Rohe prize for European contemporary architecture. Icon met the Dublin-based husband-and-wife team at Europe House, the European Commission base in London, as the finalists were announced. ICON: You started out working in London before moving to Dublin, but you’ve worked all around Europe. Following this nomination, I wonder what you think of the idea of there being a distinctive “European architecture” and how national traditions fit into this? John Tuomey: We do believe there is a European tradition – there’s a European culture and character, which I think is more important than a national one. We are Irish architects, but we feel at home in Italy, in London, in Paris, in Budapest. From Ghent, to Porto, to Oslo, we always find practitioners with whom we have common ground and a shared culture. There’s a feeling of cultural depth in Europe that all architects know is a reality. Sheila O’Donnell: This prize gives you an opportunity to think about those connections – to see there are people all over Europe doing work that is related. ICON: What do you think makes the Saw Swee Hock Student Centre so successful? SO: We were trying to create a building that was specific to its context and in conversation with structures around it. We were also trying to make an open, lively environment with casual spaces where people could socialise and where informal learning could happen. It’s nice to go back now and see that it is being used like that – you find people having little seminars or just socialising. JT: I also think people enjoy the way the building relates to the streets and how it reveals the outer world through its openings. We took a motto of propagating the idea of street life, which meant there couldn’t be corridors, lobbies or divisional doors. You are able to walk through the building, from the door to the top floor café, without passing through barriers, like going down the street. We go to great lengths to make complicated things feel legible. Complicated buildings are more interesting, but they have to reveal themselves sleekly so people can get on with their lives. We hope that, when you go to one of our buildings, you are more aware of the view, light, the outlook than the building itself. SO: A lot of the work to make that happen is hidden. For example, it was a challenge making the fire escapes work in a way that left the main stairs open. One staircase had to go through incredible contortions to accommodate the hidden space. That isn’t part of your experience of the building, but it’s easy to move through it because these elements are out of sight.

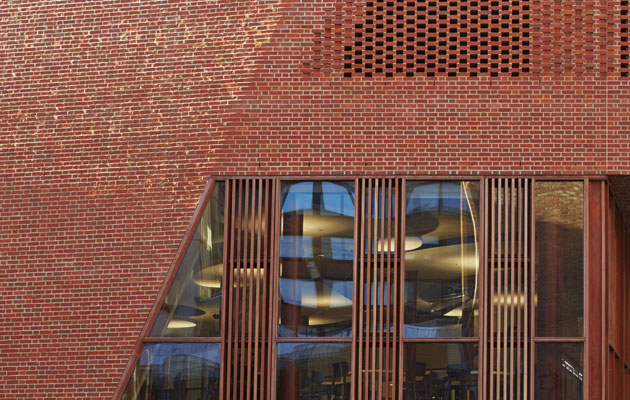

The Saw Swee Hock student centre at the London School of Economics ICON: The project was complex, both in terms of its narrow site and the complex brickwork. How did this affect the way you worked? JT: The restrictions on the site – in terms of property lines, rights of light and its density – were so many that we decided the best way to win was to yield, to just respond to every demand the site made, by leaning back or pushing aside. The result was a building that found its form by responding to its conditions, like it had evolved, or blown in the wind. The complexity of the brickwork slowed the whole process down. Because the bricks are visible from inside, outside, below and above, they had to be cleaned on all sides, and the different colours and shapes meant the bricklayers had to sort them as they went along. But I believe craftsmen like to rise to a challenge – if something is hard to do, the best person for the job will come along. ICON: What are you working on now? JT: We are working with Allies and Morrison and a small Catalonian firm called Arquitecturia on designs for the Olympicopolis, a cultural hub at the London Olympic park that will feature branches of the V&A, Sadler’s Wells Theatre, two universities and some residential scheme. We are one of six shortlisted teams. We’ve also started on site with the first of three phases of a campus masterplan for the Central European University, on a site in the centre of the historic city of Budapest facing the Danube. It’s a beautiful programme, which includes a library and auditorium and incorporates existing buildings and courtyards. We are also designing a student hub for the University of Cork.

Inside the Lyric Theatre in Belfast ICON: What lessons have you taken from your previous projects into these? SO: One thing we take with us is the importance of looking intensely at a place. We set out to make a fresh and different response to a context every time. JT: If you consider of the buildings we might be known for, like the Glucksman Gallery in Cork, the Lyric Theatre in Belfast, the Irish Language Cultural Centre in Derry – the first is timber, the second is brick, the third concrete and I don’t think they look like each other. We hope our buildings remind you not of each other, but of the place they are rooted in. We don’t want to just come along with one of our works and ask: “Where shall we put this?” SO: People need to know that you are making a building for them, not despite them. A lot of people think architects make buildings for themselves. What we enjoy is having a dialogue with the people who will use a building and making something that fits their ethos. For the Budapest project, we ended up having about 50 meetings with different user groups. In Cork, after we talked to the students, they organised an independent visit to the student centre at the LSE. They came back with lots of notes, for example, both universities have radio stations, but Cork’s is hidden at the end of a corridor. We put the LSE radio station on the stairs, as a kind of publicly visible broadcasting station and the students from Cork now want that too. ICON: What effect has your recent flurry of award wins and nominations had on your work? SO: SO: None so far, but it’s only been a few weeks since we won the Gold Medal. We are hoping to see its effects soon and that it will allow us to take on a big project that allows us to stretch a muscle we haven’t stretched yet. JT: We’d like to be able to work on a larger scale project, because we like to think strategically and sometimes that can be restricted by scale. |

Words Debika Ray |

|

|

||

The brickwork at the LSE