Amin Taha’s RIBA-nominated Barrett’s Grove project. Photo: Timothy Soar

Amin Taha’s RIBA-nominated Barrett’s Grove project. Photo: Timothy Soar

Architect Amin Taha weaves rich stories of time and place from rough-hewn limestone, terracotta concrete, and even basketwork. Just don’t call him a postmodernist, writes Tim Abrahams

Architect Amin Taha arrives carrying a pig’s head to our interview. He has been gifted the morsel following a client’s birthday at St John’s – that famous London architects’ hang-out where you drink a fair amount so you don’t mind eating the once fashionable offal that they still insist on putting on the menu.

He insists we reconvene at his favourite pub, the Three Kings, but before we are able to leave he receives a call that one of his buildings – 15 Clerkenwell Close – is on fire. His stoicism is impressive. Taha after all is designer, developer and soon- to-be tenant of the building. And although there are three fire engines outside the property when we arrive five minutes later, Taha’s phlegmatic response is proven to have been the right one when the issue turns out to have been nothing more than a pot on a stove.

New Clerkenwell classic

However, the window for the interview closes. Although the Three Kings is adjacent to 15 Clerkenwell Close, it takes a good hour for him to sort out the responsibilities of the fire service, the builders who are still completing some works and the security. The interview is effectively abandoned as he enters the Three Kings exhausted from his client’s birthday and negotiations with the building management software.

His last sober minutes are spent looking through the cast list of The Towering Inferno on IMDB. I leave Taha discussing stone masonry with the editor of this magazine: a subject about which they both clearly have very firm views. When he later returns to his wife and newly born son, he has the pig’s head in his possession.

The brick facde at Taha’s Barrett’s Gove project acts as a rain screen. Photo: Timothy Soar

The brick facde at Taha’s Barrett’s Gove project acts as a rain screen. Photo: Timothy Soar

As anyone who scrutinises his Stirling Prize nominated project at Barrett’s Grove rather than dismissing it as a bog standard infill set of flats will understand, Amin Taha is one of the most promising, interesting young architects working in the UK at the moment. His personal demeanour is gentle, although he is a constant engine producing ideas and stories.

His work sets him apart: a fundamental rejection of style as an orientating device in favour of structure. Remember the philosophical underpinning of postmodernism? The assault on the dominant narrative of modernism? Rather than the rehashed entablatures and arches? It suits Taha’s temperament. ‘I’d be terribly, terribly bored if I knew what I was supposed to be doing every day,’ he says.

From the Eastern Bloc to Edinburgh

At 16, his parents left their respective countries – his mother from Iraq, his father Sudan – to study medicine in East Berlin. Both countries had undergone socialist revolutions and sent students to the Eastern Bloc before undergoing counter coups which locked his parents out. Taha spent his first six years in Berlin before moving to the UK and remembers ‘books that demonised and promoted violence against the landowning classes that you weren’t even aware of’, as well as ‘red neckerchiefs for children born in the USSR while the rest of the Eastern Bloc kids were given blue and had to earn their red after years of pilgrimages to monuments.’

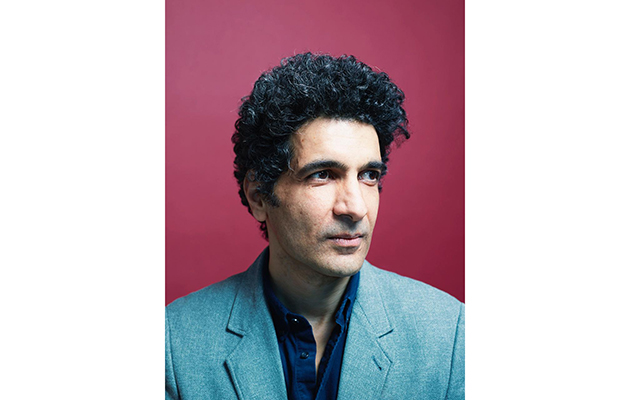

Amin Taha. Photo: Felicity McCabe

Amin Taha. Photo: Felicity McCabe

Taha studied at the University of Edinburgh under Isi Metzstein, who had also spent his formative years in Berlin and made the journey to Scotland in 1938 but for very different reasons. ‘He taught his students that no matter how complex the architectural intent, drawings should by their reworking say a great deal more than words alone,’ says Taha.

Metzstein who with architect Andy McMillan produced some of the greatest works of modernism to be built in Scotland, is a constant reference point for Taha who generally offsets his clear respect for the master by mimicking his singular German Jewish Scottish accent. ‘Without learning our craft we will be dictated to and damaged by the arrogant and uneducated,’ he says at one stage in our conversation.

Hadid’s excellent eye

Taha certainly learned his craft. On graduating, he worked for Zaha Hadid Architects on the Maxxi project in Rome. He has stories of working under Zaha; some of which he refuses to repeat on record. He will say that she had an excellent eye.

‘This was ably demonstrated during lunches when, for instance spotting at the far end of the office the first and unsatisfactory draft of a winter facility, she sent her criticism in the form of a speeding tomato which splattered across the screen and its operator,’ he says. And yet he clearly brooked against the totalising style and the way it both ignored the space between structure and the professional relationship between architect and engineer.

RIBA Stirling prize nominated

Structure and process are the means by which he breaks through the narrowness of a given style. Barrett’s Grove, for which his practice was shortlisted for the RIBA Stirling Prize, is one example. Most commentators missed the subtlety of the project, which was in fact constructed from cross-laminated timber (CLT) modules, creating both structure and interior finish.

The building was clearly misconstrued when it was used to illustrate a feature in the Architectural Review that criticised the tasteful restraint of architects in London when it came to ornament and specifically their tendency to ‘present applied panels and materials as if they were structural’. If you look closely at the screen of the elegant series of apartments on a tight site, the envelope of double-stacked or open-bond brickwork is regularly perforated. It is not load bearing but a six-storey rain screen separated by a 150mm void from the CLT structure.

Clerkenwell Close has a structural stone exoskeleton. Photo Timothy Soar

Clerkenwell Close has a structural stone exoskeleton. Photo Timothy Soar

In fact, Taha’s work is a qualified assault on the tendencies attacked in the AR article. At 15 Clerkenwell Close, it was the main animus to the design. ‘The problem with most stone structures in the UK – probably pretty much everywhere – is that it’s all stone tiles.

For maybe 60 years we’ve all got used to concrete or steel superstructures and vast amounts of layering and insulation and fireproofing on rails and ultimately the stone is like bathroom tiles clipped on to the superstructure,’ says Taha.The stone columns and beams that form the exoskeleton of the building are loadbearing and refer, as per the insistence of heritage officers, to the stone of the Church of St James opposite, which was built in limestone by the Normans in the 12th century and rebuilt at the end of the 18th century in its present Georgian form.

‘Clarity of intent’

Following the seam of limestone from the nearly exhausted quarries in Portland to northern France (the region from where the Normans came), Taha noticed that some of the limestone was textured with fossilised coral. The quarry master said that they normally cut it off and crush it for road surfaces.

Taha also noted how hand and machine cutting techniques textured other facets of the stone slabs and resolved to include these as well. Hence the crenelated, fragmented texture of the building, which addresses St James’ like a severed stratum of stone reaching back in time. The exoskeleton is linked to the floors from by a galvanised steel boss which is mortared into a carved pocket where columns and lintels meet. It is bolted through a solid nylon plate, providing thermal isolation, to a female galvanised steel plate cast into the concrete slab. It is not some kooky structure but a well-engineered one.

Certainly the external effect is aesthetically disconcerting and likely to confound many who pass it. Is this all just a game? Taha insists not. ‘Our postmodern time should be a liberation from every generation having to follow a pre-prepared style.’ His goal he says, quoting Le Corbusier, is ‘clarity of intent’.

Taha’s Upper Street project now houses the Aria store. Photo: Timothy Soar

Taha’s Upper Street project now houses the Aria store. Photo: Timothy Soar

He admits that this is made harder by every author being responsible for their literacy. However, designers must embrace this freedom. For him it all begins – unfashionably – with the way in which a building stands up. ‘Structure is integral, all architecture has a narrative. Materials and their structural possibilities are the vocabulary, syntax and grammar of architecture,’ he says.

Everyone is about the process today. Some more than others. ‘There’s a commonality in the process from one project to another, but the product at the end isn’t always the same.’ The many fans of his work tend to agree.

In-situ terracotta concrete platforms

On Upper Street in Islington, he returned to an idea that had originally emerged for an unbuilt project on Bayswater Road of designing a ‘ghost’ corner block for an incomplete 19th-century neo-classical facade. In this case, it was the ‘missing piece’ of an Islington terrace that had been bombed in the Second World War. Yes, Edoard Francois used a similar strategy at the Hotel Fouquet in Paris in 2007 but Taha has given the idea a rigour that Francois’ – otherwise impressive – project lacked.

For example, it is not simply the outer walls that have been cast but the roof and the inner walls too (anaglyptic wallpaper reliefs are found throughout the interior). In addition, the in-situ cast ‘terracotta’ concrete performs not simply as a facade but also as a loadbearing structure and as a thermal envelope, complete with external and internal nishes. His team pushed the boundaries of in-situ formwork. Instead of using plywood coated in a phenolic resin they experimented with routed expanded polystyrene and calculated the cost of applying that to low-grade plywood.

‘Of course it is far more flexible to receive any form of design we wished to carve into it than attempting to fabricate formwork for precast panels,’ says Taha.

The rich palette in Diamond Hammered House in Bayswater include cherry wood and concrete. Photo: Timothy Soar

The rich palette in Diamond Hammered House in Bayswater include cherry wood and concrete. Photo: Timothy Soar

His ceaseless search for a new idea is impressive; a rejection and running away from received wisdom. It is noticeable that unlike most practices one engages with as a journalist where the junior members of the team keep their heads down, Taha’s have their own opinions which they aren’t afraid to give.

His practice operates under the aegis of Groupwork, which is an employee ownership trust that makes Amin Taha Architects an equitable partnership. He practises what he preaches, which isn’t always easy.

‘If you are worried about your own skills, go with classicism’

Speaking alongside proponents of postmodernism and classicism at a balloon debate at the University of Westminster in 2016 he made a passionate case to reject all styles. He stated boldly to the audience: ‘Do you really want to tell someone for the rules?’ He then made a tactical error by adding, ‘If you are worried about your own skills, go with classicism.’

When it came to the public vote, classicism won by a considerable margin. Originality requires a certain bravery and a certain – dare one say it – pig-headedness.