Normandie in New York 1935 39, photo courtesy of Collection French Lines

V&A’s exibition reveals Ocean Liners as the most intense, total works of art that our culture has ever produced, writes Edwin Heathcote

Ocean liners, we are told, were the epitome of style. This was the golden age of glamour, the moment at which heavy industry and design came together to create the greatest machines ever made.

This was the age of the luxury liner, the endless choice of increasingly luxurious restaurants, of gowns and dinners and deckchairs, an impossible lost world of unbelievable elegance in which every detail was handcrafted and every whim catered for. And that is pretty much the line the V&A feeds us here, in the tenth year of austerity and in the era when Britain is pretending it can somehow regain its one-time status as a seafaring superpower.

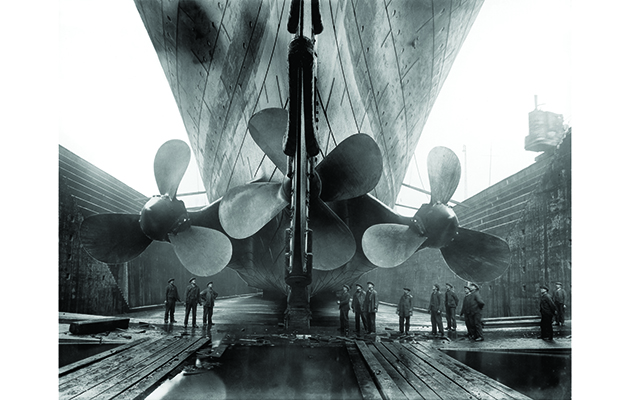

But there is another point of view. Paul Virilio famously pointed out that the invention of the ship was also the invention of the shipwreck, that each new technology or archetype carries within it the germs of newer, bigger, better disasters. And here, of course, in the V&A is a fragment of the Titanic, floating on a fake sea of gentle ripples and lent by the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic in Halifax, Nova Scotia. There is also (as if we needed better Brexit metaphors) a deckchair, rather lumpy and wooden, its wicker seat smashed.

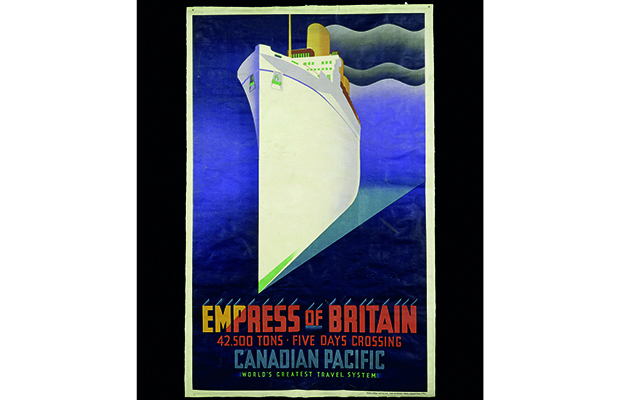

Empress of Britain colour lithograph poster for Canadian Pacific Railways by J.R. Tooby London 1920, courtesy V&A

The ocean liner was, I’d suggest, not only the zenith of the age of making, of design, industry and craft, but also the harbinger of the contemporary built landscape. You can see it as you move around the exhibition. Designers desperately looking for ways to make their new dining rooms, cocktail lounges and lobbies look even more glamorous, even more excessive.

There are drawings by Mewès and Davis who designed the Ritz, and by Bruno Paul, there are chairs by Gio Ponti and Ernest Race, there are interiors by Hugh Casson and Edward Bawden and one decorated by David Hockney. These were oating showrooms of contemporary art and design. But look at where it led. Today’s cruise ships (which are oddly absent here, as the show is sponsored by Viking Cruises) are oating palaces of kitsch, carefully designed to impart the sensation of luxury to a mass market.

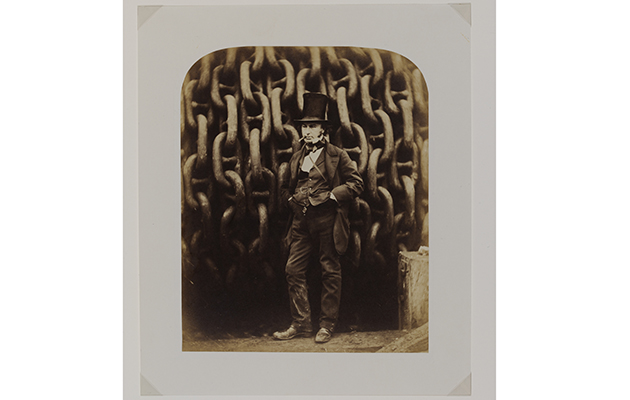

Isambard Kingdom Brunel and the launching chains of the Great Eastern Robert Howlett United Kingdom 1857, courtesy V&A

They are almost inseparable from casinos in Vegas, hotels in Dubai or rst-class airport lounges in Singapore. The ocean liner is the genesis of the deracinated global-corporate architecture of luxury which has become the aesthetic language of the contemporary city. It has nothing to do with its context because its context is the ocean, it is completely internalised except that it uses the view as another mode of consumption. It is an architecture of self- containment through necessity, just as is the shopping mall, the airport or the US conference hall and hotel complex.

None of this, of course, is to blame the ocean liners. They, as this show reveals, really were the ultimate 20th- century Gesamtkunstwerk, the most intense crafted total works of art that our culture has ever produced. There is a short video playing on a loop of ships under construction in the Glasgow shipyards.

Silk georgette and glass beaded Salambo dress Jeanne Lanvin Paris 1925. Previously owned by Miss Emilie Grigsby. Courtesy V&A

Men in at caps and baggy trousers smashing in red-hot rivets and bashing metal panels to create the smooth, streamlined pro les of the liners’ hulls. It’s a moment of quite intense dislocation, a little jolt that pulls you out of the over- glamourised glamour. The clips are too short but they do the job. This was the tail-end of heavy industry in the West and the ships were a swansong, a nal, joyful expression of what mankind was capable of making.

The narrative of the exhibition is something rather different. The underlying (and undeniable) thesis is that these ocean liners were expressions of national ambition. The British, followed by the French and then the Germans, competed to make the biggest, the best, the fastest and the most ships.

For the British it looked like an escape, a way out of the polluted cities to somewhere exotic, the parts of a slowly shrinking empire from where Britain could still be looked back on with a sense of nostalgia. Look at Edward Bawden’s Country Pub mural (for Cunard’s Oronsay) – all thatched roofs, wheat sheaves and village churches.

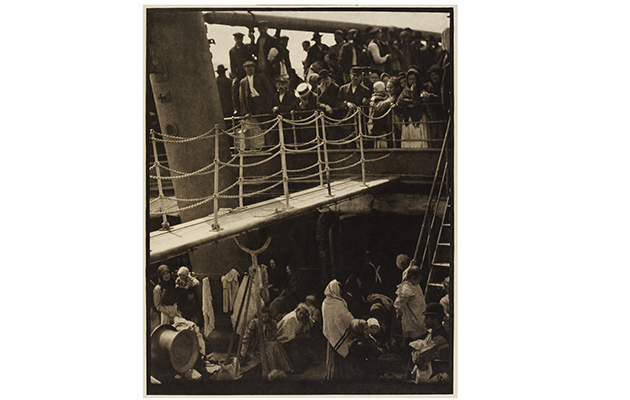

The Steerage Alfred Stieglitz 1907. Gift of the Georgia OKeeffe Foundation. Courtesy V&A

For the French they were floating trade fairs for the luxury industry. French liners, most notably the astonishing Normandie (1935), were an expression of France’s status as the spiritual home of art deco (nervous as they were about the US doing it bigger and better), a statement about modernity and France’s continuing relevance through design, craft and sheer good taste.

For the Germans it was about speed, about snatching the Blue Riband (the award for the record speed from Europe to the US) away from Britain and asserting its industrial and engineering supremacy. Note, however, that most of these ships were sailing from Europe to New York – these were old-worlders, nervous about their declining status, making their way to the future on the other side of the Atlantic. The whole phenomenon could be read as a huge existential scream of insecurity expressed through the most exquisite means of denial.

Titanic in dry dock c. 1911

This is billed as the first blockbuster show of ocean liners, which seems surprising. The big ship has become such a potent metaphor in contemporary culture, the Titanic, icebergs, deckchairs, the Poseidon, the lost glamour and the Saga romance, that it seems remarkable it hasn’t been explored before. There are fascinating asides here too.

One small space is dedicated to the architecture of the shipping companies: big, beaux arts buildings often constituting whole streets or ensembles (London’s Cockspur Street and Liverpool’s waterfront), all constructed from proceeds of the ocean liner boom (and more particularly from the desperation and misery of hopeful emigrants squeezed into the stuffy spaces below in the earlier ships). Most impressively there is the wall of posters which are themselves brilliant artworks, an industry predicated on the glamorisation of glamour, all looming hulls and skyscrapers.

Ocean Liners: Glamour, Speed and Style

V&A, London

Now until 17 June 2018