|

|

||

|

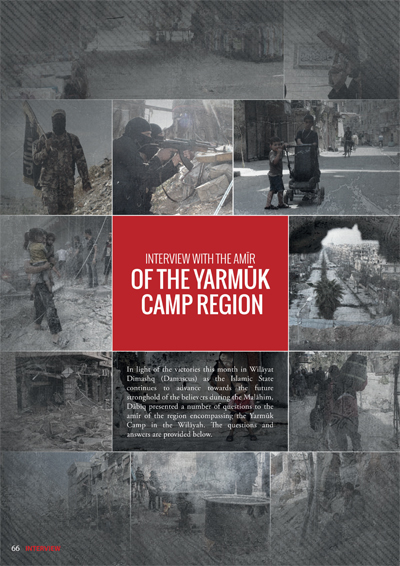

As Islamic State releases another issue of its radical publication, counter-terrorism analyst Artur Beifuss takes an expert look at how the group has designed the magazine to shape its image and reach its target audience As a radical and extroverted subculture, the Islamic State wants to be understood by its followers as much as it wants to terrorise perceived enemies. As a brand, it has a lot of explaining, positioning and justification to do. The Al Hayat Media Center, the media wing of the group, publishes a full colour magazine of on average 61 pages and digitally distributes it in PDF format to an English-speaking audience in Europe and the United States.

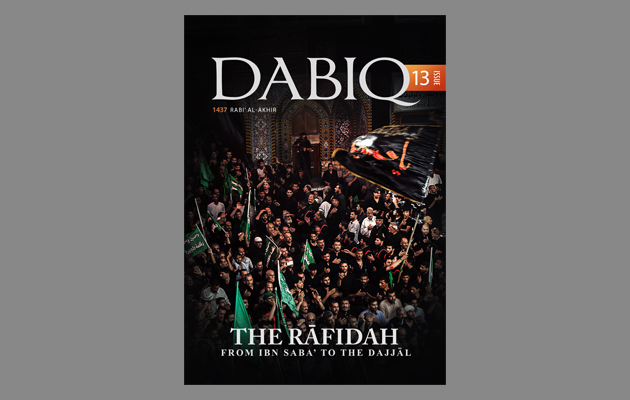

The Al Hayat Media Center is the group’s media wing The name of the magazine, Dabiq, refers to a village in northern Syria where the Islamic State believes there will be a decisive fight between Muslims and its enemies shortly before the world ends. Since July 2014, the magazine has been irregularly published 13 times. The most recent issue – released this month – praises the San Bernardino attacks in California, justifies the killing of Shiites Muslims and Saudi clerics and features a two-page obituary of the assassin “Jihadi John”. The previous issue, released five days after the terrorist attacks in Paris, had on its cover a photo of a victim being taken to hospital and the simple line: “Just Terror”.

Issue 12 appeared five days after the terrorist attacks in Paris Despite wide international coverage of their actions, IS seems to believe that the timely production of its own, relatively complex, magazine will demoralise its perceived enemy and boost the morale of its supporters and sympathisers. While the international media frames the Islamic State in negative terms, the Al Hayat Media Center counters this by providing an explanation of its religious, political and military vision, thoroughly referencing its interpretation of Islamic scholarship. Dabiq is not only news – it is public relations. |

Words Artur Beifuss

Above: The cover of the latest issue of the magazine, released this month |

|

|

||

|

The magazine’s conventional layout resembles that of an in-house company magazine

Certain quotes and phrases appear in each issue |

||

|

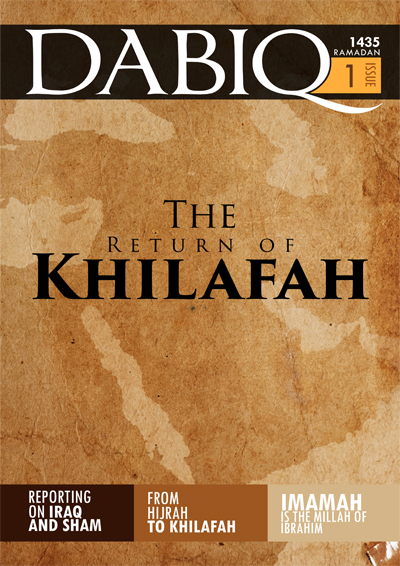

The first issue appeared in July 2014 and featured the cover line: “The Return of Khilafah”. It emerged at a crucial time in the organisation’s history – five days after the militant group formerly known as ISIL or ISIS declared a caliphate and changed its name to “Islamic State”. The cover featured a map of the Arabian peninsula without the borders separating the nation states. “The spark has been lit here in Iraq, and its heat will continue to intensity – by Allah’s permission – until it burns the crusader armies in Dabiq,” says Abu Musab Al-Zarkawi, the founder of the group – a strategic message that is featured in every issue.

The cover of issue 1, published in July 2014, features a map of the Arabian peninsula without the borders separating the nation states |

||

|

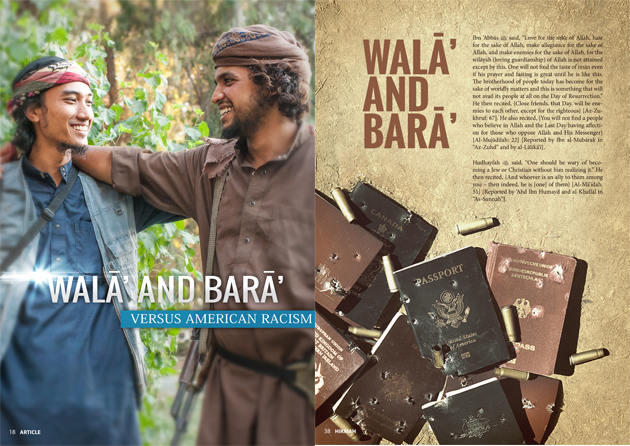

Such messaging, codified language and adherence to a strict narrative is essential for any subculture and is often used by members of such groups to differentiate themselves. The articles in Dabiq push the “us vs them” narrative and are labelled with (anglicised) Arabic terms relating to Islamic concepts. Dabiq is, in many ways, an exercise book that helps western readers in the use of untranslatable Arabic terms and Islamist concepts. |

||

|

The articles push the “us vs them” narrative and are labelled with Arabic terms relating to Islamic concepts |

||

|

Crucially, Islamic State is communicating with a globalised audience – in a world defined by images, with a high demand for visual narratives. Meanwhile, its philosophy is based on radical interpretations of text-heavy Islamic and Islamist sources – commonly published in Arabic. Only a fraction of those works is available in European languages. Dabiq’s solution is to aggregate translated Islamist content and narrate them in relation to pop culture – for example, by referencing cinematic composition and graphic novels in its layouts. Striking, high-resolution images, carefully selected with attention to lighting and perspective, are another response to the universal shift from presenting information through text to speaking through images.

|

||

|

|

||

|

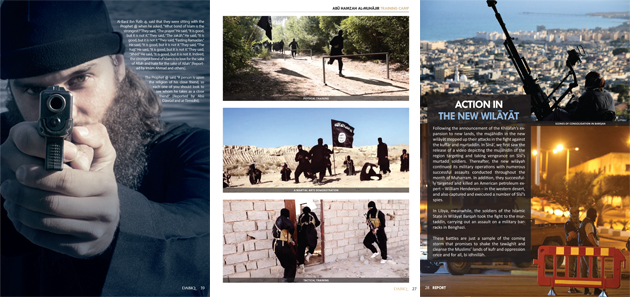

Layouts take inspiration from Hollywood cinematography, graphic novels and television news coverage |

||

|

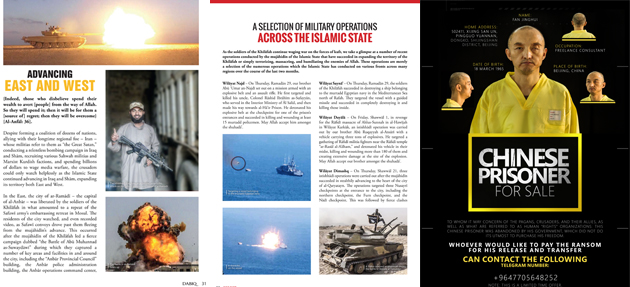

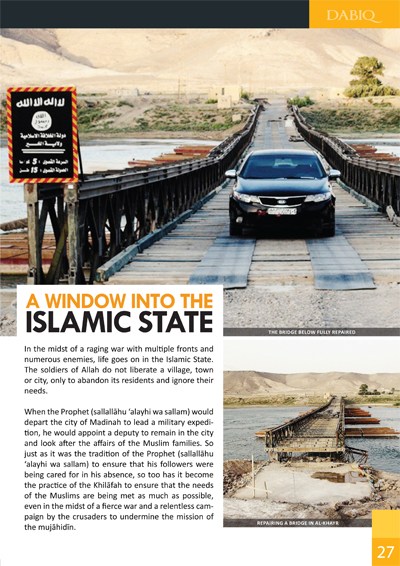

At the same time, Dabiq’s layout is never really innovative or playful. Its format is close to that of many organisations’ in-house bulletins and newsletters. The typographical execution is not perfect and, in comparison to many western magazines, it features large amounts of text – normally arranged in two columns. But the images it uses are unambiguous and explicit, standing in direct relation to the message of the story it illustrates. Enemies are covered in blood or dead, the photos of opposed political and religious figures are often unflattering, while Islamic State fighters appear holding weapons – heroic, determined and always ready for victory. Islamic State does not only want fighters – but doctors, engineers and other professionals, too. The choice of imagery illustrates that, providing the impression of a functioning state that covers all social needs.

A report on IS repairing a bridge: such features create the impression of a functioning state covering all the needs of society |

||

|

Islamic State not only want fighters but also doctors, engineers and people with other professions |

||

|

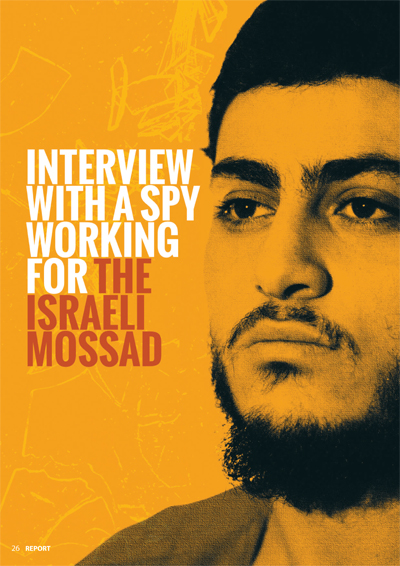

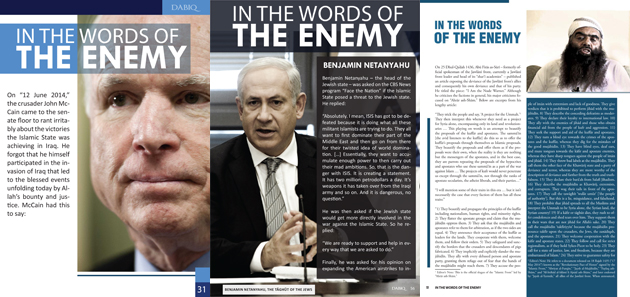

The lack of innovation in design is countered by innovative ways of presenting content – features often come from unusual perspectives, including the section “In the words of the enemy”, articles written by the captured British journalist John Cantle and interviews with “captured spies”.

|

||

|

Articles often have unexpected angles, such as the “In the words of the enemy” feature and interviews with spies |

||

|

Another innovation is the way it references online content: one feature, “Selected10”, is modelled after a recommended playlist and provides readers with a ranking of the best videos produced by followers, supporters and recruits over the past month. There are screenshot previews of its favourites – like on a DVD. Often full-page adverts announce feature films or documentaries – if they are in Arabic, instructions for downloading and enabling subtitles are included. |

||

|

From left to right: An advert for a documentary, a selection of the editors’ 10 favourite recent videos and instructions for downloading films and enabling subtitles |

||

|

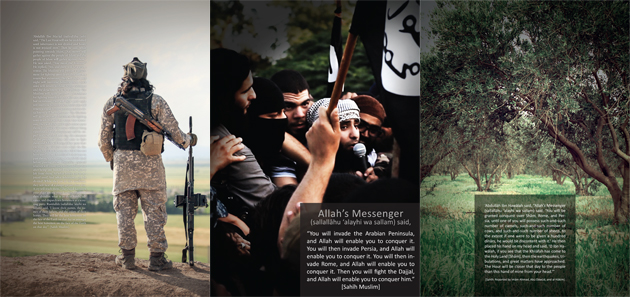

The last page of each magazine directly addresses the reader, calling on them to join IS’s cause. Horizons or nature scenes suggesting peace and paradise are flanked by encouraging quotes guaranteeing “the support of Allah”. This, the last page, is where readers pictures themselves and contemplate their role in this world. |

||

|

The final page of each magazine calls upon the reader to join IS’s cause |

||

|

In an information-saturated society, the challenge is to communicate with an authentic voice. Authenticity is not about the Islamic State being right or wrong – rather, it is about whether the magazine’s readers believe it is faithful to its own objectives and supporters. Dabiq demonstrates a disciplined approach to building a brand of jihad. At a time where 90 percent of terrorist recruitment happens online, the Islamic State has mastered the professional presentation of extreme content for an image-hungry western-educated audience. The juxtaposition of considered design and radical content surprised many observers from Europe and the US, where radical content in print has traditionally been distributed in the form of flyers, leaflets and similar amateurish produced and reproduced underground documents. Dabiq is not perfect, but it is serving its purpose with increasing efficiency. |

||