|

|

||

|

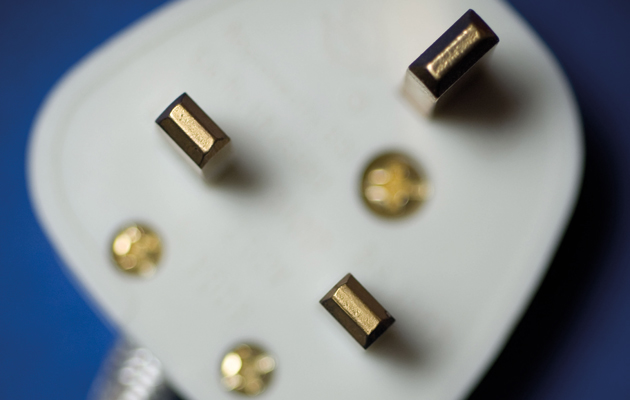

It may not match today’s svelte digital parts, but our sensible approach to wiring is something to be proud of, says John Jervis In a relaxed, cosmopolitan office such as Icon’s, there’s one subject that ensures outbursts of complaint from foreign colleagues: the sheer size and unyielding plastic bulk of the British plug. Its capacity to inflict extreme pain when trodden upon is merely an aggravating factor. Such criticism has always seemed a little ungenerous, and not just due to some innate nationalism on my part. True, the BS1363, long regarded as the safest plug around, cannot match today’s svelte digital parts, but neither does it have the flimsy, uninsulated tin-foil pins of US equivalents, nor the convenient road to suicide offered by ill-matched continental alternatives. Some new plugs are equally risk-averse (and equally chunky), but this satisfyingly solid piece of electrical infrastructure is no Johnny-come-lately. Its design, and that of its accompanying socket, began life almost three-quarters of a century ago, closer in time to Edison’s light bulb than today. Economic imperatives drove the development of American and European electrical infrastructure, ensuring the hasty adoption of pre-existing commercial components and barely compatible standards, many still in use today. In contrast, the BS1363 resulted from state intervention in energy supply, a British tradition that dated back to the establishment of the National Grid in 1926. The BS1363, like the Beveridge Report or the County of London Plan, was a product of state planning for Britain’s reconstruction after the Second World War. In 1941, committees were formed to publish Post-War Building Studies in areas ranging from fire-grading and farm buildings to school equipment and sound insulation. They came under the aegis of John Reith, the minister of works and planning, who had previously established the BBC with a similarly paternalistic vision. Free of commercial constraints, the Electrical Installations Committee was able to pursue the safety and convenience of a single standard: an earth conductor with a large pin and relaxed wire; flat, polarised live and neutral pins; a flush-fitting casing with a grip and bottom-entry cable; a shuttered, earthed socket. Economy was another concern: the inbuilt fuse improved safety but also allowed for ring circuits, saving on expensive copper while future-proofing housing stock against a postwar proliferation of sockets. It may seem banal, but this piece of hard plastic, these shared electrical wires, give me a powerful sense of home, of belonging to a collective far more vital than one founded on Tulip chairs or Eames loungers – and one which coincides with its unfashionable progenitor: the nation state. The BS1363, despite being introduced as Orwell drafted 1984, is proof that interventionist planning can work for the benefit of all. This is design that matters. And, almost 75 years later, it works. |

Words John Jervis

Above: The three-pin BS1363 has been the universal plug for domestic and commercial use in the UK since 1947 |

|

|

||