|

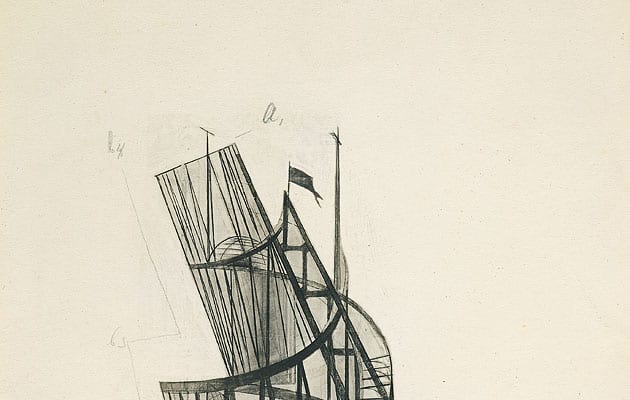

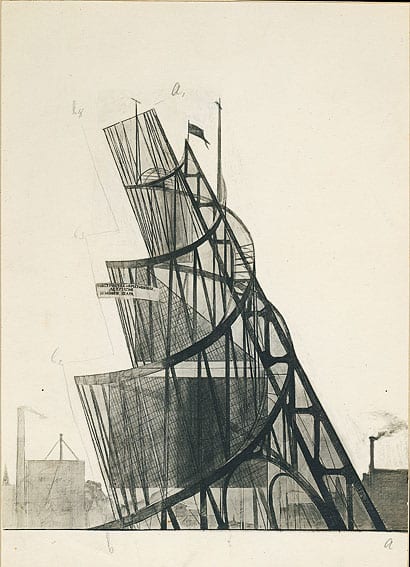

Drawing by Tatlin of his proposed tower, published in Nikolai Punin’s 1920 book The Monument to the Third International (image: © Punin Archive, St Petersburg) |

||

|

The Monument to the Third International – better known as Tatlin’s Tower, after its creator, Vladimir Tatlin – is one of the most influential structures never built. If it had been built, 2009 would be its 90th birthday; but even as an unrealised plan, the tower was a powerful presence in the art and architecture of the 20th century, and casts a long shadow into the 21st. The tower was revolutionary in every respect – and almost unimaginably ambitious. Before the overthrow of the Tsar in 1917, Tatlin was an artist, a leading figure in the abstract movement that would later be known as constructivism. In 1918 he was appointed to head the arts division of Narkompros, Lenin’s national education committee. Given the job of replacing Tsarist monuments, Tatlin devoted himself to trying to establish what revolutionary, socialist monumental art should look like. Tatlin’s thinking meshed with the emerging ideals of constructivism. He and his colleagues were inspired by the functional beauty of the machine – by industrial structures, by plain shapes and forms, by electrification, by flight, and above all by movement and dynamism. The monuments of the new era, they said, should be functional and active, not sullen objects for veneration. In 1919, it emerged that Tatlin was synthesising these ideas into a major monument to the revolution, probably intended for St Petersburg. In the spring of that year, Trotsky founded the Third International, an organisation devoted to spreading the revolution abroad, and a description of Tatlin’s Monument to the Third International appeared in the press. The monument – which would also be the International’s headquarters – would consist of a mighty steel girder thrusting 400m into the air at a 65 degree angle from the horizontal. Two ascending spirals could intersect with this spine, forming the body of the structure. Inside the spirals would be three glazed volumes: a cube with space for holding conferences and congresses at the bottom; a pyramid with administrative offices in the middle; and a cylinder with information and propaganda services at the top. These internal volumes would rotate at different speeds, marking days, months and years. The tower would serve as a radio mast and a bridge over the Neva river; slogans would be projected from it onto the clouds. And, true to its resemblance to a giant telescope, it would act as a kind of astronomical instrument, with its spine aligned to the Pole Star. It was visionary, and it was doomed. Although a panel of engineers stated in mid-1919 that the structure was technologically feasible, it was a practical impossibility in a state gripped by civil war. The tower languished, but as late as 1925 its model was being exhibited, suggesting that construction was still a possibility. When stability did return, however, it was under the Stalinist despotism. Stalin had no time for the constructivist avant garde, preferring to dream of swollen baroque wedding cakes such as Boris Iofan’s Palace of the Soviets. Tatlin was sidelined, and died in 1953. Tatlin may be gone, but his tower lives on. It’s the subject of a major new study by Norbert Lynton, published by Yale University Press this year, on the heels of historian Svetlana Boym’s 2008 exploration of the tower’s influence on 20th-century art. And the tower persists in architectural myth, a symbol of promises and dreams that have haunted the profession for the past hundred years – and haunt it still. It foreshadows the utopian techno-fixes of Buckminster Fuller – oddly, like Fuller, Tatlin devoted much of his career to a fruitless search for a personal flying machine. In its dynamism, its longing for an architecture of action, the tower could be a prototype of the designs of Archigram or Cedric Price; with its exposed structure and mechanism it points towards the high-tech of early Rogers and Grimshaw. When Rem Koolhaas unveiled his Prada Transformer earlier this year (icon 073), it seemed a nod to Tatlin’s tower: a dynamic, functional structure defined by platonic forms. Koolhaas, of all contemporary architects, seems to be the most influenced by Tatlin – he shares his restlessness, his polemical approach, his enthusiasm for technology and his eagerness to break with the junk shop of the past. The name Tatlin has come to be associated with the failed utopianism of the 20th century. But he is also an appropriate avatar for the promise of our own century.

Drawing by Tatlin of his proposed tower, published in Nikolai Punin’s 1920 book The Monument to the Third International (image: © Punin Archive, St Petersburg) |

Words William Wiles |

|

|

||