A self-taught photographer, Paolo Monti became the great documenter of post-war Italy, from the elegiac decline of Venice to the abstract geometry of Milan, writes Joe Lloyd

It’s a house that would stump even Monsieur Hulot: constructed on a series of uneven levels, with archways within archways and an external stairwell rising from an invisible landing. Photogaphed in black and white, it has a clay-like squidginess. A man gazes out of a window and children play in the foreground, but it is the building that pulls focus, simultaneously too strange for this world and bearing the marks of heavy use. We are on Procida, an island in the Bay of Naples, and this is a shot by Paolo Monti (1902-82), perhaps Italy’s greatest post-war photographer of buildings and cities. In further images of Procida, similarly gloopy buildings are chopped up into close-ups, becoming almost abstract collages of buttress and arch.

Monti’s early life was the conventional one of the early 20th-century northern Italian professional class. He spent his childhood shuffling around Piedmontese towns following his father’s banking work; that father was himself a keen amateur photographer, and Monti grew up surrounded by cameras and their accoutrements. After graduating from Milan’s Bocconi University in 1930 with a degree in political economy he settled for a similarly itinerant bourgeois lifestyle, moving with each job. Then, in 1945, after getting a job with the Veneto Agricultural Cooperative, he came to Venice.

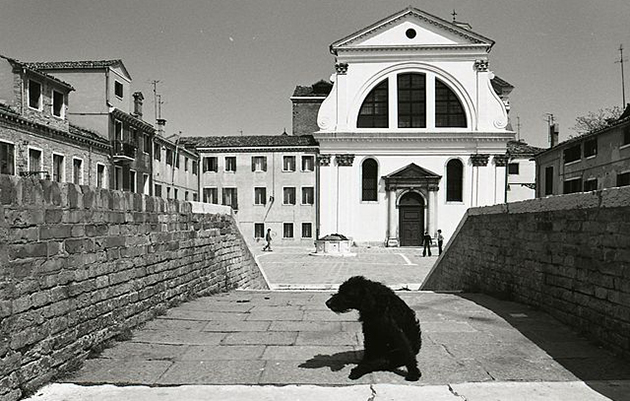

The most serene republic awakened Monti’s sensibility to architecture and city. Inspired by his friend Ferruccio Leiss, who had made a series of penumbral views of the city at night, he looked for a Venice away from the monumental basilicas and palazzi – one of crumbling walls, murky doorways and ragged backyards. One picture shows a scrap-strewn alley so shrouded in shadow it becomes almost a cavern. At its terminus, a small square of line reveals an elderly-seeming man, who limps before the portal of the San Michele cemetery. In another, a similarly ragged calle leads from an ornate courtyard, with sculptural walls and an decorative cherub. These photos emanate an elegiac decline.

Monti was the sort of amateur that makes professionals anxious. He would cut out photographs from the magazine Das Leben and bind his favourites into wordless photo books. He wrote numerous articles for photographic journals. Inspired by the likes of Otto Steinert and Minor White, he dabbled in abstraction; his Torn Poster series, showing tears and fissures in wall-size advertising sheets, remain disconcerting.

In late 1947, in response to the founding of Giuseppe Cavalli’s La Bussola (“The Compass”) group, he instituted his own club, La Gondola. Monti and his companions aspired to be independent of the dominant trends in post-war Italian photography: the rigorously ordered, aesthetically led formalism epitomised by Cavalli, and the gritty verisimilitude of neorealism. The Gondola instead lionised freedom – and indeed Monti’s oeuvre is so varied it is hard to pin it down.

It took until 1953 for Monti to go professional. He moved to Milan and quickly established himself by illustrating articles for Domus, Casabella, Style & Industry and many more. He was an official photographer of the X Triennale

di Milano. In the bomb-ravaged but resurgent Lombard capital, Monti found a modern city every bit as strange and labyrinthine as medieval Venice. He documented the post-war neighbourhoods of San Siro and the QT8, the latter of which included the first prefabricated houses in Italy, and the growing cluster of skyscrapers poking between historical corsi and piazzi.

In one photograph, he captures Luigi Moretti’s bathetically named Palazzo Multifunzionale, a mixed office and residential building, as a prow-like extrusion sailing off into the quay; squint, and it could also be a black-and-white suprematist construction, assembled from geometric shapes. Monti photographed Gio Ponti’s Pirelli Tower from almost every possible angle, including from a moving train. From close-up, it becomes a monolithic knife rising up the sky.

After being invited, in 1966, to document the historic centre of Bologna, he became Italy’s go-to photographer-conservationist, studying town after town. Not coincidentally, this led him to shadow Carlo Scarpa as he worked on some of his most significant projects, including Verona’s Museo di Castelvecchio. But his work never became dull, and he continued to dabble with unconventional forms like phonogram and chemigram. In 1982, the year of his death, Monti returned to Venice. A chromogenic print of the Arsenale façade, guarded by ornamental lions, is worn down but standing firm: testament both to Monti’s aesthetic of decline and his ethos of preservation.