words Justin McGuirk

portrait Emanuel Bras

Fernando Brizio is meticulously inserting coloured felt-tip pens, nib down, into a white dress fitted with little pockets for that very purpose. The ink is bleeding into the fabric in a rhythmic sequence of splodges. “I remembered that birds of paradise change shape and colour to seduce other birds. I think it’s more or less the same,” he says, recalling the genesis of this design.

As Brízio works his way across the dress, his expression oscillates between studious concentration and impish mischief. There is something in the Portuguese designer – not so much a resemblance as an attitude – that keeps reminding me of Harpo Marx.

Although he won’t admit it, Brízio has a talent for slapstick. Accidents crop up everywhere in his work – deliberate ones. The idea behind the dress, for instance, is that the owner slips the pens into the pockets herself just before entering the party or whatever she’s attending and bursting into messy bloom. It’s as much a happening as a dress (and the ink washes out, so it can keep on happening).

Brízio is Portugal’s best-known product designer, and yet his modesty in acknowledging this fact – “Oh… thank you” – only serves to prove what a meaningless accolade it is. His Painting a Fresco with Giotto bowl – crowned with a ring of felt tip pens seeping ink into the ceramic – brought him to momentary attention in 2005, yet he remains a marginal figure. Despite a distinctive take on the world and a body of catchy work, he is not well represented in print. Many designers have made a lot more out of much less.

The day before he inks up that dress – in a photographer’s studio – Brízio drives me to his workshop, which he shares with a set builder, in a former factory in the south of Lisbon. He flicks the light switch and smiles apologetically. It looks like a bombsite. The contents of an exhibition in Turin have just been returned to him and are scattered across the floor in half-open boxes spilling styrofoam packing beads. Plus there are cans of spray paint and felt-tip pens everywhere. There are no assistants to be seen because he works alone.

Brízio is startlingly short but has a stevedore’s handshake. His improbably broad nose and wobbly smile give him a slightly cartoonish appearance, and he looks like he’d be a lot of fun except that he seems to be on his most serious behaviour. In hesitant English that is much better than he thinks it is, he patiently counters every reading of his work that I put forward. The series of pieces using felt-tip pens speaks a language of schoolkid gaffs, making a virtue of what ought to be embarrassing faux pas, I suggest. “Some of the objects I designed could have several levels of lecture,” he says, meaning “meaning”. “You can see one thing, I see other things.” Yes, when he was a kid he did leave the odd Bic biro in his pocket, only for it to blow – “Pukh!” – but these works are about generating random, uncontrollable patterns. What about his Tablecloth Tableshirt – a shirt-like tablecloth with a collar for a centrepiece? It seems to mock our caution in sitting down to a meal in a clean white shirt. Nope, it’s a play on the word “tableware”.

Like a latter day Dadaist, Brízio likes to allow the forces of chance into his process. To create Journey, a series of ceramic vases made in 2005, he loaded the still-wet clay forms into the back of a Land Rover and drove a predetermined route that left the vases all lopsided. Sometimes, the important thing seems to be to avoid the hand as the obvious tool of authorship. In Sound System, he recorded the sound waves made by him saying the words “lamp” and “jar” and used them as drawings for a lamp and jar that were then made out of sheet metal. “It’s a process of drawing,” he says. “Usually in starting a project we use a pencil to make sketches. In Sound System I use words. The object comes from your body.”

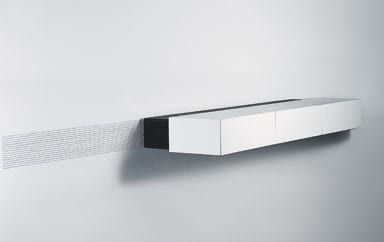

These are works about how the objects themselves are made as opposed to, say, how the user will interact with them. They are works about process. But there is another aspect to Brízio’s output, which is that it maintains an unusual dialogue with drawing and painting, or at least the act of mark-making. As well as the Giotto series (named not after the artist but the brand of pen he uses – “a happy coincidence”), his HB Shelf is fitted with pencils that look like they would mark the wall if you slid the shelf into position. Placing furniture can be a painful process, and this shelf suggests that you could leave a trace of that decision-making. But the interesting thing is that where most designers move from the two dimensions of the sketch to the three dimensions of the object, Brízio often keeps the two-dimensional explicit inthe works, if only through the drawing implements themselves.

This is most obvious in the stool he made for Galerie Kreo last year, which looks like a trompe-l’oeil drawing. The feet have flat extensions that create the illusion that the legs are kinked. The inspiration was a scene from Buster Keaton’s movie The High Sign, in which the hero draws a hook on the wall with a paintbrush and then puts his hat on it. Like a cartoon, I suggest. “Yes, but it was in 1920, and Buster Keaton made a rapid prototype in front of you. And when I saw that I was ‘Wow!’ And I started to think about this idea of the relation between design and drawing and the relationship between drawing and people. And I started to write several texts about the idea that we live in a drawing.”

The most striking thing about that sentence is that Brízio writes – not a discipline that most designers incorporate into their process. Does he enjoy it? “No, I don’t like writing, it’s not my medium. But I like to think, and when we write, the process of choosing words helps us to think.” The idea of living in a drawing conjures a world in which anything is possible, a world of suprises, where cabinets can open like windows onto the outside world or where a duster left on a sideboard can move magically when you open the door. The latter piece – Presence (2005) – is a Harpo Marx trick if ever there was one. And there is a sense that Brízio sometimes errs on the side of the gimmick, or the one-liner. He admits that this strategy – fostered by the Dutch scene of the late Nineties and picked up by many a young Brit more recently – has become “tired” and that he is leaving it behind.

It feels like the 39-year-old has not quite hit his stride. But then, circumstances have not always cleared the path for him. First there was the fact that he was a father at 20, and had to work (“anything”) to support his daughter. Then there were inconveniences like military service, and the fact that after two weeks at the Royal College of Art in London he had to withdraw to take care of his suddenly sick mother. And then, Portugal was not the most fertile of seedbeds. “Ten years ago in Portugal we didn’t have nothing about design – nothing,” he says. His teachers were sculptors and architects who were fixated on function. “They only talked about technical problems – it works or it does not work. I think design is related with people and not with machines; they only talk about machines.”

Things have improved in Portugal but he still sees precious few opportunities for designers in terms of commissions, especially if, like him, your ideas are not the most commercial. “Most of us don’t have the opportunity to work only as a designer,” he says. Yet he is one of the lucky ones, with a decent teaching post at the art and design college of Caldas da Rainha and something of an international reputation. “I love teaching,” he says, “but sometimes I have lots of problems because I can’t leave the teaching job.” He admits that he has considered moving abroad but it’s hard to imagine that he will – he doesn’t have the jet-set ambition of a Jaime Hayon. If anything, Brízio’s career has a southern languor that suits lovely but far from full-throttle Lisbon.

Like Harpo and Buster Keaton, the quiet Brízio can make something out of nothing. He has the imagination to turn a stain into a design or to see the graphic potential of invisible forces, like the human voice. At their best, Brízio’s works have something to say about people – about our haplessness or indecision or simply the way our perception can be a creative tool. Refreshingly, he has no interest in perfect forms. “I don’t make silent objects, objects that don’t talk about you, objects that don’t make you think.”

Painting a Fresco with Giotto #1, 2005, a faïence bowl with felt-tip pens

Painting a Fresco with Giotto #3, 2005, a faïence vase with felt-tip pens

Restarted dress with felt-tip pens, 2005

Window installation, 2005, at Lisbon’s City Museum

Tablecloth Tableshirt, 2000

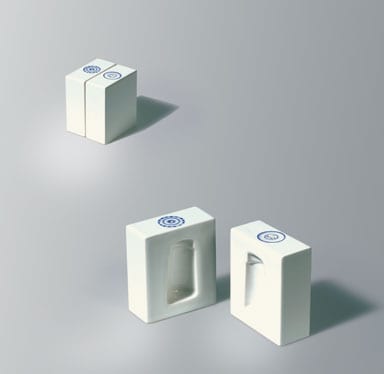

Pepper and Salt Shakers, 2005, produced by Cor Unum

HB Drawing Shelf, 2005, made of pencils and wood

Journey ceramics, 2005

Buster Keaton in The High Sign, 1921, provided inspiration for the Alice stool

Alice, 2007, a trompe l’oeil stool made of wood and stainless steel. A limited edition produced by Galerie Kreo

Sound System, 2003, a stainless steel jar inspired by the image of a soundwave