One of India’s most outstanding collections of South Asian art has been revealed with the recent opening of MAP Museum of Art & Photography, housed in a state-of-the-art building in South India’s capital city, Bangalore

Photography by Krishna Tangiral

Photography by Krishna Tangiral

Words by Jay Merrick

Superstar, if not super-banal architects often announce their new buildings in rancid surfs of hyperbole. Even OMA, with its halo of brusque radicalism, had no problem proclaiming their Taipei Performing Arts Centre with words and phrases such as ‘epicentre’, ‘spectacular landmark’, ‘monumental’ and ‘pulsating’.

In Bangalore, the newly opened Museum of Art and Photography (MAP) is an antidote to this kind of vacuous architectural fist-pumping. Designed by the Bangalore-based practice Mathew & Ghosh Architects, the building is emphatically not monumental, spectacular or pulsating.

But the independently funded MAP and its core collection of 7,000 east Asian artworks is instantly unique in a country where the government’s financial support for museums and museum-going is only slightly more than the $351m annual operating cost of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Photography by Iwan Baan

Photography by Iwan Baan

The MAP project was created and core-funded by Abhishek Poddar, the billionaire industrialist who has amassed tens of thousands of pieces of premodern, modern and contemporary art, textiles, crafts, Bollywood advertising and exceptionally important caches of historic photography. It’s a personal obsession rather than an investment strategy.

The genetic code of MAP’s design originated in what Nisha Mathew and Soumitro Ghosh describe as the ‘rich climate of investigation’ at the Ahmedabad School of Architecture in the 1980s via its legendary founder, the Pritzker Prize laureate BV Doshi and outstanding mentors such as Kurula Varkey, Neelkanth Chhaya and Miki Desai. The 1989 essay by A.K. Ramanujan – Is There an Indian Way of Thinking? – was equally crucial to Mathew and Ghosh’s design approach.

MAP’s architecture brings Ramanujan’s question into sharp focus. Bangalore, population 12m, has become India’s very own tech-drenched Silicon Valley, increasingly pock-marked over the last 20 years with developer-friendly ‘international’ architecture. Two salutary examples: the Kingfisher Towers, topped with a faux 19th century bungalow; and the UB Tower, whose pinnacle is a painfully crude, Lego-like homage to the Art Deco spire of the Chrysler Building in New York.

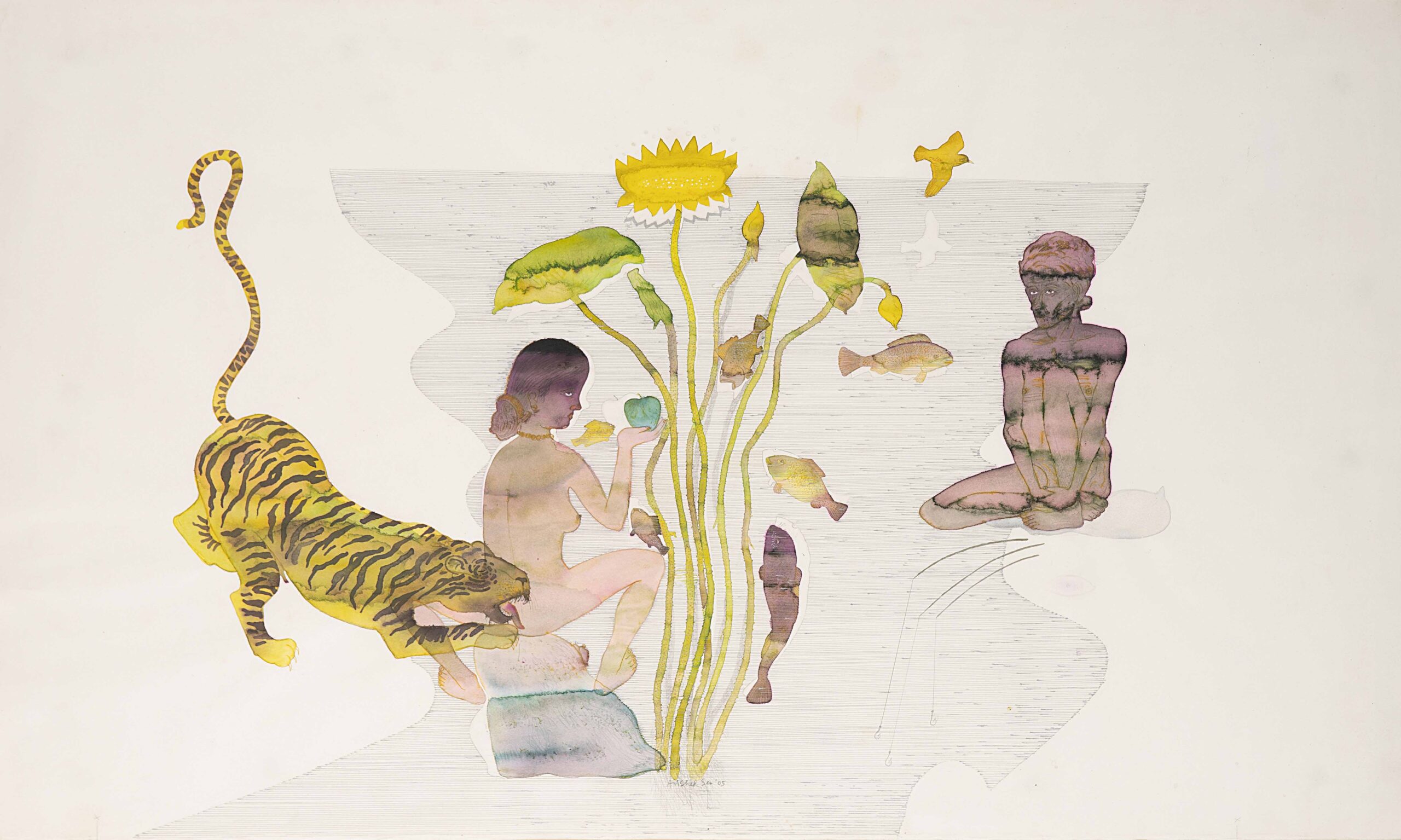

Image courtesy of MAP featuring Untitled (Virility), Avishek Sen. 2005. Watercolour on paper

Image courtesy of MAP featuring Untitled (Virility), Avishek Sen. 2005. Watercolour on paper

The inspirations and critical rigour experienced by Mathew and Ghosh at Ahmedabad 35 years ago are implicit in the design of MAP – not least Ramanujan’s belief that cultural expression is either context-free or, preferably, context-sensitive. MAP’s architecture is not only context-sensitive, but context-forming: this is the first Indian cultural building whose architecture and highly sophisticated digital engagement systems are designed to develop a new and much wider audience for art in a country where museum-going is typically perceived as an elitist, and therefore less than wholly democratic, activity.

Here, art history only surfaces at postgraduate level, and India has not even produced a complete encyclopaedia of its art. This makes MAP’s online Academy programme, led by Nathaniel Gaskell, hugely significant. He and his team are generating a global online database and teaching programmes for east Asian art. MAP is a ‘tanki’ for art – tanki being the local word for the mass-produced metal water tanks installed in Bangalore during the British colonial period.

The upper facades on three sides of the five-storey building are sheathed with stainless-steel panels almost exactly the same size as the historic tanki, and stamped with their original X-pattern. The bead-blasted panels have a soft, pearlescent gleam that radiate a calm material decorum which is simultaneously historic and absolutely modernist.

Photography by Iwan Baan

Photography by Iwan Baan

The hernias of exposed, metal-wrapped ducting on MAP’s east facade celebrate pure functionality. Thus, MAP’s external form is not an eye-con. Nor are the interiors, where structural elements and connections are nakedly exposed. This is not, in any of its details, pimped-up architecture – indeed, it is specifically ‘anti-spectacle,’ as Nisha Mathew puts it.

And so, considered purely as an architectural object, MAP is a fairly radical presence in Bangalore. The building’s main structure rises above a podium which creates a thoroughly public threshold which she describes as ‘a place of exchange, a place of equity and fragility’.

The five main galleries are on the upper floors, tied into a surrounding steel-trussed structure which delivers almost completely column-free gallery space. The centre of the west-facing facade is glazed, with a dichroic glass coating (Poddar’s idea) which coats the stairs and circulation decks with luscious splashes of constantly mutating colour.

Photography courtesy of MAP featuring Dahej (Lobby Still). Mumbai, Maharashtra. 1950. Silver gelatin print

Photography courtesy of MAP featuring Dahej (Lobby Still). Mumbai, Maharashtra. 1950. Silver gelatin print

The low gallery ceilings are clearly not ideal in terms of exhibition design, and they are the result of cramming an extra storey into a specified maximum building height. But this allowed the architects to fit in an auditorium, shop, research library, conservation department, an education centre in the basement, and a rooftop restaurant overlooking Cubbon Park, a delightful relic of Bangalore’s colonial Garden City period.

Can MAP transform art experiences in Bangalore, and further afield? Can it embody Soumitro Ghosh’s remark belief that ‘art creates new takes on society, and society has to evolve?’ Museum director Kamini Sawhney, Arnika Ahldag’s curation team, and Nathaniel Gaskell’s scholarly posse have clearly made an innovative start.

This third millennium tanki may not carry water, but the building is already a fertile oasis of physical art, and art via AI technology, holograms, QR code links and interactive projections and surfaces. MAP is the antithesis of a silo. Is there an Indian way of thinking?

The accomplished and implicitly ethical architecture of MAP confirms that there is, even as the art issuing from the building recalls the tensions of two slippery questions from T.S. Eliot’s poem, The Rock: Where is the wisdom we have lost in knowledge? Where is the knowledge we have lost in information?

Get a curated collection of design and architecture news in your inbox by signing up to our ICON Weekly newsletter