|

The recipient of this year’s Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement at the Venice Biennale discusses her career, Mies and the state of contemporary architecture. For the chance to win a copy of her book, Building Seagram, scroll down to the bottom of this article Phyllis Lambert, 87, is the recipient of this year’s Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement at the Venice Biennale. “Architects make architecture; Phyllis Lambert made architects,” Rem Koolhaas said of his decision to award the founding director of the Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA) the prize. Christopher Turner spoke to her about her influential life in architecture. Congratulations on your Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement. How did you learn that you’d been awarded the honour? Thank you very much. I got a phone call from the curator, Rem Koolhaas, telling me and I had to wait for weeks as it went before the board, unable to tell anybody – then I got an official letter. Isn’t it wonderful?

The Seagram building under construction in 1957 In his citation, Koolhaas called the Seagram building, “one of the few realisations in the 20th century of perfection on earth”. Your father originally commissioned a building by Charles Luckman that you thought a disaster. You spent months travelling around the US meeting all the great modernists in the search for an alternative, which you describe in your book, Building Seagram (Yale, 2013), as a crash course in architecture. What was it about Mies that so appealed? It was just two months, actually, in 1954. It was a great experience, of course. Together with Eero Saarinen and Philip Johnson, we made a list of all the architects to visit. Then I went and visited them in their offices. I was always intrigued by Le Corbusier, but what was so interesting was that all the younger architects defined their work as similar or different to Mies. And Mies had only done 860 Lake Shore Drive – he was in the process of doing this other building type at Crown Hall – you know the long-span thing – but that was it in America. He already had a major reputation in Europe, of course. But when I saw 860 Lake Shore Drive… You get a physical reaction from it, it’s so wonderful, it’s strict and so beautifully proportioned in the way the buildings work together, because it’s two buildings set at 90 degrees to each other, joined by a podium. It was unlike anything I’d seen.

The Seagram building, in New York, today As director of planning at Seagram, you set yourself up in a glass office next to that occupied by Mies and Philip Johnson, his collaborator on the tower, and you were keen to get involved as much as possible. Did they always welcome that? I had to fight my way in to be director of planning. I had my office with the architects – we had little cubicles next to each other, and it was an extraordinary experience, as you can imagine. I was a client. My father was the client du jour, but I was the client in practice. Philip Johnson said something funny – he said: “She doesn’t know anything about architecture, much, but because she was there, there was no hanky-panky.” I was in all the meetings with the people in real estate, the engineers, the associate architects, and I interacted with the company and particularly with the contractor. I was there to ensure that there were no secret deals, that no one played any games.

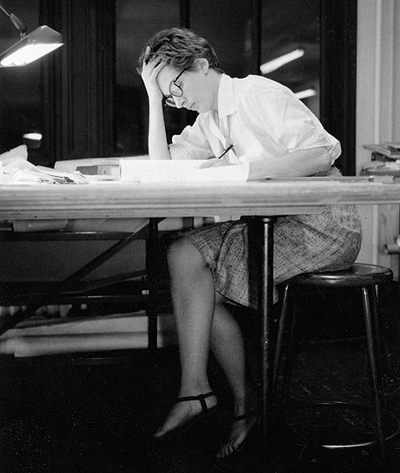

Phyllis Lambert, 1959, during her studies at the Illinois Institute of Technology (image: Ed Duckett) You later went to the Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT) and apprenticed at Mies’s Chicago firm. I first went to Yale and after two years at Yale I transferred to IIT. Mies was no longer teaching there, but I’d seen the kind of work they were doing and those were the things I wanted to learn. I wanted to learn the practical things, such as how to use a 2 x 4. I wasn’t interested in speculation. There was a kind of honesty about the work at IIT. I certainly learned how to put a building together, and I learned that on the job too, at the Seagram Building. It was just a magnificent experience. I didn’t apprentice with Mies. One summer I made up some credits by working at his office. I was his student, there to learn. Not that it diminishes his buildings, but a new edition of the biography of Mies by Franz Schulze (co-written with architect Edward Windhorst) suggests Mies was something of an alcoholic. Was that your experience? That’s ridiculous. Mies drank a lot, but he was certainly not an alcoholic. So what if he was. There was no evidence of it at all. Some people drink a lot and are OK, some people aren’t. Mies drank a lot, he liked to drink. I never saw him lose any control, and I saw him a lot. In New York he’d come over to my apartment and he’d drink – a few martinis and whiskeys – and say, let’s see the blaue Stunde, the dawn come up. But that doesn’t make you an alcoholic. That kind of gossip has nothing to do with the world, the spirit, the importance of architecture. You designed the Saidye Bronfman Centre in Montreal in the Miesian mould. What else did you build? I decided I wanted to do a building that was very Miesian. I had a good schooling. I knew how to put things together and it was a fine experience. My next project was working with Gene Summers, who was from Mies’s office, and we did the restoration of the Biltmore Hotel in Los Angeles. Then I went back to Montreal and was very much involved in the stopping of the demolition of the 18th and 19th century fabric of the city – walking in the streets to stop things, a sort of urban guerrilla. So I was working on architecture in many ways. But I did a little theatre for my mother, a film theatre for their house. I renovated my own 1860s home and two other little houses in one of the streets in a popular area of Montreal – little things like that.

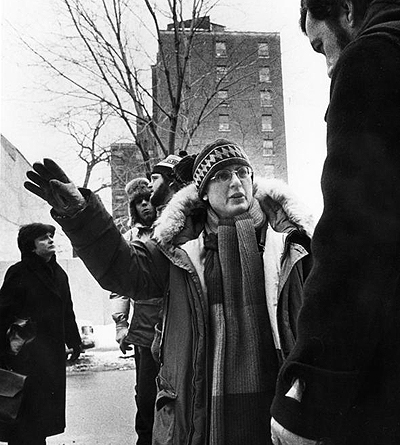

Phyllis Lambert, 1981 at the heart of the battle for the development of Milton-Parc neighborhood, Montreal You set up the CCA in 1979. Was its modernist mission – to emphasise the importance of architecture in helping create a better society – counter to the postmodernist mood of the time? I found that cities in North America were trying to look like bombed out cities in Europe and the tremendous demolition of this historical fabric was being done by people who didn’t know anything about architecture. I was fascinated by the subject. I’d started forming a collection of architectural drawings when I was working in Mies’s office out of curiosity. It’s very hard to read architecture drawings; you have to learn, like any other kind of language. And I was interested in how people had done this in the past, in different places and at different times. I also started a collection of photographs and, of course, books. I was appalled by much of what the postmodernists did, the stupid things they did, but there were some very good attitudes, because the modernists eschewed what was around a building. They thought we just had to knock everything down, and I didn’t believe that. Postmodernists were interested in context. You’re a great collector, with a sizeable archive of Mies-related things. What are the CCA’s other jewels? We have some key work by Mies, but the major archive is at MoMA. We have a fantastic collection of prints and drawings from the 16th and 17th centuries. We have a major collection of architectural photographs, and I think we sort of created the idea of that as a subject. We have an important collection of Le Corbusier and some Wright. But what we really have is strong and complete archives of Cedric Price, James Stirling, Aldo Rossi – architects at the leading edge, who were pushing the boundaries. CCA is developing into the great archive of 20th century architecture. In his essay for the Mies in America show, titled Miestakes, Koolhaas said, “I do not respect Mies, I love Mies.” How do you judge his self-described “Miesian interference” on the IIT campus [the McCormick Tribune Campus Centre, which faces Mies’s Crown Hall] I think it’s a brilliant project. That’s a very difficult thing to do on a campus by an architect of such consistency. The campus is extraordinary because you can see the development of Mies’s thinking with each of the building, yet it’s a very coherent body of materials. I was on the jury that chose Rem’s project for the student union and I think it’s a brilliant building. Rem has this very strong edgy part, which makes him so great. He pushes hard against what’s there. The spatial qualities of that building are extraordinary. As you step down as chair of the CCA, in what state do you leave architecture? Stepping down as chair has nothing to do with leaving architecture. I think architecture is at an extraordinary moment. I love the very question that Rem has asked in the Biennale, the idea of Fundamentals. It’s not dealing with architects – most recent Biennales have dealt with star architects and Rem has objected a lot to some of the crazy types of forms that people are looking for. It’s time to get back to the essentials. The world is changing at such a fast rate now and cities are changing at a geometric scale – we have to deal with that. There are good architects and there are great architects (and there are commercial architects – I don’t mean those), and they know how to think, they question all the time and know how to approach, analyse and deal with the issues at hand. They know what society is and what we have to do. To win a copy of Phyllis Lambert’s book, Building Seagram, published by Yale University Press, send your answer to the question below to [email protected] A winner will be selected at random next week from all the entries. Which architect was photographed in 1986 scrubbing the floor of the reconstruction of Mies’s Barcelona Pavilion?

|

Interview Christopher Turner |

|

|