|

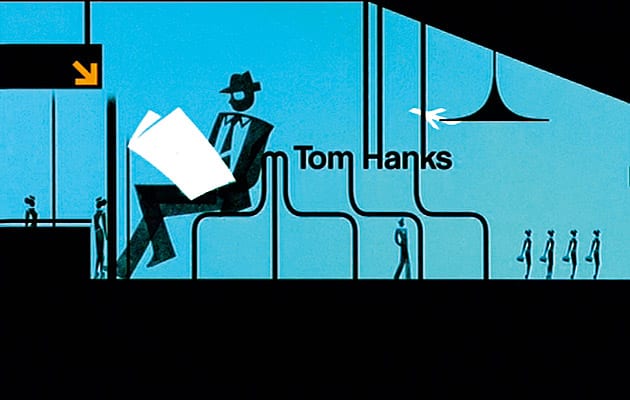

Still from Catch Me If You Can (image: Olivier Kuntzel and Florence Deygas) |

||

|

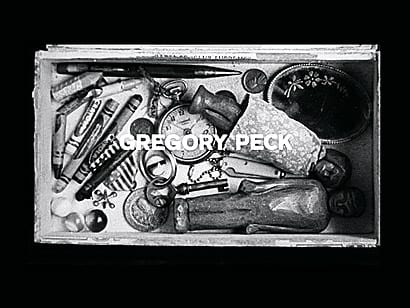

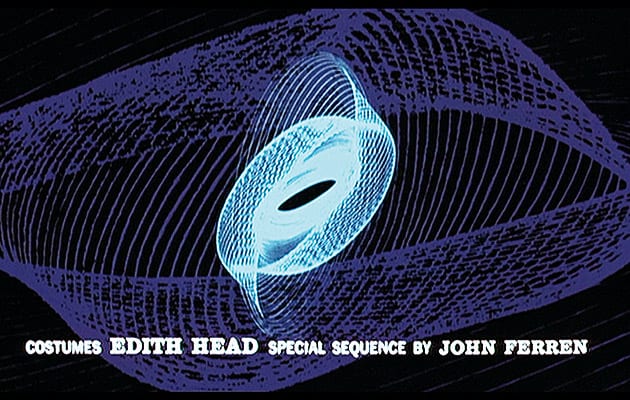

Little works of art within a film, the opening credits can combine utility and beauty. Francesca Gavin admired the best in a darkened room. Remember the first time you went to the cinema? Images flickering on a screen in a darkened room, drawing you into a story outside your experience. Those opening credits are not just gift-wrapping. They are arguably some of the most important seconds of a film. The graphic images, typography and edited images are miniature works in their own right, ones that reinforce and push the meaning of a feature. Their importance is definitely clear after seeing Vorspannkino: 54 Titles of an Exhibition at the KW Institute for Contemporary Art in Berlin. This show brings together title sequences by Maurice Binder, Kyle Cooper and Elaine and Saul Bass, alongside work from Teruo Ishii, Alejandro Jodorowsky and Jean Cocteau. It’s a strange feeling watching so many beginnings, yet there isn’t the expected sense of frustration at not seeing the narratives pan out. Instead, the titles create a sense of anticipation. It almost feels romantic. The ground-floor cavernous space is set up like the back of row of a cinema, a few rows of seats separated from the screen by metres of black space. On the other three floors titles pop up on different walls or hanging screens so the viewers move between them in little groups. There are mainstream blockbusters, Bond movies, comedies, sci-fi, dark thrillers and horror films to see. The balletic ring opera of Raging Bull (1980) and the hilarious trash of Attack of the Killer Tomatoes (1978). The graphic innovation of Stan Brakhage alongside Maurice Binder’s graphic animation for Charade (1963). Kyle Cooper’s discordant titles to Se7en (1995) and Mimic (1997) and the kitsch pastiche of Tarantino’s Death Proof (2007). There are also some delightful rare choices in the show, such as Pier Paolo Pasolini’s hilarious Uccellacci e Uccellini (1966), where the titles are all sung in comic style. Some of the most interesting sequences are the ones that deconstruct film itself, forcing the viewer to become aware of the mechanisms behind the screen. In The Magnificent Ambersons (1942), Orson Welles narrates the titles while showing the behind-the-scenes cast and crew off and on duty. He intentionally rips away any sense of fantasy in film and still teases us to cross the boundary between fiction and reality. Jean-Luc Godard’s Le Mépris (1963) is, not surprisingly, much less whimsical. We are on an Italian film set watching a camera tracking an actress as she walks towards the screen, while a voiceover narrates the titles. Just as the camera reaches the screen itself it pans and faces the audience, and we fall under the gaze of its dark black hole. A disturbing and surprising twist. Among the acres of creative work, Saul Bass still shines out as the master of the title. The variety of his work is awesome, as is the innovation in his graphic approach. From the paper-ripping opener of Bunny Lake is Missing (1965) to the features twisted in warped mirrors in Seconds (1966), Bass has an unsurpassed hold on a viewer’s emotion. He makes the familiar unfamiliar, and reveals beauty in the simplest things. Looking at film titles over a century, what is interesting is that they are persistently experimental rather than proceeding through a linear evolution. You come away fascinated at the breadth of relationship between text and image – how complex narratives can be created by this simple juxtaposition. It is this relationship that has had an influence far beyond cinema, but on graphic design as a whole.

Still from To Kill a Mockingbird (image: Stephen Frankfurt) |

Words Francesca Gavin |

|

|

||

|

Still from Vertigo (image: Saul Bass) Vorspannkino: 54 Titles of an Exhibition is at KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin, until 19 April |

||