|

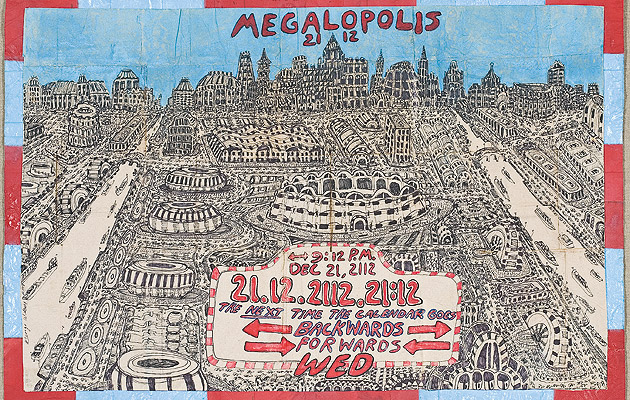

George Widener’s futuristic Megalopolis (image: Megalopolis 21. 2005, George Widener, Courtesy of the Hayward Gallery, London) |

||

|

The painstaking, at times obsessive, work of self-taught artists and inventors presents a poignant vision of the future says Will Wiles Even the most gaudy pomo confections look staid compared with the architectural work of Bodys Isek Kingelez. Self taught and unbuilt, Kingelez has completed models of dozens of buildings to be slotted into a thorough redevelopment of his home city, Kinshasa, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. His UN building gives world government a fairground aesthetic by way of The Nutcracker. The Bodystand tower lifts off the ground at a priapic 45-degree angle. The Palais d’Hirochime is a fantastic exercise in Fisher Price orientalism. Kingelez’s models are among the first things the visitor sees on entering The Alternative Guide to the Universe at London’s Hayward Gallery, and they whet the appetite marvellously. The Hayward, working with “outsider” art specialist the Museum of Everything, has brought together a fascinating collection of autodidacts, untrained inventors, rogue scientists and maverick artists, each with an oblique, comprehensive and elaborate view of reality. Many of these visions are, like Kingelez’s, architectural. Take AG Rizzoli, who as a 19 year old was so overcome by the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco that he dedicated his life to designing a similar showcase on a wildly larger scale. The result, YTTE (Yield To Total Elation), is an expansive habitat for beaux-arts charismatic megafauna rendered with draughtsmanship that commands the eye and the imagination. The key to buildings, while not exactly helpful, is pure poetry: Tillers Telling Temple, the Vitavoile of Happiness, Spiggot Brightspot. Marcel Storr’s buildings and city plan are less meticulous – their lurches of perspective give them a vertiginous quality – but they are no less fabulous. Spindly cathedrals perforate the sky with more needles than a brimming sharps bin; the megastructural fantasies of Sant’Elia mate with the over-decoration of Gaudí in opiate Angkor metropolises. A street sweeper, Storr worked in secret at night on pencil drawings so dense the paper shines like lacquer. Yearning permeates many of the artists’ architectural work. Given Kinshasa’s past half century, one can readily understand Kingelez’s eagerness to make his “Kinshasa of the Third Millennium” a “free, peaceful city”. William Scott’s plan to replace San Francisco with “Praise Frisco”, a charismatic Californian Jerusalem filled with “praise dancing”, “Gospel fests” and “wholesome encounters” is plainly rooted in kindly exasperation with the version we have. The “calendar savant” George Widener, who sifted the weeks and months of the far future for pattern and meaning, designed his own ideal cities based on those calculations. “I believe a good working city would be one with balance, where everything is in its proper place,” he states. “Cities are often big, dirty and chaotic places, things break down … Calendars are balanced out, they repeat and mirror each other … I think my cities are very correct.” It’s hard not to feel sympathy for a mind so let down by the inexactitude of the world, and so concerned to set it right. Vehicles evenly fill the roads of Widener’s Megalopolis 2053, and boats its geometric rivers. Even its grandest statement qualifies itself to eliminate possible error: “All Are Welcome Here in the Future Years (Probably).” In fact, yearning could be the sensation common to everything in the Alternative Guide, from the amateur masterplanning to the one-man cosmologies and secret languages. There’s horror vacui, for sure. But there is also a pressing sense of wanting to be understood, of wanting others to experience the revelation the artist has undergone. Paul Laffoley’s giant canvases detailing the philosophy gifted him by an alien visitor and explaining the power of thanatonic energy are heartbreaking in their organisation – if the lines and lettering are sufficiently neat, then surely the viewer’s mind will be won? Or perhaps Melvin Way, who covered scraps of paper with arcane chemical symbols and equations, did not want to be understood, but to understand. Everything the Hayward has gathered taps straight into the mains energy of the human experience. Even when it’s babbling beyond comprehension it will impress and move. (Probably.) |

Words Will Wiles |

|

|

||

|

George Widener’s futuristic Megalopolis (image: Megalopolis 33, 2005, George Widener, Courtesy of the Hayward Gallery, London) The Alternative Guide to the Universe, Hayward Gallery, London, Until 26 August |

||