|

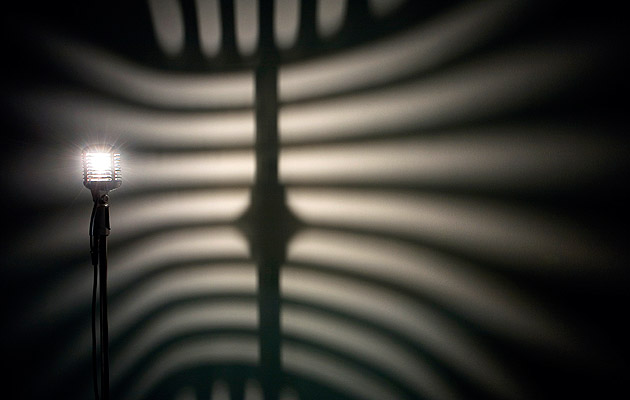

Triplight by Camille Normeant, 2008 (image: Courtesy the artist and Gasser Grunert Gallery) |

||

|

Sukhdev Sandhu welcomes MoMA’s first exhibition of sound art, but finds that the genre rings hollow when stripped of context Sound art, the musician Alan Licht wrote at the close of his 2007 book on the topic, operates between categories: “It’s not emotional nor is it necessarily intellectual.” That in-betweenness hasn’t stopped it from spawning a small library of monographs over the last decade, or being commissioned by public arts organisations, or even – as with Susan Philipsz’s 2010 Turner Prize victory – winning major awards. After all, in-betweenness is very fashionable: academics and curators are wedded to anything they can label as ambivalent, intersectional, cross disciplinary. It’s surprising then that MoMA’s current sound art show, Soundings: A Contemporary Score, is the first that the New York institution has ever organised. Sixteen works are presented, few of them having much in common with each other. The right wall of the corridor leading to the main area of the gallery features Tristan Perich’s Microtonal Wall (2011), a 25ft-long panel punctured by 1,500 one-bit speakers, each tuned to its own microtonal frequency. Listened to – or rather heard – from a distance, it’s a sea of white noise, an orchestra of vacuum cleaners. Will people have the time or the patience to stand before individual speakers and attend to their pointillist sonics? Is it important to do so? Most visitors tend to walk quickly across the panel: the effect – a slightly euphoric, slightly cheesy whoooosh – is close to the “soar” that Dan Barrow, writing in The Quietus, has identified as a signature feature of modern pop music. “Sound is materially invisible but very visceral and emotive,” reads Susan Philipsz’s text about her work. “It can define a space at the same time as it triggers a memory.” That claim is contradicted by her own piece: it takes Pavel Haas’s 1943 Study for Strings, written and performed in the Theresienstadt concentration camp shortly before the composer and most of the players were killed, and focuses on its viola and cello parts which are played in a semi-dark across eight speakers. Stripped of its backstory, the work defines and triggers nothing. Even with that backstory, Philipsz’s work comes across as affective tourism, cultural appropriation. Another dark history is explored by Jacob Kirkegaard in Aion (2006). Apparently influenced by Alvin Lucier’s landmark I Am Sitting In A Room, he travelled to Chernobyl to make recordings of four abandoned spaces near the nuclear plant: a church, a gym, a concert hall, a swimming pool. These he played back into the spaces themselves. Sometimes they sound like leaves or embers. Sometimes they sound like the low-key soundtrack to a cult horror movie from the 1970s. But as with its visual documentation – the derelict buildings could easily be from Manila, Mexico City or Preston – the acoustic force of Kirkegaard’s piece relies heavily on contextual captioning. Some of the most effective works in the show are by lesser known artists. All.Day. (2012) is a witty, slur-like graphic representation by Christine Sun Kim, who was born deaf, of the expansive path her hand would have to take to communicate the concept “all day” in American Sign Language. In Before Me (2012), Richard Garet upturns an LP platter and has a microphone pick up not only the resulting surface noise but the sporadic thuds of a marble that moves fractionally across the platter before being overwhelmed by the momentum of its spinning; it’s not the attention to surface noise (that’s a staid sound-art trope these days), so much as the way it dramatises the difficulty of producing LP noise that is poignant at a time when digital music is created and circulated almost effortlessly. Soundings is a good chance for newcomers to sound art to sample important figures such as Carsten Nicolai and Florian Hecker. But it needs more of a conceptual underpinning. Most of all, it needs more space: too many pieces are marred by sounds leaking from other rooms, as well as the surface noise that afflicts all galleries – the mobile-phone chatter of visitors. Soundings: A Contemporary Score, MoMA, New York, Until 3 November |

Words Sukhdev Sandhu |

|

|

||