|

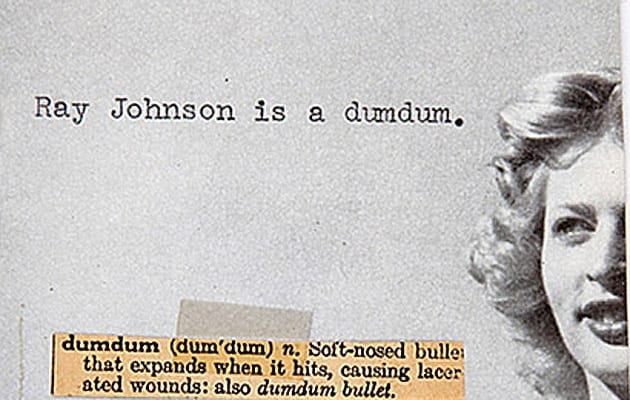

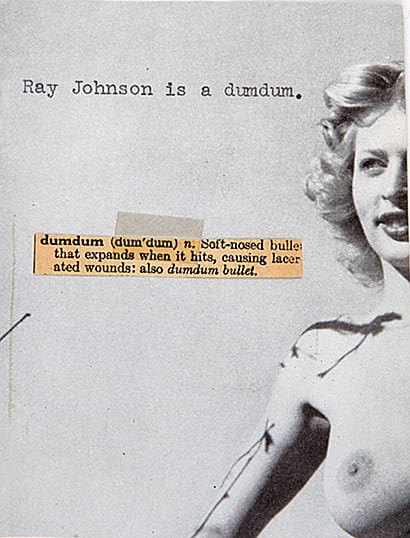

Untitled (Ray Johnson is a Dumdum, 1963 (image: William S Wilson Collection) |

||

|

The mail art of Ray Johnson is a brilliant private form of self expression that reveals everything and nothing, writes Giovanna Dunmall. “I’m a collagist, not a painter,” Ray Johnson says in How to Draw a Bunny, a documentary about his life. This is probably the clearest thing he says about himself in the film. His friends, colleagues and peers don’t fare much better. Even sculptor Richard Lippold, his lover for 27 years, says he knew very little about the man he was intimate with. In life, Johnson appears to have been eccentric and unknowable, in death he has become an even greater enigma. The collages, postcards, letters and ink drawings now on show in the not-for-profit Raven Row art centre in London, are expressive, layered and important, and at the same time vacuous, inconsequential and absurd. Johnson once rented a helicopter so he could throw 18m-long hot dogs over Rikers Island in New York as part of an avant-garde festival. He was surprised when people below ate them. His dealer Richard Feigen thought the artist was “on another planet”, saying he would talk and talk but reveal nothing of himself. He also thought Johnson was one “of the most interesting artists of the 20th century”. In his collages Johnson brought together images (both created and found, a preoccupation of the Bauhaus movement he was inspired by) of pop-culture icons, such as Elvis or James Dean, art world celebrities and his friends. He started sending them to curators, collectors, friends and colleagues in the 1950s. As he retreated from the art world to his house in Long Island in the early 1970s, his so-called correspondence art became his main form of interaction with the public. Keeping the collages to himself, he posted hundreds of reworked and overlaid photocopies of them. His ink drawings and images were, in his own words, “chopped up, shuffled and condensed”, old work was recycled into new tile-size pieces, and the whole made to fit into an envelope. In one piece in the exhibition there is a key, a drawn key surrounded by a frame, James Stewart’s birth date, a pen-and-ink version of Picasso’s Minotaur, a rusty hook and a date alongside the name Evelyn Keyes. I am certain the work is a commentary on the hypocrisy of marriage (he and Lippold were together, while the latter was married) and how it signals the demise of love and creativity. But then I see that the collage has five dates on it: 1968, 1988, 1989, 1992 and 1994, and I am no longer sure of anything. Johnson has obviously reworked the piece, adding and subtracting words and images, and with each new layer all prior incarnations are erased or defaced. More than the content, it is the composition and production that now fascinates. If Johnson were still alive today (he died mysteriously out at sea in 1995) it would be as open to alteration as before. His was a peculiarly private form of exhibitionism and self-promotion, an endless performance that could be titled in the same way as one of Johnson’s drawings on display at Raven Row. It bears the words “Ray Johnson’s History of Ray Johnson” in an archaic script. Devoid of all the usual paraphernalia, the piece hints at the possibility of autobiography and narrative, but then there is none. Or rather, there is plenty. The works are part-figurative, part-abstract and part-riddle, and are only ever partly comprehensible, but they are always and exclusively about Ray Johnson.

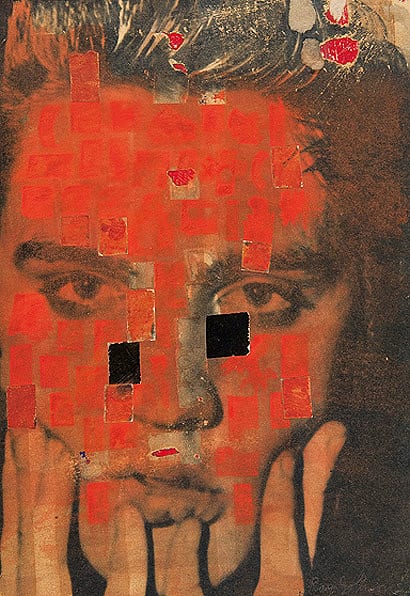

Elvis 2, 1956-7 (image: William S Wilson Collection)

Untitled (Ray Johnson is a Dumdum, 1963 (image: William S Wilson Collection) Ray Johnson: Please Add to & Return is at Raven Row, London, until 10 May |

Words Giovanna Dunmall |

|

|

||