|

|

||

|

The personal is political in an exhibition that presents works by mid-century female designers and artists, alongside those of their contemporary counterparts, says Laura McLean-Ferris Split over two floors of the Museum of Arts and Design, Pathmakers is an almost all-female exhibition that presents mid-century modern work alongside that by contemporary designers and artists – the title refers to the space women artists and designers carved out for themselves, on finding certain routes blocked to them. Embracing one of America’s most fetishised design periods, the exhibition looks closely at the richly textured works of artists such as Dorothy Liebes, whose room divider for the United Nations Delegates’ Dining Room (ca. 1952) is a luxuriantly rich woven mix of grainy, natural fabrics in oatmeal shades, striped with glamorous bands of azure and a plastic-covered lurex that provides a metallic copper finish.

Re-Lounge Chair, ca. 2013, by Hella Jongerius for Galerie Kreo In the mid-century section, abstraction is the focus, and the effect is such that second-wave feminism (Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex was published in English in America in 1953, roughly the beginning of the timeline) manifests here as a kind of literal backdrop. Panels, curtains, wall hangings and room dividers make up a large part of the exhibition: on Sheila Hicks’s panels, made for the auditorium and boardroom of the Ford Foundation in 1967, geometrically precise lines of golden silk create thick circles on linen. Eva Ziesel’s joyous Belly Button Room Divider (1957) comprises double-ended vessels in cheerful coloured glazes that curve into a central “belly”, strung onto long rods to create undulating lines that intervene into a space with their physicality. It’s fair to say that the choreography of the exhibition is a little staid, and wall texts could have contextualised the mid-century work in a way that not only emphasised the makers’ lives and objects, but also their place within larger artistic movements and cultural changes. Helpfully, relationships between women are made clear: Agnes Martin, for example, enjoyed wearing Alice Kagawa Parrott’s woven jackets, and was also a friend of experimental freestyle weaver Lenore Tawney.

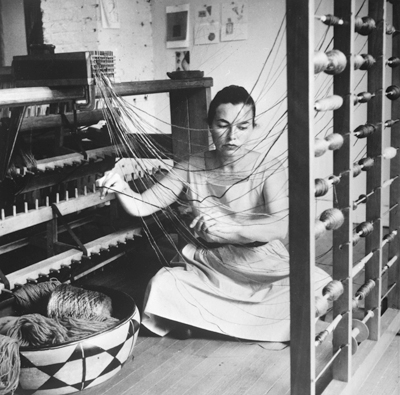

Lenore Tawney in her Coenties Slip studio, New York, 1958 In the contemporary section, the two strongest pieces are by artists, rather than those who chiefly work in design, and there’s a mix between formal and political associations. Polly Apfelbaum’s installation of dozens of hanging blanket-sized silk rectangles, coloured in variations of dots using a punch card and felt tip pens, were based on a 1950s handweaving pattern book. They are painterly, but retain their domestic, nursery tone where the ink bleeds softly into the fabric. Michelle Grabner’s colorful experiments with paperweaving, Untitled, 2014, which echoes Anni Albers’s designs upstairs, began after her children brought home some paperweaving projects from school. Transgender artist Gabriel A Maher’s DE____SIGN (2014) are costumes and videoed performances that explore formal grids and geometries for their androgynous potential, while Hella Jongerius’s designs for the United Nations Delegates’ Lounge make deliberate features of mismatching buttons on sofas, and somewhat haphazard sizing. Jongerius’s designs are the very opposite of neat and corporate, and her designs are a reminder that the personal is political – especially in a political space.

Resilient Chair Frame, ca. 1948-1949, by Eva Zeisel |

Words Laura McLean-Ferris

Above: Still from DE___SIGN (video), 2014, by Gabriel A. Maher

Pathmakers: Women in art, |

|

|

||