|

|

||

|

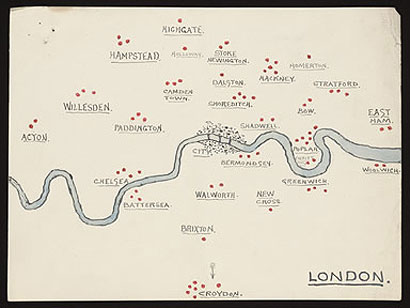

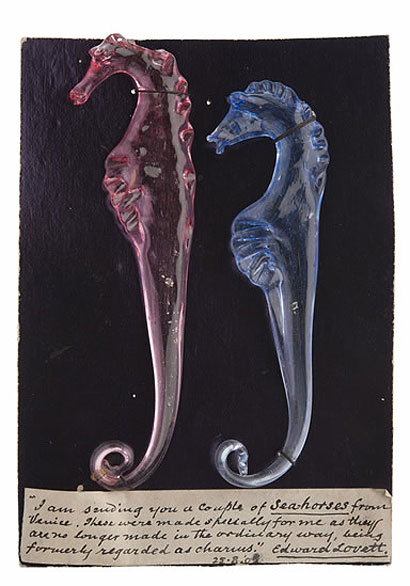

In 21st-century London, where cynicism is the new religion and fewer people than ever attend church regularly, it’s rather remarkable that the Wellcome Collection should stage an exhibition about faith, hope and chance. Even if we are less religious than our forefathers, we’re probably just as superstitious: celebrities sport red kabbalah bracelets, riders check their horoscopes daily and sportsmen have lucky socks. While today such trinkets seem ridiculous, the sheen of history makes them far more interesting. In Charmed Life, artist Felicity Powell has curated a selection of dozens of charms and lucky amulets once treasured by their anonymous owners, now museum artefacts. Don’t understand why you can’t have a baby? Carry a carved bone frog for luck with fertility. Among the other charms, the miniature sea horses and bone circles are powerful symbols of humanity’s constant attempt to find meaning and reason in messy Mother Nature. The amulets are part of a larger collection amassed by banker and obsessive folklorist Edward Lovett, a collection which he eventually sold to Wellcome and is today housed at the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford. Though it is not known to whom many of the objects belonged or were made by, this detracts not at all from their power. A collection of blue glass beads worn by those who believed they would keep bronchitis at bay are wonderful, tactile objects, but it is Lovell’s hand-drawn map of where one was able to buy the beads in London in the early 1900s that provides fascinating context for the widespread use of such amulets during this period in London’s history.

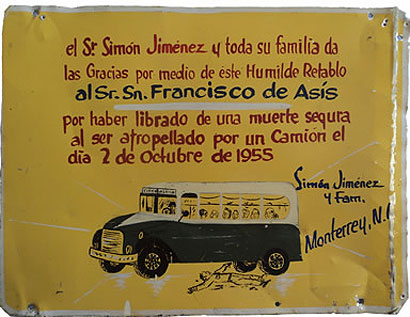

credit Wellcome Library The other part of the exhibition is Infinitas Gracias: Mexican miracle paintings, the first major display of Mexican votive paintings outside of Mexico. Alongside these votive paintings ¬– from the 18th century to the present day – there is also a display board of contemporary votive offerings: wedding dresses, baby shoes, photographs, endless hand-written notes and rosary beads. Though these offerings are interesting they have none of the charm of the votive paintings which are remarkably captivating. The votives are small paintings, often on roof tiles or boards. Each painting represents a moment of personal disaster or tragedy where the individual begs a saint for assistance. In return for this assistance, the supplicant promises the saint a dedicatory votive: each painting is the making good on a promise. It is not difficult to imagine these votive paintings assembled in a contemporary gallery as “outsider art”, yet what is remarkable about their appearance at the Wellcome Collection is that, despite the often extraordinary artistry and charm of their naive figurative style, the exhibition never allows you to forget that these pieces have a very specific functional purpose. Despite this function, the votives are beautiful, often humorous, objects that reward repeated viewing. There are many interesting parallels that come from viewing the exhibitions ¬– charms of the superstitious and votive paintings of the religious – side-by-side. Not least the scale of the objects. Despite their different purposes, these are all portable objects that help make the lofty worlds of faith, chance and superstition feel a little more human.

credit Santuario de San Francisco de Asis de la Diócesis de Matehuala / INAH

credit Wellcome Library

credit Museo Nacional de las Intervenciones

credit Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford Miracles and Charms is at the Wellcome Collection, London until 26 February 2012. |

Image Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford

Words Crystal Bennes |

|

|

||