|

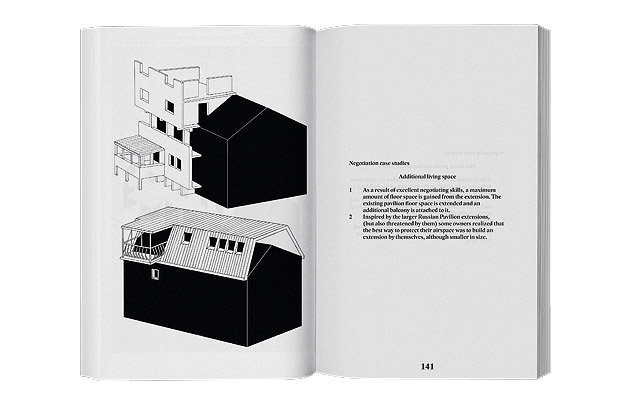

Makeshift extensions in a Belgrade suburb |

||

|

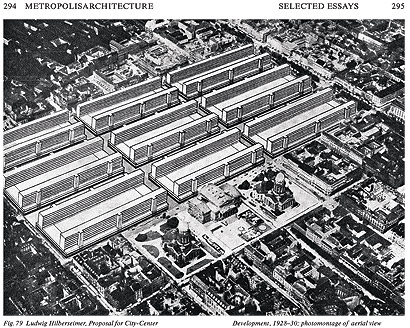

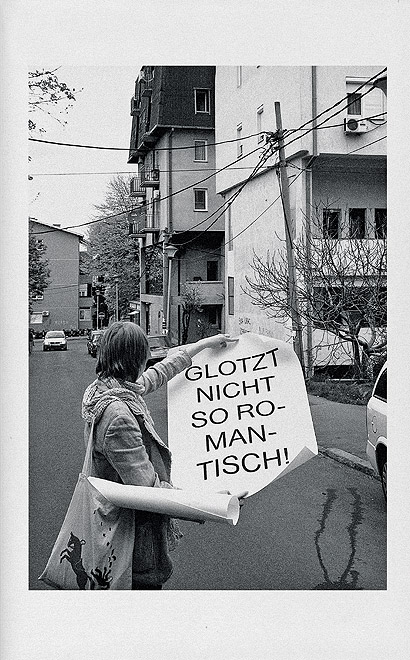

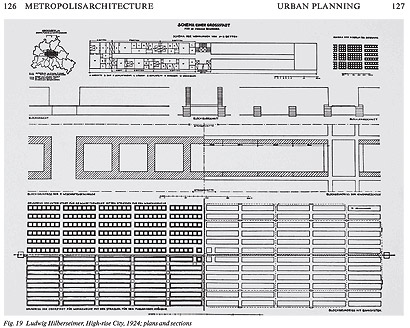

The first English translation of a classic of modernist planning and a recent work on informal structures shed new light on a polarised subject, says Owen Hatherley The current British planning minister, Nick Boles, once asked: “Do you believe that clever people sitting in a room can plan how people’s communities can develop?” For Boles, “Planning can’t work. Chaotic therefore in our vocabulary is a good thing.” Many, even those who consider themselves Boles’s political opponents, seem to agree. “Planning” means bureaucracy and authority; “chaos” an organic informality. Two pocket-sized books – one a notorious handbook of high modernist city-planning, the other a study of the effects of planning’s disintegration in one city – are about the extremes in this debate. In both, what initially seems simple becomes slippery: neither planning or chaos are entirely what they seem. The former is the first full translation of Ludwig Hilberseimer’s Metropolisarchitecture (1927), but even if you’ve never heard the name, you probably know its most famous images. They’re of a “project for a High Rise City”, and depict an immense, airy prospect, where identical slabs surmount a system of pedestrian walkways; underneath them is a motorway. What makes these images so enduring as emblems of planning-as-terror is Hilberseimer’s draughtsmanship, in a deliberately bland, anti-architectural style resembling the paintings of George Grosz. The people and cars are minuscule in comparison with the vast spaces around them. The buildings are deliberately empty and featureless, with an overwhelming repetition and scale. It’s an inadvertent prophecy of 1960s urbanism at its worst: the modernist planning that nobody will rehabilitate. A world rebuilt without accident, without streets, without beauty; a city that is “logical, unambiguous, mathematics, law”. The images in Dubravka Sekulic’s Glotzt Nicht so Romantisch! Hilberseimer’s book was always more looked at than read. The accompanying text makes clear that the point of the images is the irrelevance of aesthetics altogether. A committed socialist, Hilberseimer believed that affection for the historical city was merely sentimental; that the picturesque spaces left by previous eras’ refusal to plan actually made us unfree, binding city-dwellers to the caprices of property speculators. Urban priorities should be elsewhere – the obliteration of overcrowding, squalor, disease. The city might look boring as an object of contemplation, but the lives lived within it would be immeasurably better. Sekulic, meanwhile, depicts how the love of the picturesque still serves to efface exploitation. In the 1990s Yugoslav “self-management socialism” became emergency self-build to house war refugees. This gradually became self-cannibalisation, when two-storey houses were turned into seven-storey blocks without lifts, the new masonry structures built on to the original prefabricated structures. Cantilevers and mansard roofs with three storeys inside are all means of circumventing the already light regulation; the result, while both odd and unplanned, no longer feels like communities doing their own thing, but like a deeply ruthless and cynical manoeuvre; “every spatial decision was geared towards maximising the profit for the investor, and stretching the future legal terrain a bit further”. Since radical architects tend to be infatuated with the ad hoc networks and romantic appearances of informal urbanism, both books are a much-needed counterattack of facts, data and legal analysis, making precisely clear how a city emerges, who benefits from it and who profits. The unnerving images in both work as a challenge – we have the power to make cities work – but when that finally occurs, will you be able to stare at them romantically any more?

Hilberseimer’s 1928-30 proposal for a city centre

Brecht’s slogan: translates as “Don’t stare so romantically!”

The first full English translation of Hilberseimer |

Words Owen Hatherley |

|

|

||

|

Metropolisarchitecture by Ludwig Hilberseimer, GSAAP books, $19.95 Glotzt Nicht so Romantisch! by Dubravka Sekulic, Jan van Eyck Academy, €13.00 |

||