|

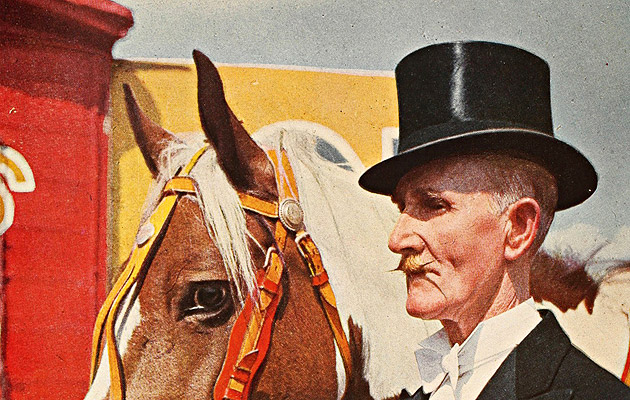

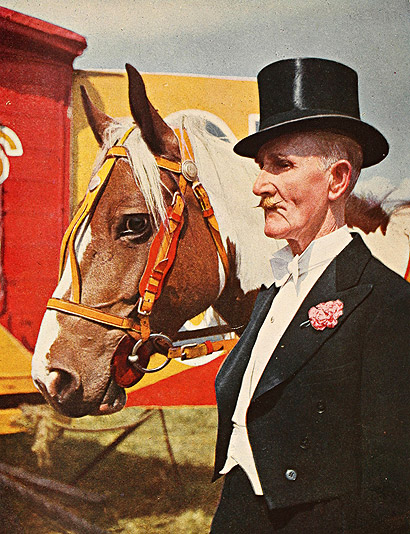

From British Circus Life, by John Hinde, 1948 (image: National Media Museum) |

||

|

The organisation’s visual archive raises intriguing questions about the line between social study and snooping, says Isabel Stevens With its network of spies, each assigned a number and ordered to record the activities of friends and strangers with their hidden notebooks and cameras, Mass Observation could be an Orwellian nightmare, a surveillance society like those established by the Nazis, Stalin or the Stasi. Except of course, this prying organisation was set up in 1937, not by the fascists that were taking over Europe at that time, but by a poet (Charles Madge), a filmmaker (Humphrey Jennings) and an anthropologist (Tom Harrisson). Their objectives were to recruit both artists and anonymous volunteer observers who, “like Courbet at his easel”, would record ordinary people’s lives. In the same year that opinion polls were introduced to Britain, the trio’s “weather-maps of public feeling” were distilled into books and newspaper reports and occupied a place somewhere between an outsider art project, an anthropological experiment, a surrealist game (directives asked watchers to note which items friends displayed in the middle of their mantelpieces) and a mass diary cataloguing prosaic fragments like a proto-blog. The written elements of MO have received the most exposure so far and this is the first in-depth survey of the sprawling archive’s photographs. Pioneering street photographer Humphrey Spender’s records of Bolton and Blackpool justifiably take centre stage. MO’s most diligent snapper-cum-snooper surveyed everything from pubs and football terraces to factories, shoppers, bowls pitches and funeral parades. At the other end of the spectrum, and at the opposite end of the gallery, are John Hinde’s staged and sun-bathed rural scenes (his later portraits of circus life are far more nuanced). Spender delighted in graffiti just as Brassaï was discovering it in Paris, while his interest in street signage (along with fellow MO photographer Charles Trevelyan) and covert methods echo those of Walker Evans who was also chronicling street life in the 1930s with his camera tucked under his coat. One particularly subversive display of Spender’s images questions such methods and exposes his outsider, upper-middle-class gaze: “The truth would be revealed only when people were not aware of being photographed … I had to be invisible” reads his statement on the wall, while next to it a man waving and a woman staring testily into the lens show him as anything but. Meanwhile vitrines are packed with contextual material to get lost in: innovative book cover designs; a handwritten report from Spender detailing an altercation with a pub landlord over photographing his customers; maps of Mrs X’s washing activities and exhaustive accounts of observers trailing subjects (“she scratches her right buttock with her right hand”); the biographical details submitted by MO’s many volunteers with their styled self-portraits like early Facebook profiles. Attitudes towards photography and art are probed through the organisation’s many surveys, while the records of MO’s art-appreciation groups for miners in County Durham – teaching materials as well as photographs of the miners’ own painted street scenes – stand out as a rare occasion when MO had direct and prolonged engagement with its subjects. The last part of the show concentrates on the second phase of MO from 1981 to the present day and takes us into the homes and minds of people (places where Spender and Co were never truly welcome). The limitations of such an experiment – that it is always a partial and subjective history – are clear to see: few of the middle-aged to elderly volunteers mention digital image-making in a survey of photography. Most arresting is a selection of photographs distilled from 55,000 contributions from one day in 1987. Here, grand, humdrum, strange and beautiful sights all sit side by side. Meanwhile in another entry on wedding presents, one anonymous retired radiographer annotates intricately assembled photographs of all the gifts she received in 1953 (“One for the bottom drawer,” she comments on a tablecloth). I hope that volunteer d2589 has come to see her still lives lining the gallery’s walls.

From British Circus Life, by John Hinde, 1948 (image: National Media Museum)

From Exmoor Village, by John Hinde, 1947 (image: National Media Museum) |

Words Isabel Stevens

Mass Observation: This Is Your Photo, The Photographers’ Gallery, London |

|

|

||