|

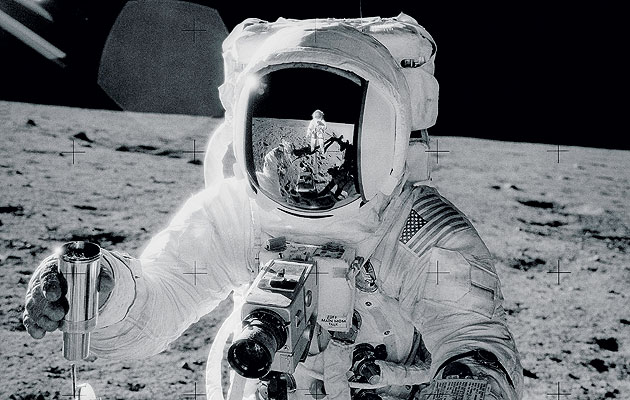

Alan Bean collecting soil samples on the Apollo 12 mission, 1969 (image: NASA) |

||

|

The US space programme was so expensive that Nasa made the cost a selling point – turning it into the ultimate luxury product, says Thomas Jones “Without public relations,” Wernher von Braun told the journalists assembled at Nasa’s Manned Spacecraft Center on 22 July 1969, as the Apollo 11 mission was returning to Earth, “we would have been unable to do it.” Von Braun, the director of Nasa’s Marshall Spaceflight Center, knew a thing or two about public relations, having successfully sloughed off his past as the Nazis’ chief rocket scientist and rebranded himself, in David Meerman Scott and Richard Jurek’s words, as “one of the greatest media stars of the space age”. Scott and Jurek are marketing professionals and amateur space enthusiasts (Scott “is thought to be the only person in the world with a lunar module descent engine thrust chamber in his living room”; Jurek is the proud owner of “the world’s largest collection of $2 bills that have flown in space”). Marketing the Moon is both a book about spaceships and “a singular and eminently instructive case study for modern-day practitioners” of marketing and PR. Scott and Jurek are using space travel, a subject which has instant mass appeal, to sell a book about marketing, which hasn’t. You might think the Moon didn’t need much marketing – next up, How to Sell Hot Cakes – but one of the reasons stories about space exploration are so popular, Scott and Jurek suggest, is that the people responsible for marketing the Apollo programme did such a thorough job, from Von Braun’s appearances on Walt Disney’s TV show in the 1950s, to astronauts’ post-mission roadshows around America, to the 100-page Apollo Spacecraft News Reference manuals that Nasa distributed to journalists. “Covering the space program presented a challenge to us all,” Walter Cronkite said. “There was a great deal we had to learn about the mechanics of space flight.” It wasn’t simply a case of getting people excited by the idea of sending men to the Moon (and they were all men; the United States didn’t send a woman into space until 1983). It was also a question of maintaining that interest – and, not unrelated but even more important, Congressional funding – for the best part of a decade. President Kennedy announced the plan to Congress in May 1961, more than eight years before it was realised. “No single space project,” he said, “will be so difficult or expensive to accomplish.” It was canny of the administration to make the expense a selling point up front, rather than try to play it down. In the second half of the 1960s, 4 per cent of the US budget went to Nasa (not including Department of Defense spending). Nasa’s commercial partners cashed in on the romance of manned space flight to sell their more mundane products back on Earth: Scott and Jurek reproduce adverts for Tang (“the powdered drink mix from General Foods”), Omega watches, Sony tape recorders, Ford, United Airlines, Union Carbide, Boeing, Panasonic, all trading on their connections to the Apollo missions. The ads benefited the programme, too, keeping it in the public eye. And Nasa’s relationship with the press was also symbiotic: “If we continued to help the space agency get its appropriations from Congress,” Don Hewitt of CBS News wrote in 2001, “they would in turn give us, free of charge, the most spectacular television shows anyone had ever seen.” In July 1969, 94 per cent of American televisions were tuned to the coverage of the Moon landings. Three years later, in December 1972, many fewer were watching men leaving the Moon’s surface for the last time. “A general mood of complacency, if not fatigue, regarding the Apollo program could be heard throughout the country,” Scott and Jurek write. One of the reasons for the declining enthusiasm (though only one) is connected to a photograph that Bill Anders took of the Earth rising over the Moon’s surface from Apollo 8, on 24 December 1968. The picture became an icon for the environmental movement, a spur to the dawning anxiety that the process of industrial development which had taken men to the Moon might end up costing the Earth. Marketing the Moon: The Selling of the Apollo Lunar Program by David Meerman, Scott and Richard Jurek, MIT, £27.95

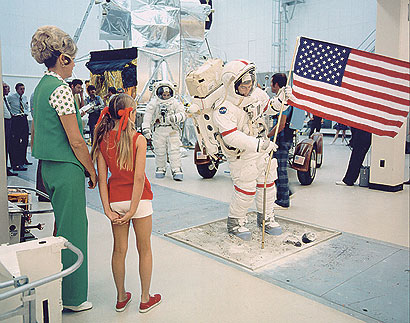

Eugene Cernan during training for the Apollo 17 mission, 1972 (image: NASA) |

Words Thomas Jones |

|

|

||